The gang plundered in a most systematic and relentless way, and did not scruple to shoot down any who made an attempt at remonstrance or resistance. Attacking the settlers of New Norfolk, they took away their firearms, broke open their homesteads, burned their wheat stacks and houses, and carried off all the portable property upon which they could lay their hands. Even the Police Magistrate and the district constable at Pittwater had a fire-stick applied to their stacks, and counted themselves fortunate not to have lost house and life as well. A second attack on New Norfolk was unsuccessfully opposed by a mixed force of settlers and soldiers: the bushrangers shot two, captured a third, and drove their opponents from the settlement. But a second party of soldiers, sent post haste from Hobart Town on receipt of the news, surprised the gang in the midst of its marauding, and mortally wounded its leader. Two others were captured, but Howe and the rest got clean away in the darkness of the night. When Whitehead was wounded he immediately appealed to Howe to cut off his head, so that the pursuers should not get the reward; for it had been arranged between them that whichever survived should do his fallen comrade this service. Howe carried out the agreement, but the head was found in the bush later on, and the body was carried to Hobart and gibbeted at Hunter's Island.

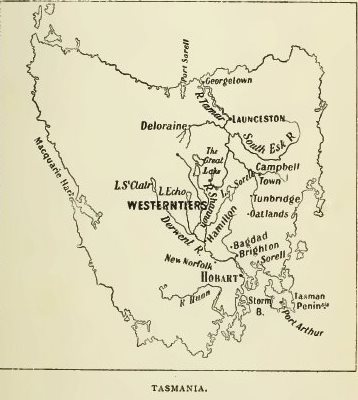

After the death of Whitehead, Howe assumed the leadership of the gang, and at once led them on to fresh depredations. Their movements were very rapid, and covered a large area of country; one day they were reported at Launceston and shortly afterwards at Bagdad, a hundred miles off, where their scouts had given them news of rich booty.

Howe assumed the airs of a chief, and introduced naval rule into his camp. The members were compelled to subscribe to articles of obedience, the oath was administered on a Prayer Book, and penalties were exacted for any breach of discipline. He styled himself "Governor of the Rangers", as opposed to the representative of Royalty in Hobart Town, whom he called "Governor of the Town".

In all his marauding expeditions he was attended by a faithful aboriginal girl named Black Mary, who must have been invaluable to him both as scout and as servant. But his gratitude was as feeble as his morals, and her fidelity had but ill reward. Some soldiers of the 46th, who had been despatched in pursuit of the gang, once came across Howe and Mary apart from the others. Howe ran for his life: the girl could not keep up with him; he saw that the soldiers must overtake her and capture him if he remained with her; so he turned and fired upon her. She fell and was seized. Her master, throwing away his knapsack and gun, plunged into the scrub, through which his pursuers could not follow him. In the knapsack was a primitive-looking book of kangaroo skin, upon which were recorded, in letters of blood, the dreams of greatness which filled the bushranger's mind.

Mary could not forgive her faithless lord. The wounds were not mortal, and when they had healed she determined to have her revenge. Leading his pursuers, she tracked the hunted bushranger from place to place, until the chase grew so close and hot that Howe offered to surrender on terms. He wrote to the "Governor of the Town" and managed to get the letter forwarded by a person who was able to go between the two "Governors" without injury to himself. And, strange to say, Governor Sorell entertained the proposals made by "Governor" Howe, and actually sent one of his officers to treat with him.

Outlaws have dictated terms on many occasions, but never, I venture to say, under such conditions. Society, as West says, must have been on the verge of dissolution when letters and messages could pass between the Government and an outlaw. The surrender took place in due course, and Howe was once more a prisoner.

His gang, however, was by no means dispersed. Howe had promised to betray them, but the information he gave was of very little use, and things were soon worse than ever. A reign of terror began. The richer settlers abandoned their homes and took refuge in the town. The boat that carried provisions between Launceston and Georgetown was seized, and recruits obtained from its crew. The Governor appealed to the public, who raised by subscription a reward for the gang's capture. A party of soldiers ran them to earth, but could do nothing against their well-posted force but kill its new leader.

During this time Howe was in prison. Notwithstanding his previous character, he was allowed considerable freedom of movement by the authorities, and soon took advantage of it. He pleaded ill-health, was allowed to walk abroad in charge of a constable, and walked very much abroad, leaving the constable in the rear. Soon he was again at the head of a party, which included some of his old companions in arms. But one night trouble arose; two of the gang incurred the anger of the leader, who decided to make short work of them. At midnight, while both were sleeping, he crept upon them, and put an end to one by cutting his throat from ear to ear, and to the other by clubbing him on the head with the stock of a gun.

By degrees the gang was reduced to three—Howe, Watts, and Brown—and more trouble came. Brown surrendered himself to the authorities, and Watts plotted against his leader to save his own life. At this time there were rewards out for Howe and Watts amounting to £100 each, and knowing this, the men were increasingly watchful; but Watts placed himself in communication with a stock-keeper on a station near, and elaborated plans for capturing Howe. The latter suspected that something was wrong, however, and accused Watts of infidelity, which the latter denied; as a proof that he was prepared to argue the matter calmly he suggested that each should knock out the priming of his gun before coming to an explanation. Howe agreed: Drewe, the stock-keeper (probably an old confederate), came up, and the three proceeded to "camp". As Howe stooped to fan the fire into a blaze with his hat, Watts suddenly pounced upon him, threw him down, and with Drewe's assistance secured his hands. They then took his knife and pistols and went on with breakfast, giving Howe to understand that they intended to take him straight into Hobart Town. When all was ready they started on their journey. Watts going first with a gun in his hand; Howe, with his hands bound, coming next; and Drewe bringing up the rear. They had not proceeded far, however, when the bound leader suddenly exerted his giant strength, snapped his bands, and sprang upon Watts, stabbing him in the back with a dirk which his captors had overlooked in their search. As Watts fell Howe seized his gun and fired at Drewe, shooting him dead. Strange to say, he did not stop to complete his work on Watts, but left him where he had fallen, doubtless thinking that the slow death would be a greater punishment. Watts managed to reach the town, however, and give information, afterwards being removed to Sydney, where he died of his wounds.

