WHAT I SAW IN THE ASYLUM.

The Tragedy and Humour — Revealed in a Day's Tour — Through the Claremont Hospital for the Insane.

(Special to " The Call.")

THE most frightful thing that can happen to a human is to be stricken with lunacy, yet it is a subject that the Man in the Street knows next to nothing about. As in the dreadful old days when people who had become "possessed of devils" were put to horrible deaths, the ordinary person still regards lunacy in the light of a sort of Bogey, and is ready to believe almost anything anyone likes to tell him concerning an Asylum.

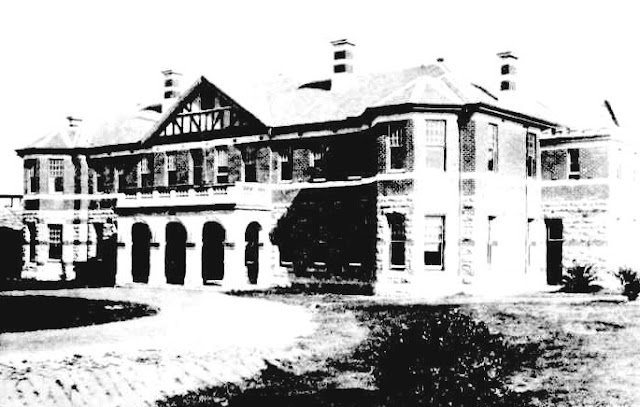

Memories of old-fashioned stories he has read of the horrors of the Madhouse spring readily to his mind, and his excited imagination often can't quite realise that a modern Asylum is (or is meant to be) a hospital for the treatment of the mentally sick — an institution for the care of those incapable of caring for themselves. The other day, in company with Canon M'Clemans, who has been connected with the institution as Anglican chaplain since its establishment, I made a tour of inspection through the Claremont Hospital for the Insane.

|

| The Administration Block |

Many Things — Expected and Unexpected.

I saw there many things I expected to see and some I did not.

From the red watch-house at the entrance gates there is a short driveway through neatly-kept lawns and gardens to the wide porch of the administration building. I was first taken through to the store, where, from a distance, a much-uniformed individual eyed us sternly. I was told he was the "Brigadier," and, further, that he was a patient with harmless ambitions running to startling effects in uniforms. These he was allowed to gratify, and he seemed quite happy in all his martial glory. A closer view, and I was startled to see that he was a Chinaman!

A bit further on an elderly gentleman was gravely occupied in pouring water from one bucket into another. He stood up as we approached, and raised his hat to us.

"Well," said the Canon, "have you been able to pick them all right lately?"

"Pick 'em!" he answered. "If I was out o' here I'd have every one of them bookies in the bankruptcy."

He laughed gleefully. "They can't beat me," he called after us as we made our way to the bake-house.

The Hospital bakery, kitchens and laundry are wonderfully up to date. Steam-cooking is the order throughout the institution, and the food I saw in preparation seemed to be of the best. A batch of bread just taken from the ovens would put a lot of city bakers out of business if it was sold in competition with them.

Padded Cells Out of Date.

The majority of the patients were out in the exercising yards, and I was conducted through a long series of clean, well-lighted and airy wards.

I saw only one padded cell, and it was explained to me that the modern treatment for a violent patient is not to chuck him out of the way to let him rave himself to exhaustion, but to put him into the care of one or more special attendants. If possible he is given a hot bath and then put to bed.

The violent patients are called "ticket" men, which means that the attendants on duty over them hold tickets for their unfortunate charges.

They must never be allowed out of sight, and the attendants are personally responsible for their welfare.

Followed our tour among the patients themselves in the exercise yards, and it is an experience, though some of the little happenings I will tell about may appear amusing, I won't forget in a hurry.

The awful fates of those helpless sufferers, abandoned more often than not by every friend and relative they may ever have had, is too tragic for mere words. In truth, some of them are said to be happy, and all seem to be not unkindly treated; but what untold torture must so many of them suffer in the frightful wanderings of their own twisted imaginations!

At every few steps we were met with pitiful pleas from obviously insane people that they were "all right" and were being unjustly detained in the Asylum.

The Canon's invariable promise (it was the only thing to say) that he would see the doctor on their behalf was met sometimes with slavish gratitude and sometimes with volleys of forceful abuse.

Often we heard bitter complaints about relatives who had promised to visit the unfortunates, some of whom had been waiting with growing misery for months for the promise to be fulfilled.

Quavered one old, old man: "They never come, they never come! And they swore before God they wouldn't forget me!"

A sun-browned person, with his hat fastened in some remarkable manner upside down on his head, crept stealthily up to us.

He drew us aside from the hearing of any other patients.

"D'you know that big gum tree over there?" he whispered hoarsely — "the one shaped like a blue horse?"

"Yes?" we said.

"There are seven dead bodies buried under it. And I put 'em there!"

And he crept away as stealthily as he came.

The Canon turned to talk with an ancient who had once been a minister of religion, and I suddenly found beside me the most despondent looking creature I have ever seen.

A straggly beard covered a wan face, and a pair of melancholy eyes peered out from sunken, watery sockets.

"You've heard people say they're as happy as Larry?" he asked in a hushed voice.

"Yes," I said.

He brushed a tired old hand across his eyes. "I'm Larry," he murmured.

THE BILLIONAIRE.

In the centre of the yard somebody was telling nobody in a loud voice all about his adventures "when 'e was a nipper knee-'igh, see?" The other patients took no notice of him whatever, and he didn't seem to mind thee absence of an audience, unless one forlorn individual who was tramping round in a small circle nearby with his arms held straight above his head could be called an audience.

