"BANJO" PATERSON ENDS HIS STORY. - PART 5

POLITICAL GIANTS AND

"PILGRIM FATHERS."

New Hebrides Venture.

A MAGNIFICENT FAILURE.

BY A. B. ("BANJO") PATERSON.

Written in 1939.

In this casual chronicle it is impossible to give more than a sort of thumbnail sketch of some celebrities who strutted their hour upon the stage. Plutarch, in his "Lives," did not disdain personal details; in fact, it was the details which made the "Lives" such a success. Here goes, then, to follow far behind Plutarch's tracks, deeply imprinted as they are in the soil of time.

With whom shall we begin? Sir Henry Parkes and Sir John Robertson stand out like lighthouses of the past. It so happened that I came in personal contact with these two great men, getting a sort of worm's eye view of them, and of their activities.

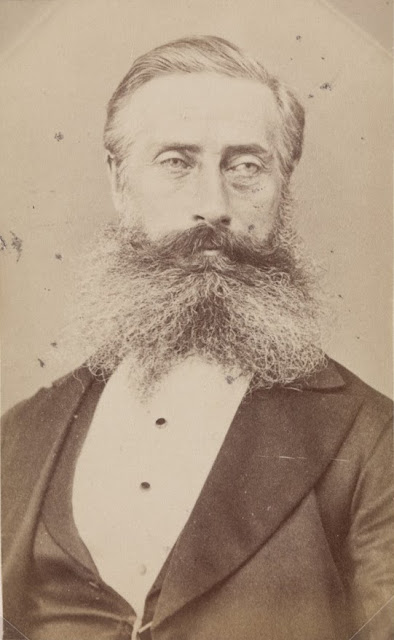

Sir Henry Parkes, with his mane of silvery hair and his Nestorian beard, adopted the role of the aloof potentate; in the argot of the prize-ring, he let the other fellow do the loading, and then countered him heavily. It is said that a field-marshal in war cannot afford to have any friends, and Parkes was a field-marshal, plus. Not but what he could relax on occasion, but always in an aloof, Jupiterish sort of way. I remember seeing him at a public dinner when the waiter poured him out a glass of champagne from a full bottle, and then moved off with it.

|

| The Hon. Sir Henry Parkes, G.C.M.G., May 1872 |

"Leave that bottle," said the statesman, who always got the temperance vote. "I'll finish that and probably another one after it." The old man never had any money, though goodness knows he had opportunities enough of getting it "on the side" had he been so minded. On various occasions he came into the lawyer's office where I was employed, always full of dignity, in a frock coat and a tall hat, to discuss his pecuniary complications. But personal finance bored him. He despised money; he was Sir Henry Parkes.

Sir John Robertson was also silver-haired and Nestorian-bearded but he was by nature what the Americans call a "mixer," prone to sit for hours in clubs or pubs entertaining his cronies; in fact, anybody could be his crony who was found linguistically worthy. He, too had a rough ride over the financial rocks.

In the gloomy days just before the banks shut I was told by one of them to write Sir John what the bank called "a nice firm letter" requesting the payment of some money. The old man came in, ran his eye over the office and asked, through his nose: "Who's looking after the affairs of this English, Scottish, Continental, Japanese, Australian . . . Bank?"

I said that I was.

"Well, you tell them not to write me any more d—d silly letters," and with that he went off to the club.

The bank asked what reply Sir John had made to the nice firm letter, and I said that he had given a nice firm answer.

Solidity Preferred.

Then there was Jim MacGowan who was (I think) the first Labour Premier — a serious-minded man, a Sunday school teacher, and with enough personal magnetism to hold his inexperienced team together.

|

| James McGowan (McGowen), Premier |

The Labour people in those days preferred solid leaders like MacGowan and J. C. Watson (who had been an "Evening News" compositor) to the Dantons and Robespierres and fiery Ruperts of debate. Not but what some of them had their human side. Donald MacDonell, a shearer, after whom MacDonell House is named, came back from an election campaign so hoarse that he could hardly speak. I asked him how the election was going.

He put his mouth close to my ear, and I thought I was going to hear some important political secret.

"Never mind the (adjective) election," he cloaked, "what's going to win the Doncaster?"

I think, if I may say so, that there was a lighter touch, more of the rapier and less of the bludgeon about political controversy in those days.

