❈ ❈ ❈ ❈ ❈ ❈ ❈ ❈

WILLIAMS AND FLANAGAN.

Williams and Flanagan were old Van Demonian convicts. They were drawn to Port Phillip, or Victoria, as it was then being called in official circles, by the gold discovery, but, being averse to dig themselves and no doubt ashamed to beg, they sought to make an easy living by taking what others had earned. Their impudence and daring were conspicuously exemplified by a series of highway robberies on the St. Kilda Road.

On a Saturday afternoon, the 16th October, 1852, in the clear light of a bright summer day, these two bushrangers kept possession of this important thoroughfare for about two hours and a half, sticking up every passenger who appeared. About thirty victims were secured, and robbed of everything of value.

The modus operandi was described by Mr. William Keel and Mr. Wm. Robinson, two of the gentlemen robbed. As they were driving along the road from Melbourne towards Brighton, where they resided, they observed two men some distance in front, carrying guns and occasionally looking up into the trees on the roadside, as if in search of birds. As Messrs. Keel and Robinson came up, however, they walked into the middle of the road and presented their muskets, calling out, "Keep still, or we will blow your brains out." This was supposed to be a joke, so little was such a rencontre anticipated in such a locality; but it was soon found to be serious earnest. The gentlemen were unarmed, and could not resist; they were at once compelled to drive off the road into the bush, where they could not be seen by passers by. Here they were required to hand over their money, which they did to the amount of £23 and £46 respectively. They were then taken into a piece of scrub, tied together, hand to hand, with part of a hempen halter cut for the purpose, and ordered to sit down. They found themselves in the company of a number of other unfortunates, watched over by two armed confederates, who were ready to fire on the prisoners, should they make the slightest movement.

"Keep them close together," said one of the desperadoes, "so that, when you fire, if you miss one, you'll hit another."

The men who had robbed Messrs. Keel and Robinson then went back to the road, but made frequent returns to the scrub with new victims. Among these were Mr. and Mrs. Bawtree, Mr. Larman. Mr. Striker, and other well-known and wealthy colonists. A gentleman of the name of Moody was the only passenger that escaped the bushrangers while they held control of the thoroughfare. The two robbers were at some distance from Mr. Moody, when they called on him to stop, but instead of doing so he clapped spurs to his horse and galloped off. Two shots were ineffectually fired after him. Mr. and Mrs. Bawtree were subjected to the rudest treatment, the villains, although remonstrated with, continuing to use the most abominable language, undeterred by the presence of the lady, whose pockets they insisted on searching. They were doubtless a little aggravated on finding that Mr. Bawtree carried no money with him.

Soon after Mr. Moody's escape the four bushrangers, probably fearing that he might raise a "hue and cry", mounted their horses, which were in the scrub; and their victims soon after left the scene of their imprisonment. Before information reached the authorities, the robbers had made good their retreat. The Melbourne detectives were, however, well up to their work, and succeeded where the ordinary troopers failed. We may let one of them tell his own tale:–

As the bushrangers had made no attempt to disguise their appearance we got a full description of their personnel, which I could identify as that of some well known old hands, distinguished by all the audacity necessary for such an exploit. We learned a day or two after the St. Kilda Road affair that four bushrangers, who had been practising their profession at Bacchus Marsh, had been seen in that locality by a trooper, and their description corresponded with that of the heroes of the 16th October. A little later we got information of four diggers, on their way from Bendigo to Melbourne, being robbed at Aitken's Gap by what seemed to be the same band of bushrangers. One of them was relieved of four nuggets and £23, and another, named Whelan, was, among other things, deprived of a pistol which he carried.

As they had enjoyed a successful campaign, we began to anticipate the early appearance of the robbers in Melbourne, where they might, through their ill-gotten gain, enjoy for a time the sweets of dissipation, or, more probably, attempt to ship for some other locality, as their victims in Victoria were too numerous to render their continued residence in this colony prudent or advisable. The usual precautions, which I have already described, in connection with other cases, were taken to secure the arrest of the men by watching the approaches to the city. In town, I and others did not despair of finding them, perhaps on our ground, and as anticipated, two of the men dropped into our hands as a party of us were, according to our wont at that lawless period, patrolling the streets at night. A little after midnight, while we were in Flinders lane, we observed two horsemen approaching—a suspicious circumstance at such an hour in that locality—we resolved to accost them, and got them to stop by asking a question on some irrelevant and unimportant subject, when we got up close to them. Their appearance, if not incompatible with innocent pursuits, was such as usually distinguishes the criminal; I could recognise the one I stood beside as an old convict; their answers to our questions were suspiciously evasive—they were evidently impatient of delay. In short, we felt assured that they would not suffer much from being overhauled at the watchhouse, and accordingly at an understood signal, acting simultaneously, we hurled them from their saddles, and, in an instant, they were handcuffed and secured.

When taken to the watchhouse, their effects made rather a respectable appearance. One of them, Thomas Williams, had £55 in sovereigns and notes, a nugget, a bundle of clothes and a pair of fowls, with which the unlucky rascals had probably anticipated making a comfortable supper, but they were destined to feed a more honest man, for the detective who searched Williams afterwards under cross-examination, amid the laughter of the court, said he had consumed the poultry, and that "they were very good". On the other man, John Flanagan, we found £47 10s. Each had a pair of heavily loaded pistols, which convinced us that the precautions we used in securing our prisoners were not unnecessary. One of the pistols was identified by Whelan as his property.

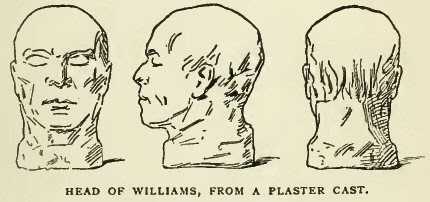

Both men were sworn to as being two of the four St. Kilda Road robbers by several of the gentlemen who had fallen victims to their audacity. They were likewise identified as the men who had robbed Aitken's Gap. They were found guilty, and each received three cumulative sentences, which, in all, amounted to thirty years' hard labour on the roads, a considerable portion of the time in irons. Both were old convicts who had been sent to Van Diemen's Land from England during the transportation era. Even in durance, the "wicked" Williams would not "cease from troubling" but took a prominent part in the murder of Mr. Price, for which he was executed, and it is to be hoped that he is "now at peace."

Of the fate of their companions in the St. Kilda Road bushranging, I remember nothing; but, probably, they were soon brought "before their betters" for some other crime.

Source: The Bushrangers (1915, April 16). The Farmer and Settler (Sydney, NSW : 1906 - 1955), p. 5.

No comments