We walked on a bit further, past a Hindoo who was twisting his fez round and round on the top of his head, by a young man who moved about on all fours. All nationalities were represented. Two Chinamen came up on either side of us and began to shriek in Chinese.

Nameless noises arose on all sides of us from gibbering tongues. Over by the gate a mindless man stood making dreadful sounds to the sky.

The glimpse I caught of a terribly distorted face has appeared before me since in nightmares.

At that moment the arrival of the Billionaire was a welcome diversion.

"I can give you that cheque for seven hundred and fifty million right away," he said to us.

We explained that we'd call back in a few moments about it.

"You'd better hurry," he cautioned. "I leave shortly on an extended trip to the moon. However, I will see that my secretary has the cheque drawn up ready for signature."

And he hurried away.

Another patient stepped up to us cautiously.

"He's mad," he said, pointing after the retreating Billionaire. "You want to be careful of him."

THE INEVITABLE.

We thanked him kindly and moved on to the Man in the Tent. He was one of several patients inclined to be consumptive, and was undergoing the fresh-air treatment. He glared at us somewhat hostilely from his tent until he was asked whether he'd been winning lately.

"Pretty fair," he said. "Picked the card last Saturday for a meeting in another country. If you see me soon I'll have the winners selected for the next three Melbourne Cups."

We went inside again and upstairs to the men's sick-bay.

A bombshell of abuse was thrown at us for no apparent reason by a bewhiskered man in the near corner of the ward. Further along at a table and beside a tremendous dictionary sat the Socialist. He stopped to explain the six principles of Socialism, which were the foundation of his new book "An Understanding of Socialism."

He talked lucidly and to the point, and showed a better grasp of his subject than a lot of people outside Asylums who write heavy volumes about it. The reason of his being in Claremont is a tendency to defy gravity from high places.

THE SCIENTIST'S QUEST.

The Scientist had a special little workshop fitted up for him where he could carry on his searchings after Perpetual Motion without hindrance.

It was a remarkable little place, littered with bits of carved wood, metal castings, drawings and paintings.

He said he was getting along slowly, and remarked that his difficulty was not so much to find Perpetual Motion but to find it in such a form as could be of commercial value.

Which hardly seems the statement of a raving lunatic. It was explained to me that there are many in the Asylum who have been practically cured but are allowed to stay on there for the simple reason that they would be hopelessly helpless if turned out into the world again to battle for a living. And the Scientist evidently was one of these.

We went along to see the women and child inmates, and the less I say about the sorrow I saw there the better. The kiddies seemed happy enough, though, singing in pitifully wandering voices while their teacher played for them at the piano. There were about thirty of them, and I was told they were all practically hopeless.

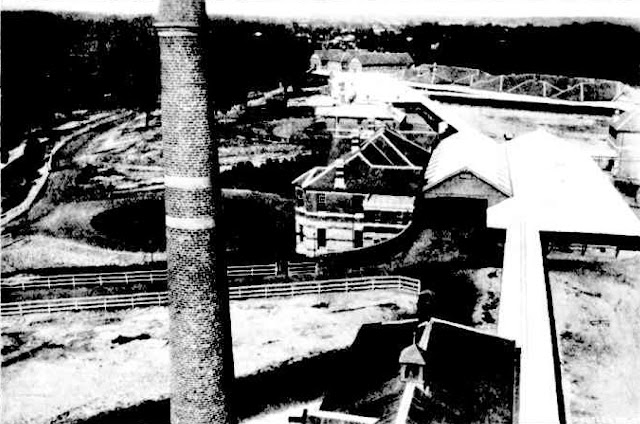

We tracked across the well-kept Asylum grounds to another part of the institution where another wardfull of patients was having dinner.

On the way we passed the dairy, fitted out in the most modern and hygienic manner, and the piggery.

The Asylum farm produces nearly £3000 a year for the Government and the piggery something between £800 and £1000, for none of which the institution gets much public credit on the Government balance-sheet.

A MOVEMENT TO ABOLISH FREEMASONRY!

The patients' dinner was a noisy ceremony. As soon as we entered the long room a little man rushed us and plunged into an immediate discussion with himself on chess problems, or some such abstract subject.

Another chap told us with gleeful delight that he was cute.

"Yes?" we said.

"I'm cute!" he said, "I'm cute!

They want to get me out of the Asylum, but I'm too cute. I won't let 'em!"

We walked down the room a bit and a chap stood up with a bit of paper in" his hand.

He said he was about to read a law he had framed for the abolition of the Masons.

I can't remember the extraordinary legal phraseology he employed — the there-ats and where-ins, the here-in-befores and what-so-evers. But it was to the original effect that Masonic Lodges were iniquitous because they used "wicked implements and instruments" against the general public for the prevention of the latter from picking winners at the races!

He therefore moved that "Parliament herein assembled at the Claremont Hospital for Insane whereat" should totally abolish the said Masons.

Even some of the patients smiled.

And so I come to the end of a plain, unvarnished account of all I saw and heard on my visit to the Claremont Hospital for the Insane, where of every hundred patients who enter forty are cured and discharged, and seven return. As far as I could see, the hospital is kept clean throughout, and there could hardly be any cause for hostile criticism on hygienic grounds.

As representative of "The Call" no door in the whole establishment was held closed to me. I had only to ask and it was opened, and I saw nothing to justify complaint.

There has been much said against the Asylum. Let what I have seen at least stand in its favour.

Geoffrey M Pacoby

Sources:

- What I Saw in the Asylum (1920, April 23). Call and WA Sportsman (Perth, WA : 1918 - 1920), p. 7.

- How the State Cares for the Afflicted in Mind — The Hospital for the Insane at Claremont (1912, August 24). Western Mail (Perth, WA : 1885 - 1954), p. 6 (ILLUSTRATED SECTION).

No comments