When Graham Berry, Premier of Victoria, appointed himself a delegate to the Home Office to get some amendment of the Constitution, did his enemies assail him with vituperation? Not at all. They hired a Yarra bank orator, a black man, to whose surname of "Henderson" they added the affix "Africanus" to give him some dignity — and sent him home in the same ship with Graham Berry to burlesque the show ! Unfortunately, "Henderson Africanus" was blocked somewhere in America, and London missed an historical comedy, if there is such a thing. A pity, too, for it was said of "Henderson Africanus" that he could talk the hind leg off a horse.

|

| Sir Graham Berry, Premier of Victoria, 1870 |

Sir George Reid and Sir Edmund Barton were latter-day successors to Parkes and Robertson — Barton all strength and solidity; Reid all repartee and tu quoque.

I saw Reid as a comparatively young man addressing a temperance meeting on behalf of the publicans, pleading for fail play. The temperance people, of course, gave him the "raspberry" and other unseemly noises with some spirited hissing. In a moment of quiet he said: "I came here to answer your arguments, but all I can hear is the ginger-beer bubbling in your brains."

With all his readiness in speech he was slow to come to a decision. When the kanaka question came up for settlement one way or the other, kanaka or no kanaka, Barton declared himself against the kanakas, but in favour of giving the sugar-growers time to get rid of them. It so happened that I went up in the train with Sir George Reid when he had to declare his policy in Brisbane. There were other Pressmen on the train, and in the intervals of sleeping and eating lollies he put us through a cross examination as to the views of our editors on sugar. After a while the senior reporter drew me aside and said: "You'll hardly believe it, but George doesn't know what he is going to say." Sure enough, in his speech he refused to give any decision, but said that he would go up and see the sugar country for himself.

With all his readiness in speech he was slow to come to a decision. When the kanaka question came up for settlement one way or the other, kanaka or no kanaka, Barton declared himself against the kanakas, but in favour of giving the sugar-growers time to get rid of them. It so happened that I went up in the train with Sir George Reid when he had to declare his policy in Brisbane. There were other Pressmen on the train, and in the intervals of sleeping and eating lollies he put us through a cross examination as to the views of our editors on sugar. After a while the senior reporter drew me aside and said: "You'll hardly believe it, but George doesn't know what he is going to say." Sure enough, in his speech he refused to give any decision, but said that he would go up and see the sugar country for himself.

This drew from some Bull of Bashan at the back a roar of, "Don't bother to do that George. They'll send the sugar to you in Sydney."

This qualified for first place in any "nasty remarks" competition; and Australia remained white when there was every indication of its going black.

I mention this because it was one of the crises of our history.

Reading and Writing.

As these are personal reminiscences I suppose I may be allowed to bore people with some of my experiences in reading and writing.

Looking over the shoulders of the young men of to-day, in trams, I find that they are mostly reading serious literature and high-brow stuff, while the elders are poring over love stories and sensational detective yarns, trying, perhaps, to recapture the past. The more things change the more they are the same. In our day, too, we young men read all the "improving" books we could get.

Henry George, an American compositor and apostle of the single tax, had a tremendous following, and when he came out to Australia we rolled up in thousands to hear him debate against a barrister named Rose. I can remember to this day the magnificent domed forehead of Henry George, gleaming under the gaslight. He was in deadly earnest, but his opponent had been platform grappling from boyhood, and threw punches from all sorts of unexpected directions — punches which disconcerted the philosopher.

Dropping Henry George, someone put me on to another hard one in Thomas Carlyle, and in Carlyle's "Past and Present" I thought I had found a workable formula for saving the world.

