|

| The King's School in 1911 |

The Oldest Grammar School in Australia

The King's School - History from 1832 to 1911

The following history is an extract from "The Jubilee History of Parramatta", published in 1911: -

THE KING'S SCHOOL is so well represented in the pages that follow that introduction would be unnecessary, if it were not for one or two things. One of these is the desirability of placing before readers some concrete facts regarding this "Oldest Grammar School in Australia."

For over two generations - well into the third - The King's School has been unobtrusively holding up the flag of education. And with this main object in view: "to make man, first, master of himself, and, secondly, master of the world in which he moves." The words just quoted were uttered long after The King's School was established, professedly in order that "increased facilities should be afforded for obtaining a useful and liberal education." Perhaps, these words sound small, as compared with the others. But they come to the same thing in the end. Wherever you find to-day an old King's School boy of the average type, you will be shaking hands with a man who is educated above the average, who is master of himself and of the world in which he moves. Not intellectually, always; but always morally and socially. The King's School boy of the normal type can hold his own in any society - except the lowest; and he can generally fight his way out of that.

And so, The King's School might well have been left to its own high reputation and to the eloquent tributes to its excellence which follow this introduction. But, as a mere matter of history, something must be said about the School, from a purely statistical point of view. Archdeacon (afterwards Bishop) Broughton. "Vice-President of the Committee of the Clergy and School Lands," was the father of a plan for the establishment of two schools for boys, one in Parramatta and the other in Sydney. The plan was submitted in 1830, but it was not until two years later that it was adopted in practice by the establishment of The King's School.

Archdeacon Broughton called the School, not after the King, as some have supposed, but after his old school in Canterbury, England. This is abundantly proved out of the Archdeacon's own mouth. He went to England in 1834, from which visit, by the way, he returned the first and last Bishop of Australia. Whilst in the old country he was present at a banquet given by the King's School Feast Society, numbering amongst his fellow guests such distinguished personages as Archbishop Howley, of Canterbury, and the great Duke of Wellington. In reply to the toast of his health, the Archdeacon is reported by the "Kentish Gazette" to have said that "he had been placed at the head of of Christianity in a country where education was unknown - he spoke of New South Wales; and it was part of his duty to attempt the removal of the difficulties produced by the lack of an establishment for inculcating religion and general knowledge. He succeeded in founding a public school on what he hoped was a satisfactory basis. He had given it the name of The King's School (cheers), and in doing so, he trusted that he had acted from the praiseworthy feeling of reverence and respect for the place of his own education (loud cheers). There was now he rejoiced to say, a King's School at the antipodes (repeated cheers). At the time he left it upwards of 70 scholars, chiefly boarders, the sons of the most respectable inhabitants of the colony, had been entered, and there was every prospect of its success and prosperity." This report was re-published in the London "Times" of September 25, 1835, a copy of which the present editor was permitted to see by the courtesy of Mr. Sydney G. Boydell, a grandson of the Bishop.

The First Headmaster

Thanks to Dr. Andrew Houison, one can speak about the School from its earliest days, from the masters' point of view. The Rev. W. B. Clarke, M.A., F.R.S - whose name recurs frequently in this History - was a master for some four years under the Rev. Robert Forrest, the first Headmaster. Mr. Forrest was not a graduate of a University, but was ordained from St. Bee's College, and the Lambeth degree of M.A. was afterwards conferred upon him. The school was opened on February 13, 1832, in a brick house in Lower George Street. And the first boys were: Andrew McDougal, Edwin Suttor, George Rouse, Joseph Thompson, James Walker, Charles Lockyer, boarders; and six day boys - Orr (2), Oakes (2), George Macarthur and John Watsford. James S. Hassall, grandson of Samuel Marsden, entered in April, 1832, and after the June Holidays there were 100 boys in attendance, amongst whom one distinguishes the names of Blaxland and Futter. The increase in numbers meant the enlargement of the accommodation, and accordingly a new schoolroom was built, and two adjoining cottages were rented for bedrooms. One of these boarding-houses - thus early was adopted the plan which the present Headmaster has perfected - was under the charge of "Jerry" Hatch, a tutor, and the other under the charge of Mr. (afterwards the Rev.) W. Woolls, who was to become a prominent personage in the infant community. It is Mr. Hassall himself who, recalling in later years the irreverent manner of boyhood, tells us about the "Jerry" of Mr. Hatch's appellation; just as he also handed down the fact that the first Headmaster of the The King's School rejoiced - or otherwise - in the nickname of "Old Bob." The foundation stone of the present building, on the old Cherry Tree Gardens, was laid in 1834 by Captain Westmacott, A.D.C. to the then Governor, Sir Richard Bourke, who has used all his influence to prevent the enterprise from being set going. Government subscribed £2000 to the cost, and, whilst the building was going up, it paid the rent of the temporary school (£80 a year), whilst boarders paid £28 a year and day boys from £6 to £10. It was not a very high charge, and "Old Bob" and his assistants gave the boys full value for their money, the school-hours in Mr. Hassall's time being from 7 a.m. to 9 p.m., with, presumably, a few intervals for meals and games.

