AN EXTRAORDINARY CONTRAST

GOULBURN GAOL

I. - AS IT APPEARS TO A VISITOR

The goal at Goulburn is one of the largest in the colony. It stands at the northern end of the town — the site of old Goulburn — and is surrounded by a fenced reserve. A few minutes' drive from the railway station takes the visitor to the massive gates of the establishment, which stand at the end of an avenue dividing the reserve. On either side of the avenue stands a handsome structure, which serve as the residences of the gaoler (Mr. Herbert) and his chief warder (Mr. Graham). Upon presenting his order for admission, the visitor is conducted by a warder to the office of Mr. Graham, who inspects the pass and then hands the visitor over to the care of a warder, to be shown around the gaol. It was originally intended that the institution should serve as a model or separate system establishment, but the influx of criminals was so great that the authorities had to work it as a gaol in which prisoners should finish, as well as begin, their sentence.

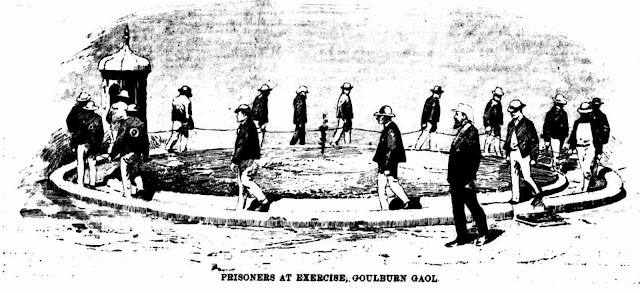

The separate system is worked as follow: — When a prisoner is sentenced to a term of three years or over he is compelled to spend the first nine months in separate confinement. He sleeps in a separate cell, and has no means of communication with his fellow-prisoners. He must remain in his cell during the whole of the time, save for one hour's exercise daily, for the first six months, and for two hours during the remaining three months. This exercise simply consists in walking around an asphalt ring, holding to a light chain with others who may be undergoing like treatment. He is allowed to work at his trade, if he has one; if not, he is generally employed at knitting socks for the use of the other inmates. His rations consist of four ounces of boiled meat, a quart of soup, half-pound of potatoes, 12 ounces of bread, and two plates of hominy daily. This food is only varied at Christmas and Easter, when it is somewhat augmented. All the prisoner under separate treatment are kept in D wing, in charge of warder Llewellyn.

Immediately in front of the gate stands a building used in turn by the Episcopalians, Roman Catholics, and Presbyterians as a church. It is fitted with gas, but the church is never open at night time, owing to the danger of revolts that might attend the mustering and marching of a body of prisoners after dark. The hospital also stands near the entrance, and it is a remarkably clean and airy establishment. There were about a dozen patients there on Saturday last.

The women's wing stands on the left of the gates, and there are about 90 prisoners there at present. They are chiefly employed in washing the clothes of the male prisoners, though the blankets and heavier materials are washed by a machine worked by men.

The stores and workshops stand to the right of the entrance. In the latter about 25 men are employed in tailoring, a dozen at bookbinding, 23 at shoe-making, and others at tinsmithing, carpentering, and blacksmithing. The clothes and boots used for Albury, Wagga, Mudgee, Trial Bay, and several other gaols are made here, and the work appears to be done in a very neat and complete manner. A record is kept of the work done, and prisoners who do more than the scale have a small monetary allowance made to them on leaving the gaol. A school house, embodying a library, is at the end of the workshops, and a bathroom is just across the yard, which the prisoners are compelled to patronise at least one day in the week— Saturday.

Prisoners who have been convicted more than once are kept together, and youths and others in for the first time are also in the one compartment. The most desperate of the prisoners are kept in little triangular yards partly roofed, each yard being occupied by one man. They are taken to their cells after dark, and are allowed to hold no communication with other prisoners. They are also kept in their cells on Saturday afternoons, when the other prisoners have a little relaxation.

The kitchen or cookhouse is a model of cleanliness — the tables a white and spotless as wood can be. The food used in the institution is all cooked and served up by prisoners under the charge of a first-class warder, and it was affirmed that rarely does a prisoner need to complain of the manner in which he gets his food prepared. Each of the seven yards in which the prisoners are divided is furnished with tables and stools. The prisoners are divided into messes, generally of six, and their dinners and hominy served to each mess in kits, which are afterward returned to the cook house, and thoroughly cleaned. The rations served are a follows:— A long timer, who has served 12 months or over, has a weekly indulgence of 1lb of sugar, and ¼lb tea, 1 ½ oz tobacco, and a box of matches per week. A pipe, instead of the box of matches, every fourth week.