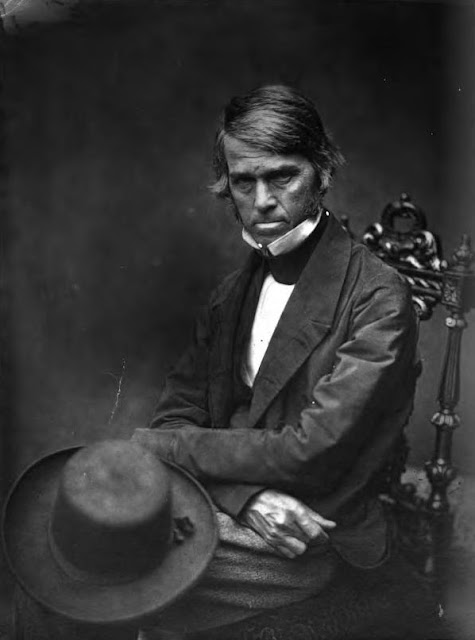

|

| Thomas Carlyle, from a Negative taken 31st July, 1854 |

Briefly put, his argument was that men are quite unfit to govern themselves, and that their only hope lies in finding the right leader. Experience later on inclined me to think that there might be something in his theory. Impressionable as I was at the time, I heard a big Government contractor say that if six hundred men were left leaderless on any job two hundred of them would go off after women, two hundred after strong drink, while the spiritless remainder would go on with the job! A very great man, this Carlyle, but there is a difficulty in convincing the world that it is unfit to govern itself. I read so much of his work that I can write fairly good Carlyle myself on occasion. For instance, how about this: "Consider man, insignificant insect, around him looms the universe, lurid, lit by lightnings; beneath him waits the Old Boy, expectant, disillusioned; and were man but worthy to know it, his destiny lies in the stars"?

Writing, too — what are we to say about writing ?

A man may have the luck to light on a line of his own — such as rough Australian verse — and get away with it. Failing this, the would-be writer has to go up against Shakespeare and Alexandre Dumas, which is like trying to take Gibraltar with a rowing boat.

Journalism, too, is like literature — everybody is at it. In certain universities they have schools of journalism; but without feeling particularly certain about anything I am inclined to think that the world will have little time for the machine-made journalist. The world wants the choice cuts in journalism, even though the butcher use his cleaver somewhat roughly.

For this reason I say nothing about wars, though I was in three of them as a spectator, and in one as an officer in the remount service.

The war is by now a ten-times-told tale, and there is little left to be said unless by a Lloyd George, who could have won the war in no time had it not been for the infernal Generals!

Apart from such studious activities, I once came very near being an Empire builder — if I had had any luck.

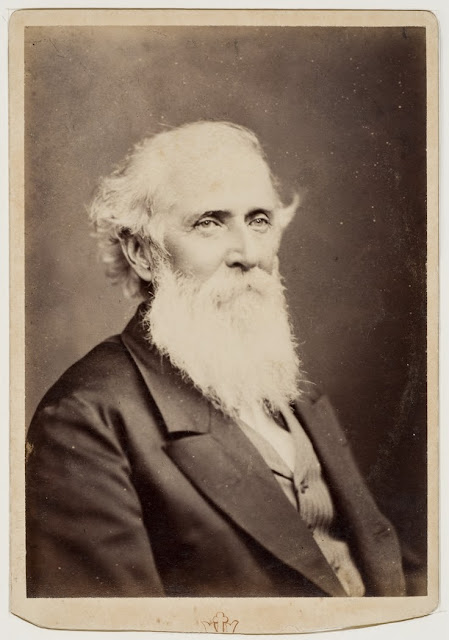

James Burns, or perhaps I had better give him his proper title, Colonel the Honourable Sir James Burns, of the firm of Burns, Philp and Co., was, at all events, as near to the Empire builder as we ever saw in these parts.

A thin and austere Scotsman of the old son-of-the-manse type, few people would have taken him for what he was — an outstanding financial genius. The great O'Sullivan might toss millions about with the abandon of an elephant throwing hay; but James Burns risked his company's money, and his own, in ventures which required a lot of pluck and a lot of foresight. They were merchants, ship-owners, island traders, and graziers; putting the firm's money behind settlers away up on the Queensland rivers where they were liable to be scuppered by blacks at any time; financing storekeepers in little one-pub towns, where these storekeepers found grubstakes for prospectors and miners; sending their vessels to the islands where no boat's crew dared land unless the bow-man had a loaded rifle; running small steamers to places where there were no wharves, and the boat just tied up alongside the bank. Anywhere that there was a risk to be run and money to be made you would see the flag of James Burns. If he had been dealing in diamonds, instead of copra and bananas, he might have been another Cecil Rhodes. I was sent by the "Sydney Morning Herald" to accompany a mob of Australian settlers which Sir James was sending to colonise the New Hebrides. A sort of Pilgrim Fathers affair, this, the settlers going down to live among wild savages in the land of the golden cocoanut. I found "Cecil Rhodes's" under-study in his office and he gave me the plan of operations.

|

| Sir James Burns, K.C.M.G., M.L.C. |

He said that his firm had bought thousands of acres in the New Hebrides. "Some," he said, "we bought from the old Scotch company which lost a lot of money in the islands and sold out to us; other areas we bought from native chiefs, traders, and so on. Now the French have gone down there, and we may have to fight for our land. The Scotch company areas should be all right as they were taken up and occupied before the French made any claim, but where we bought, say, a thousand acres from a native chief the French are now claiming that they bought the same land from the same chief or that they bought the same land from another chief who had a better right to it. Nothing can be settled till a Court is appointed to confirm the titles. We are sending these settlers down there so that, when a Court does sit we will have men on the spot in possession."