Mr. Forrest and his boys moved into the new building in 1836, but unfortunately it was not long before the first Headmaster was obliged by ill-health to resign the position he adorned and in which he had done such capital work. In 1839, accordingly, he left Parramatta and took the living of Campbelltown and Narellan. But even here, in his enforced leisure, the born schoolmaster had to exercise his vocation, and accordingly we find six boys of 16 and 17 years of age added to his family - two Nortons, two Oxleys, G. F. Macarthur and Hassall. Before long, the Macarthurs presented him to the living of Camden.

Divided Control

Meanwhile things were going none too well with The King's School. On Mr. Forrest's resignation the headmastership was taken over by the Rev. James Troughton, his brother-in-law, also a St. Bee's man. As, however, the new chief was not competent to teach classics, the Bishop of Australia - for to this dignity Archdeacon Broughton had now been elevated - appointed the Rev. William Branthwaite Clarke, M.A. (Cambridge), to take the higher forms in that subject. Mr. Clarke had come out to Australia in 1839 — he was then 41 years old — mainly in search of health, and the Bishop gladly took advantage of the opportunity to strengthen the School, which was afforded by the opportune arrival of a man who had already distinguished himself as a litterateur and who had more than laid the foundations of his subsequent eminence as a geologist. A

good story is told of his first visit to Parramatta. The Bishop drove him up and dropped him at the School, with the inquiry: "Can I do anything for you in Sydney. Mr. Clarke.'" This was the first intimation he had received that his sphere of usefulness had been definitely fixed for him, and that he was to remain in Parramatta. He accepted the situation philosophically. "No, my lord," he replied, "there's nothing you can do for me: unless, indeed you can frank a clean shirt to me."' It was one of the privileges of high officers in those days that they had not to pay for the carriage of

letters and parcels — their mere signatures were sufficient postage. But this was too much for the Bishop of Australia. "No, Mr. Clarke," he said, "I think I can hardly do that"; and there is no evidence that, then or thereafter, he understood the delicate hint of unpreparedness which the victim of his rough and ready method of appointment intended to convey.

Naturally enough, the Troughton-Clarke control was not a success, and in 1841 the Rev. William West Simpson was appointed Head Master. Perhaps he was not in office long enough to make his mark, but, any way, it was a dangerous experiment to appoint to the control of a young public school a gentleman whose scholastic experience had been confined to the teaching of a private school in London, There was the further objection that Mr. Simpson's only title to academic distinction was a Lambeth .M.A. granted in recognition of a presumably learned, but now forgotten, translation of the "Constitutiones Societatis Jesu, Anno 1558." For all that, he was doing good work when his career as Headmaster was unromantically but effectively stopped by an outbreak of scarlet fever, which attacked him as well as a number of the boys, and which compelled him to resign his office.

The next Headmaster was the Rev. James Walker (1843-8), the first Oxford graduate to hold the position. Mr. Walker was not only a brilliant classical scholar — "one of the best classical scholars that ever came to the colony," writes the Rev. W. B. Clarke

to Dr. Houison — but he was also well known as a botanist, and he frequently wrote on his subject to the press of the day, affording much valuable information on poisonous plants. His sons — P. B. Walker, who attained a high position in the Telegraph Department; Critchett Walker, so long Principal Under-Secretary; and R. C. Walker, Librarian of the Public Library, Sydney — maintained worthily the distinction of their father's name. Apart from his work in the School. Mr. Walker was largely instrumental in the establishment of All Saints' Church, and he was much missed when he resigned the Headmastership in 1848 and became incumbent of St. Luke's, Liverpool.

The Rev. Robert Forrest stepped into the breach on Mr. Walker's retirement, and during the five years of his second headmastership (1848-1853), he did much to maintain and establish the reputation and usefulness of the School. His own health had, he thought, been restored, and he set to work with energy to develop the activities of the institution for which in its infancy he had done so much. Unhappily, the hopes entertained of his continuance in robust health were not to be fulfilled, and Mr.