The daily food is: — 7oz of cooked meat (boiled beef), without bone, 6oz of cooked potatoes. About a quart of good soup, plentifully supplied with vegetables, 1 ½ lbs of bread. Unlimited hominy, and an extra ounce daily of sugar to eat thereon. The boiled meat is agreeably alternated on Sundays by roast mutton, and on Wednesdays by roast beef. Those doing lesser sentences, one year or over nine months, are deprived of tobacco, matches, tea and sugar, have always to eat their meat boiled, and the ration is somewhat less in quantity. But the short-timer is not nearly so well off, his ration is smaller, and the drunks and petty criminals do not find their quarters so agreeable as to induce them to return. A man doing anything under six month has daily:— 2oz meat, 12oz bread (precarious and only allowed after the expiration of a month), and has to fill in on hominy without sugar. A pipe to him is a thing of the past, and the remembrance of his last chew, like the "baseless fabric of a dream."

The C wing is the dormitory for the prisoners. It contain 114 cells including two condemned, and several silent ones. Each cell is occupied by three prisoners, the law of this and all other gaols now being that either one or three prisoners must sleep in one apartment. Each cell is furnished with a hammock, rather narrow, being only the width of sailcloth, of which it is made, also two cocoa nut mattings on which the other two have to sleep. Each inmate is furnished with four blankets and two rugs in winter, one blanket less in the summer months.

At 4 o'clock hominy is served up, and at 5 the prisoners are mustered off to the cells; at 5.45 a.m. the first bell rings to rouse out, and an hour afterwards the cells are unlocked and the inmates once more go to the yards.

At 8 o'clock work commences, and is continued till 4, with an intermission of an hour from 12 to 1. Among the prisoners at present confined in Goulburn Gaol Is Colonel Brown, said to have been one of the heroes of the Balaclava charge. He is serving a short sentence for forgery, his employment being that of a clerk over the boot-makers. Berners, the late head clerk of the Railway Department, is also in the establishment, acting as school-master. There is also a desperate character, named Quinlan, who received a sentence of twenty years for attempting to murder a warder at Darlinghurst. He proved somewhat refractory in other gaols, but appears to be more contented with his lot in Goulburn. One of the bookbinders is a man sentenced for bushranging in Bargo Brush, but after finishing that term of imprisonment, he was convicted of another offence. The gaol is fitted with a gallows, but though the institution has been opened more than three years, no execution has yet taken place there. A prisoner named Rowlands, sentenced to death for a murder near Cootamundra, was awaiting execution at one time, but his sentence was commuted to a term of imprisonment before the fatal day arrived. There is room in the gaol for 700 prisoners, but only about 270 are confined there at present.

The impression left upon the mind of the visitor is that Goulburn Gaol is a well-conducted establishment, it cleanliness being somewhat remarkable, and reminding on of the well-scrubbed decks of a man-of-war. The unfortunates who are compelled to go through the monotony of prison life have all the comforts which are compatible with the idea of punishment; while at the same time a thorough system of discipline appears to prevail there — the whole arrangements reflecting credit upon the gaoler, and those who serve under him.

II.— AS IT APPEARS TO AN INMATE

How wise are our legislators; how beneficent our executive authorities; how magnanimous is the Comptroller-General's Department in providing for our surplus population on establishment where free board and lodgings, medical attendance — in fact all that the human race demands for its comfort, can be obtained at the expense of an over-taxed and deluded people.

Many and many times during the past few months have I heard men — strong, active, able-bodied men, — congratulating themselves that their time had fallen in pleasant places. The cry of distress of the unemployed has penetrated through the thick and high walls of the Goulburn Gaol, but has there found no responsive echo. There, all has been peace and contentment. Do the people know that in their midst there is a college in which crime is taught, its punishment laughed at? Where, from the moment an unfortunate criminal enter its precincts, he lives a life of ease and comfort. I don't know whether this gaol is the only place of the kind in this colony or not. But i can record what I know of Goalburn Gaol, and I leave it to the intelligence of my readers to say whether or not the other similar institutions are carried on in the same manner. Many time I have pitied the seemingly unfortunate men who have been sentenced to a term of imprisonment. That was long ago. Now they are to be viewed with the eye of envy. As a class, they live better, dress better, are cleaner, happier, and in all respects better off than any class outside the walls.

Let me select a day and follow it's routine of labour, and I was going to say pleasure,from the beginning. I will choose a Friday, for a prisoner, who, being sentenced to hard labour, has been consigned to the stone heap. At a quarter to six in the morning the first bell rings to wake him up; at a quarter past he rolls out of bed, arranges his blankets neatly, waits for his door to be opened, and goes to his yard, Here, by the time he has had a wash in a washstand and brushed his hair, blacked his boots, and made himself presentable, boiling water is brought round to him, and he makes his tea. He is then served with his hominy and bread, and sits down to enjoy, at his leisure, his breakfast. The bread is good; the hominy is good, and both are plentiful. A cart comes every morning and carries away a large cask of surplus food. Then he fills his pipe, discusses the news of the day — sometimes

with his fellow-prisoners, sometimes with the warders.