This promised some adventure.

The Argonauts.

Soon I was at sea with the Australian Pilgrim Fathers in search of the land of the golden cocoanut. This was not a bad ship, except that at some time or other she had tried to shift a coral reef and had got a sort of kink in her keel. The captain, a gigantic New Zealander, said she was inclined to steer a bit north by south unless carefully watched! "If you let her alone," he added, "she will go round and round in circles; but she's quite good enough for a trade where, any dark night, you might walk her right up on to a reef which has risen out of the sea since the last time you were along. There's a volcano on Ambrym — you'll see that — and I wouldn't be surprised, any night, to see fire and a new island coming up out of the sea. We've got the missionaries on board; it's their synod trip. They're good, well-meaning chaps, nearly all doctors, who do a lot for the niggers."

"Are the niggers dangerous?"

"They were until they got rifles. They could not hit a barn with a rifle if you put 'em inside it. If they want to kill a man they hide in the jungle and knock him with a waddy."

I made friends with the settlers and found they were the genuine article — hard-handed, anxious-faced men, miners, farmers, shearers, mechanics — all off to tackle a job of which they knew little in a land of which they knew less. Many of them were born adventurers who would start off anywhere at the drop of a hat, just for the sake of seeing something new. I fancy there must have been some of this sort with the original American Pilgrim Fathers.

|

| Kingston Jetty, Norfolk Island, c. 1880-5 |

Leaving Lord Howe we hit the real tropics and began to have adventure. A lady passenger came aboard at Norfolk Island and went almost straight to the ladies' bathroom. The ship had been fumigated for cockroaches before leaving Sydney, and the cockroaches, opposing instinct to science, had crawled into the tap of the bath. When she turned on the water she got a stream of cockroaches, all in the highest health and spirits. They fled in various directions, drying their whiskers as they went. It was just a first taste of the tropics, a prelude to the performances of the tree-climbing crab and the cocoanut-eating rat, the lawyer vine, and the stinging tree. Here, too, the Pilgrim Fathers got the first taste of what was ahead of them. They hired horses and went riding inland, where they saw Norfolk Island pines, and loquats, and bananas, and oranges, growing wild. Round the homesteads they saw kumeras (yams), sweet potatoes, coffee, fowls, ducks, pigeons, pigs, and cattle.

Our settlers had a sort of Parliament in perpetual session, comparing notes and experiences, quoting from pamphlets and political reports, in none of which they had any faith. Someone mentioned the humidity of the climate, which brought forward a man who had been sleeper-cutting on the Johnstone

River.

"I ain't afraid of the humidity," he said. "I stood the Johnstone River for two years. We used to wrap our matches in flannel and put them in a little bottle. Then we'd wrap that bottle in flannel and put it in a pickle bottle. Then we'd put the pickle bottle inside our coats, and then the matches would be wet. Bring on your humidity!"

What in the end stopped the development of the scheme? Simply that the French and English Governments waited to see what would turn up before authorising any decision about the land. Some of the settlers went on with their work but were met with tariffs, while their French neighbours were encouraged with bonuses! That was the end of a glorious undertaking.

"Banjo" Paterson Tells His Own Story

Sources:

- "Banjo" Paterson Tells His Own Story - V. Political Giants and "Pilgrim Fathers" (1939, March 4). The Sydney Morning Herald (NSW : 1842 - 1954), p. 21.

- Andrew Barton (Banjo) Paterson c. 1890; Photographer: Falk, Sydney; Courtesy: Mitchell Library, State Library of New South Wales

- The Hon. Sir Henry Parkes, G.C.M.G., May 1872; Courtesy: Mitchell Library, State Library of New South Wales

- Sir John Robertson, between 1875-1894 / photographer J. Hubert Newman; Courtesy: State Library of New South Wales

- James McGowan, Premier; Courtesy: State Library of New South Wales

- Sir Graham Berry, Premier of Victoria, 1870; Courtesy: State Library Victoria

- Thomas Carlyle, from a Negative taken 31st July, 1854; Past and Present; Courtesy Archive Org.

- Sir James Burns, K.C.M.G., M.L.C., (1917, June 13). Sydney Mail (NSW : 1912 - 1938), p. 33.

- Kingston Jetty, Norfolk Island, c. 1880-5; Courtesy State Library Victoria

No comments