It will be readily understood that the free portion of the population who lived in the invaded districts were greatly harassed by the marauders, whether they remained in their own homes or went on journeys. But they were not the only persons to suffer, for indirectly all travellers were made to share in the unrest and deprivations consequent upon the outrages of the convict freebooters; and their sufferings in some cases were caused by the overzeal of the authorities. On this point I will let a gentleman speak who had a large acquaintance with colonial life in those days. Mr. Harris, author of that remarkable book (now very difficult to obtain) "Settlers and Convicts", narrates some of the troubles through which he and other free immigrants had to pass in those unsettled times. He says:–

About three miles beyond Windsor, towards Sydney, we came to a group of constables, all armed and gathered round a young man, who evidently, by his English dress, had not been long in the colony. This of course they could see as well as I could, and as there was not the slightest indication in any other point of his being a bushranger, there was in fairness and common sense no ground for supposing him anything else than a free emigrant. They, however, insisted that, as he had "no protection", they would take him into custody to be sent to Hyde Park Barracks, Sydney, the head office "for identification". It was in vain that he remonstrated; their resolution remained unshaken. The chief constable of the Windsor bench was at the head of the party, and as he knew me well by often seeing me at Mr.———'s, he asked me no questions; otherwise I suppose I should have shared the same fate. They marched the poor fellow to Parramatta gaol that night, and next morning as my fellow-traveller and myself walked leisurely on between Parramatta and Sydney, one of the constables of the former town overtook us, having him in charge for lodgment at the Sydney police-office. As we walked on together I had a long conversation with him, and with my little discrimination in such matters, was soon quite sure that his tale was a true one. He had come out to the colony to an old friend of the family who had emigrated some years before to hold a respectable public situation, but on arrival found him to be dead. After trying to get employment till everything was gone but the clothing he stood in, he had wandered on up the road toward the interior, more from the impulse of hope than of any precise expectation, and had his journey cut short in the way described.

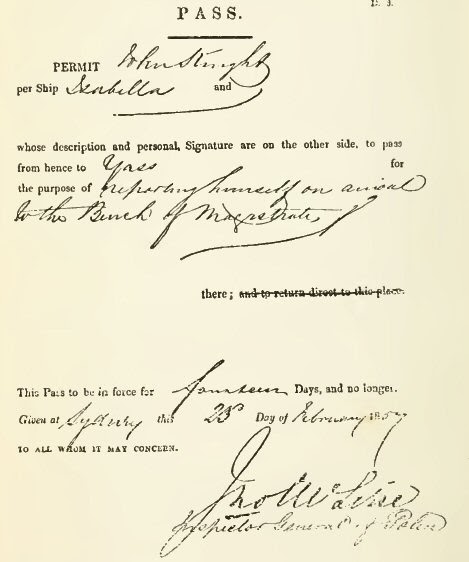

I felt curious to know how the magistrates would deal with the case, for to me it seemed a most flagrant outrage, whilst the constables maintained it was quite legal, and in the common course of things. I had heard of such things before, but did not quite credit them. I also felt interested in the poor fellow, for I recollected how my own heart had often sunk on my first arrival, when I tried day after day to get a job without succeeding. The magistrate, Captain Rossi, long the chief superintendent of the Sydney police, sent him to the prisoners' barracks, where the documents descriptive o' all individual transports are kept, but he was returned from thence as unknown. He was next sent to where he himself said he was known in town, and where it seemed to me he might have been better sent first; from thence he was brought back by a constable, with the merchant's certificate that he had come out a free emigrant to the colony a few months previously, in a ship consigned to his house. Captain Rossi then informed him that he was discharged. The young man asked what must he do if he was again taken into custody. Captain Rossi said he should then know him again himself, and would at once liberate him. The young man said this was not what he meant; suppose he were arrested again, many miles from Sydney, what was he to do? Could not Captain Rossi give him a "pass" to protect him as he knew him to be free? Captain Rossi said no, that was beyond his province; he would recommend the young man to apply to the Colonial Secretary. The poor fellow was about to reply, when a couple of constables had him turned round, marched out, and set at liberty at the courthouse door, before one could count half-a-dozen. I confess I was puzzled to credit the honesty of referring a man in immediate necessity of such an urgent kind to an official whose aid it would certainly require several weeks to obtain, especially as the poor fellow had no home for communications to be addressed to; and I was equally puzzled to detect the difference between the manner in which this son of misfortune had been treated under the magistrate's eye with his tacit consent, and a common assault, that it was the magistrate's duty to take cognizance of judicially.