Forrest — whose services to Parramatta are gracefully commemorated by the "Forrest Ward" of the Municipality — died a few months after his return to England on his resignation in 1853.

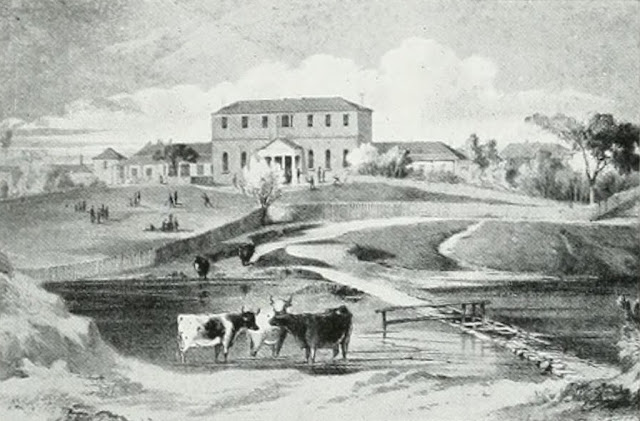

|

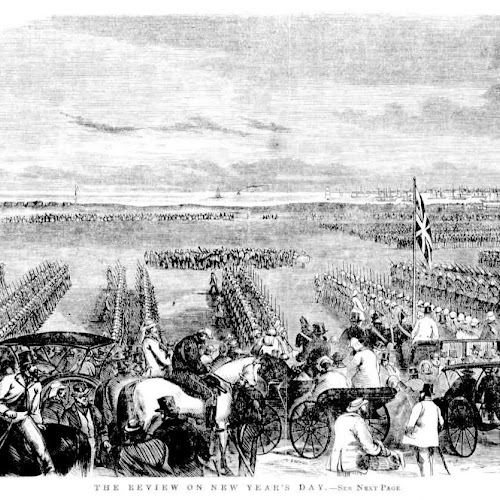

| The King's School in 1861 |

Mr. Forrest's retirement was but the beginning of the disasters which crowded on the School during the next thirteen years. Whilst the authorities were looking round for a suitable successor, the Rev. H. H. Bobart, M.A. (Oxford) — who had succeeded Samuel Marsden as incumbent of St. John's in 1838 — was prevailed upon to fill the gap. But it was too much for him, especially as, about this time, he was busily engaged in preparing plans for a new church to take the place of Marsden's building, which had been closed in 1852. He survived his appointment little over a year, dying at the School in June, 1854. A couple of months later the Rev. (afterwards Archdeacon) Thomas Druitt took charge, but he soon faded away from Parramatta and made room for the last Headmaster before the interregnum. This was the Rev. Frederick Armitage, M.A. (Oxford and Cambridge). An Oxford graduate in the first place, Mr. Armitage was a fine classical scholar, with French and German at his finger-tips; but what he did not know about mathematics would fill large volumes. Desirous of increasing his usefulness in this direction, he hit upon the strange scheme of going through the Arts course in Cambridge. But there was a difficulty in the way. Cambridge would gladly confer, for a consideration, an "adeundem" degree upon a graduate of the sister University; but it was unprecedented for such a graduate to enter as an undergraduate. Be that as it may, the unprecedented duly took place: Mr. Armitage matriculated at Cambridge, went through the Arts course and took his degree — not, however, in mathematics, but in classics! Good scholar as he was, and painstaking and earnest teacher, Mr. Armitage was deficient in the faculty of maintaining order and discipline, and, when he went to England on a twelve months' leave of absence, it was to bring from there his headmastership (1858-1866) to a close by resignation. Mr. L. J. Trollope, who took temporary charge during his leave, has recorded elsewhere the history of his valiant attempt.

But neither he nor any other man could have succeeded in the circumstances, and the Oldest Grammar School in Australia put up its shutters and remained closed.

Macarthur to the Rescue.

The interregnum lasted till January, 1869, when The King's School opened its doors again under the direction of the Rev. George F. Macarthur, himself an old King's School boy. For some twelve years before this, he had been successfully conducting a school at Macquarie Fields, and it was with his pupils there as a nucleus that he entered on the headmastership (1869-1886) which justified his claim to be regarded not only as the "Second Founder of The School," but as one of the greatest of Australian educationalists. Archdeacon Gunther — who did much to secure the re-opening of the School — has paid a fine tribute to the memory of this great schoolmaster, but there is yet material for a work, which should be of great interest, exclusively devoted to a study of his career, its lessons and its achievements. This material is mainly in private hands, and possibly will he used at some future date. For our purpose it must suffice to observe that Macarthur might have applied to his life-work the proud boast of Augustus — "I found Rome a mud village. I leave it a city of marble palaces." But with this difference: Macarthur ''found'' nothing — he made everything. He created the "tone" of The King's School, and he turned out every year the undoubted makings of manly men: the best type of Australians. The instruction imparted was simple and solid, and order and method were the watch-words of his just rule.