I saw in your paper [The Australian Star] recently an article in reference to the prisoner Holt, in which the fact of the outside news getting inside Darlinghurst was noticed. Before the prisoners in Goulburn Gaol went to their cells, at 3 o'clock on the day of the last Beach and Hanlan boat race, everyone (unless, possibly, the separate men) knew the result, even to the distance the race was won by; and early next morning the time in which it was rowed was a theme of interest. Nay, more, sweepstakes in tobacco and matches, books and handkerchiefs, were paid over to the winner; and soon every event. Horse handicaps, before any race meeting of importance, are matters of discussion and subjects of wagers. These various topics engage his attention till 8 o'clock, when the bell ring to go to muster, and afterwards work. He shoulders his stone-hammer, walks carelessly to the stone-yard. Stopping on the road to converse with various of his friends who are in other yards, picks out a pair of green goggled to protect his eyesight from the danger of particles of stone going there in, and finally settles himself down to his day's labour. He sits down and bits a stone with his hammer, not too hard, or it might break and necessitate his reaching for another. But perhaps figures may be more instructive than any other method of showing the work actually done.

In the latter part of September, all the broken stone was carted away, and a fresh start made, with on average of twenty men constantly breaking stone, the result of their labour was that in November, or two months afterwards, the enormous quantity of 30 odd yards — at any rate, the best of 40 yards had been broken — and at the present writing not more than 20 yards is lying broken — less than one square yard per month for each man. Outside, the price for breaking the same stone is 4s 6d per yard, and a man would have to break at least thirty times as much to keep himself from starving. Friday morning is shaving day, and the prisoner has to suffer the indignity of a clean shave. But by a merciful dispensation of providence all do not have to submit to this degradation. For if you have friends outside who will send in a petition for you, whilst that is in you may grow a beard till the answer is returned, favourably or otherwise. The department are in no hurry to answer these petitions, and you will see as heavily bearded men inside as out. Then three months before discharge one is allowed to "grow," so that a fair sprinkling of bearded faces is to be seen.

At half-past 9, the jailor and deputy make a tour of inspection. That's the last you see of the jailor that day — the rest of his time, the onerous duties of his office compel his undivided attention — the most onerous duty he has to fulfil is evidently the taking of photographic views of the gaol from every standpoint, at least that is the impression of the prisoners, for it has been whispered he was formerly a photographer, and he still has the ruling passion strong. At 12 o'clock — or rather quarter to 12 — an adjournment is in order for dinner. Here, likewise, the unfortunate criminal is well off, an abundance of beef, soup, and potatoes are his portion. After dinner he resumes his arduous labours till quarter to 4, and then he has a period of rest to recuperate his exhausted energies for the following day. At 5 o'clock he retires to his cell and there with conversation, reading, smoking, step-dancing, or gambling, wiles the fleeting hour away. Certainly, the song must not be too loud, the step-dancing too audible, nor must the gambling be seen, or else you are in for it. But still in most cells these enjoyments occur every night.

The object of this paper is to try to impress the public with the necessity of prison reform.

The associate system is calculated to increase the criminal classes both in numbers and capacity for crime.

A boy of 17 years of age is sentenced to say, three years. After his first nine months he is put in the boys' yard. Boys are the same the world over, and, in jail, bad, vile and criminal boy abound. The lad has, perhaps, committed his first offence, and, very often, a venial one. He is surrounded in his yard by boys worse than himself, for the longer they stop the worse they become. At his work he is surrounded by older criminals — men who have been incarcerated for all sorts of crimes. Their conversation is not elevating, to say the least. And at night he is locked up in a small cell free from any observation for nearly 14 hours, with those who have committed all sorts of crimes and offences against society.

Bad men, under such circumstances, grow worse, better men grow bad, and a man who at the commencement of his criminal career had some remains of self-respect is speedily as depraved as the worst.

Amongst criminals themselves it is generally admitted that were the authorities to discharge a long-timer after the completion of his separate treatment, it would have a deterrent effect — they would never care to risk a second conviction. But after their long intercourse under the present system with their fellow prisoners they became hardened and reckless, and, instead of looking back upon their gaol life with horror, are apt, when undergoing any sort of privation, or even compelled to work hard, to wish they were once more in "chokie."

Warders say that when once a man is convicted, they look with certainty upon his re-appearance in the jail.

Sources:

- An Extraordinary Contrast Part I. (1888, January 5). The Australian Star (Sydney, NSW : 1887 - 1909), p. 3.

- An Extraordinary Contrast Part II. (1888, January 6). The Australian Star (Sydney, NSW : 1887 - 1909), p. 2.

No comments