After this affair I began to think myself very fortunate in never yet having met with the same treatment; which was no doubt owing partly to accident, and partly to my having always gone well dressed. Previously to this I had seen portions of such cases, but this was the first I had had an opportunity of observing throughout. As I am very careful on so serious a point to state only what I am positive of, I shall pass over plenty more where again I merely saw portions of the affair, to go on to such as I can speak positively to throughout.

The next was in my journey, hereafter detailed, up the New Country. In passing through Stone-quarry I went into a hut, which turned out to be a constable's, to rest. A few minutes afterwards a middle-aged man stopped at the door, and calling the constable out, inquired if he knew the man who had just passed. The constable replied very deferentially that he did not; the horseman I afterwards found was one of the magistrates of the New Country travelling to Sydney. After designating the poor constable by several rather singular names, Mr. ordered him to "be off after the fellow and bring him back." Without any further directions as to what was to be done with the man, Mr. pulled his horse's head round and cantered off towards Sydney. The man was accordingly brought back and lodged in gaol, where, as it was Saturday, and the court of the district over for the day, he would certainly have to remain until Monday. Some years afterwards I happened to meet this old constable in a distant part of the colony, and after calling to mind with some difficulty where I had known him before, I asked him what the man had turned out to be; he said, a free emigrant. He had been brought before the Stone-quarry Bench on the Monday, and after having been detained several days for the reply of a gentleman in Campbelltown whom he referred to as knowing him and able to recognise him by his handwriting he was discharged, but just as in the other case I have related, without anything to protect him against the repetition of a similar outrage by some other constable the very next day.

I come to a much later period of my residence in the colony for a case: not that no intermediate ones present themselves, but to show that only so lately as within the last four or five years [* This was written in 1846] matters were becoming much worse on this point, instead of better, as one would suppose should be the case as the free population came to outnumber in immense proportion the bond. In travelling through the upper part of the Hunter I stopped a few days at one of the principal farms. During dinner the first day, the farm-constable arrested a traveller on suspicion of being a bushranger, and put him in confinement in a private lock-up, built on the farm. The man was kept there several days before any magistrate sat at the adjacent court to hear cases; and it then turned out that the man had worked for that gentleman some years before, and who recognised him and discharged him. The poor fellow said he had come free to the colony twelve or thirteen years before, and was generally arrested twice every year under the Bushranging Act. He had made application in one quarter and another for some protective document, till he was quite tired and had quite given it up. He had now made up his mind to it, and it did not affect him as it did at first. He slept the time away as well as he could, and was all the readier for work when he got out.

A native had once told me he had some time before passed seven weeks out of three months marching in handcuffs under the Bushranging Act. Having been born in the colony he had no protective document whatever. Some busy farm constable arrested him on suspicion of being a bushranger, at one of the farthest stations at Hunter's River, where he was looking for work. After being taken in handcuffs to Sydney, full 250 miles, and discharged, he went to the Murrumbidgee on the same errand, where he was again taken into custody by a soldier and forwarded in handcuffs to headquarters under the same law.

As to the practice of the mounted police (dragoons employed on the roads under the magistracy) of handcuffing men to their stirrup-iron and so making them march or rather run, it was at one time very common. I have several times heard it stated that it was at last discontinued through a trooper leaving his prisoner thus confined at a public-house door, while he went in to drink, and the horse, startled by something, dashed off and killed the man.

Whole shoals of men, both emigrant and freed, are daily passing to and fro from one police office to another "for identification."...The farm constables are prisoners of the Crown, actually serving their sentence, who have been authorised to act ostensibly for the purpose of convict restraint on the farm. But no one questions their right to arrest under the Bushranging Act; and now that the settlers have commenced building private lockups on their own farms this really becomes a very serious matter...Free men do not like being continually called upon by prisoner constables to "show their freedom" and emigrants very often have nothing to show, while at the same time their bare word will not go for a straw; and thus, after going a couple of hundred miles up the country for work, they may be marched back in handcuffs, and eventually turned adrift in Sydney without a penny in their pockets. At the same time, if it has been regularly done under "The Bushranging Act", there is no redress.

One of the worst points of the system still remains to be told: diminution of sentence is held out to prisoners as an incentive to the capture of bushrangers. Thus there is a direct premium to the convict farm constable to arrest all individuals he can affix any suspicion to by the most active ingenuity; for it will be hard if out of ten or a dozen cards there does not turn up one trump. Hence some of these fellows' entire occupation is going about peering after every labouring man they can get a sight of, and demanding his name, business and pass; in short, putting him through as rigid and often as lengthened an examination as would a justice of the peace if he were charged with theft. And as they often do this, whether by Government authority or not I cannot say, on some unfrequented bush road, with a horse pistol in hand, there is nothing that can be done but putting up with it.

Source: The Bushrangers (1915, March 23). The Farmer and Settler (Sydney, NSW : 1906 - 1955), p. 6.

No comments