The high standard fixed by Macarthur was maintained by his successor, Rev. A. St. John Gray. M.A. (1886-8), who could truly say when he resigned his trust that "during his connection with the School he had always kept in mind the one great obligation laid upon him — to do his duty honestly and faithfully to the School and to the parents of the boys entrusted to his care, without at any time allowing private or personal considerations to interfere with his conscientious course of action." Mr. Gray's headmastership — abruptly terminated by the necessity of returning to England on the ground of Mrs. Gray's health — is chiefly memorable for the opening of the School Chapel, subscriptions towards which had been begun during his predecessor's reign.

The Last Twenty Years.

The Rev. Edward Harris, M.A.. D.D. (Oxford), brought with him from England — where he had filled important educational positions, including the Headmastership of Exeter School — a reputation for culture and scholarship and thoroughness which he brilliantly maintained at The King's School (1889-1895). During his term of office, it will be remembered, there began the "hard times" which had such an effect on New South Wales, and necessarily upon the School which is so largely recruited from the pastoralists and from all whose prosperity depends directly on "the land." This, of course, re-acted in various ways, but Dr. Harris could point when he resigned to various achievements of importance, and, above all, to the firmer and firmer establishment of the reputation of the School. "Our aim," he said, "has been to do the small things of daily duty as well as we could do them, and to do everything, be it work or be it play, well." The aim was fulfilled.

|

| The King's School in 1899 |

If Dr. Harris felt the beginnings of the bad times, his successor, the Rev. Arthur Hammerton Champion, M.A. (Cambridge), had all the rest of them during his term (1895-1906). Yet by dint of hard work and unfailing and sincere attention to duty, it could be said of Mr. Champion that from a total of 78 boys at the School when he took charge the numbers rose to 100 boarders and 47 day boys, and that considerable additions had to be made to the buildings. In the case of a man still living — to live, as we may hope, for many more years of usefulness — it is well to keep silence, yea, even from good words. But it may be permitted to transcribe here a sentence from the "Sydney Morning Herald" on the subject of his resignation: — "In his characteristically quiet and unostentatious manner, Mr. Champion did much to confirm the high reputation of the old School, and to advance the cause of sound education." A higher note was struck by the late Norman J. Gough in his appreciation: — "To be a gentleman in the face of things in general is not always easy, and, perhaps, for many of us Mr. Champion has made it easier, for his work has lain as much with humanity as with the humanities.... If Mr. Champion has never crammed a boy, he has never suffered one to go empty.... Here was the note of a great simplicity, of unaffected charm: here was a man who had power, but did not set it on a pedestal: who was simple, and yet added dignity to a position which was itself a dignity."

Now, for the second time in the history of the Oldest Grammar School in Australia, an Old Boy reigns in The King's School, and the fact prompts the wish and the belief that the Rev. Stacy Waddy, M.A. (Oxford), may be a second Macarthur in influence for good and in success of every kind. It would ill become us in a History to which Mr. Waddy has contributed some interesting pages, to speak more particularly of his work and his methods than he has himself cared to speak; but we may be permitted to mention a few facts and figures which speak for themselves. During the last 4 ½ years, the following additions have been made to the School buildings: — New dining hall, new library, museum, kitchens, etc., and the swimming bath. Three School houses — Broughton, Macarthur and Old Government House — have been established, thus providing accommodation for 184 boarders and 50 day-boys. This number, now in attendance, is easily the highest on record; and if the Council wants to receive more boys it will have to see about enlarging its increased borders.

Provenance: "The Jubilee History of Parramatta". In Commemoration of the First Half-Century of Municipal Government, 1861-1911. Edited by J. Cheyne Wharton.

Author: Edited by J. Cheyn Wharton

Date of Publication: 1911

Publisher: Thomas D. Little and Richard Stewart Richardson, The Cumberland Argus Printing Works

Place of Publishing: Parramatta, New South Wales

Copyright status: This work is out of copyright

Courtesy: University of California Libraries via the Archive Org.

No comments