Once more free, Howe determined to act for himself, without trusting his liberty to companions; but he spent a terrible time. The Governor added a second hundred pounds to the first reward, as well as a free pardon and a passage to England to any prisoner who might succeed in bringing him to justice. Hunted more persistently than a wild dog would have been, Howe betook himself to the mountains, and only appeared when hunger or lack of ammunition forced him to the settlements: at such times his reputation and his savage looks gained him time to seize the supplies he wanted before his victims could make up their minds to resist him.

Bonwick, who was well acquainted with the locality, thus describes his hiding place:– "Badgered on all sides, he chose a retreat among the mountain fastnesses of the Upper Shannon, a dreary solitude of cloud-land, the rocky home of hermit eagles. On this elevated plateau—contiguous to the almost bottomless lakes from whose crater-formed recesses in ancient days torrents of liquid fire poured forth upon the plains of Tasmania, or rose uplifted in basaltic masses like frowning Wellington;—within sight of lofty hills of snow, having the Peak of Teneriffe to the south. Frenchman's Cap and Byron to the west. Miller's Bluff to the east, and the serrated crest of the Western Tier to the north; entrenched in dense woods, with surrounding forests of dead poles through whose leafless passages the wind harshly whistled in a storm;—thus situated amidst some of the sublimest scenes of nature, away from suffering and degraded humanity, the lonely bushranger was confronted with his God and his own conscience."

In October, 1818, a former accomplice in the pay of a man named Worrall, who had determined to capture him, lured him to his fate by promises of food. The story of his capture is given in the captor's own words in the Military Sketch Book, and I cannot do better than repeat it here:–

"I was now," says Worrall, "determined to make a push for the capture of this villain, Mick Howe, for which I was promised a passage to England in the next ship that sailed, and the amount of reward laid upon his head. I found out a man of the name of Warburton, who was in the habit of hunting kangaroos for their skins, and who had frequently met Howe during his excursions, and sometimes furnished him with ammunition. He gave me such an account of Howe's habits, that I felt convinced we could take him with a little assistance. I therefore spoke to a man named Pugh, belonging to the 48th Regiment, one who I knew was a most cool and resolute fellow. He immediately entered into my views, and having applied to Major Bell, his commanding officer, he was recommended by him to the Governor, by whom he was permitted to act, and allowed to join us; so he and I went directly to Warburton, who heartily entered into the scheme, and all things were arranged for putting it into execution. The plan was this:– Pugh and I were to remain in Warburton's hut, while Warburton himself was to fall into Howe's way. The hut was on the River Shannon, standing so completely by itself, and so out of the track of anybody who might be feared by Howe, that there was every probability of accomplishing our wishes, and "scotch the snake", as they say, if not kill it. Pugh and I accordingly proceeded to the appointed hut. We arrived there before daybreak, and having made a hearty breakfast, Warburton set out to seek Howe. He took no arms with him, in order to still more effectually carry his point, but Pugh and I were provided with muskets and pistols. The sun had just been an hour up when we saw Warburton and Howe upon the top of the hill coming towards the hut. We expected they would be with us in a quarter of an hour, and so we sat down upon the trunk of a tree inside the hut calmly waiting their arrival. An hour passed but they did not come, and I crept to the door cautiously and peeped out. There I saw them standing within a hundred yards of us in earnest conversation; as I learned afterwards the delay arose from Howe suspecting that all was not right; I drew back from the door to my station, and about ten minutes after this we plainly heard footsteps and the voice of Warburton. Another moment and Howe slowly entered the hut—his gun presented and cocked. The instant he espied us he cried out "Is that your game?" and immediately fired, but Pugh's activity prevented the shot from taking effect, for he knocked the gun aside. Howe ran off like a wolf. I fired but missed. Pugh then halted and took aim at him, but also missed. I immediately flung away the gun and ran after Howe; Pugh also pursued; Warburton was a considerable distance away. I ran very fast; so did Howe; and if he had not fallen down an unexpected bank, I should not have been fleet enough for him. This fall, however, brought me up with him; he was on his legs and preparing to climb a broken bank, which would have given him a free run into the wood, when I presented my pistol at him and desired him to stand; he drew forth another, but did not level it at me. We were then about fifteen yards from each other, the bank he fell from being between us. He stared at me with astonishment, and to tell you the truth, I was a little astonished at him, for he was covered with patches of kangaroo skins, and wore a black beard—a haversack and powder horn slung across his shoulders. I wore my beard also as I do now, and a curious pair we looked. After a moment's pause he cried out. "Black beard against grey beard for a million!" and fired; I slapped at him, and I believe hit him, for he staggered, but rallied again, and was clearing the bank between him and me when Pugh ran up and with the butt end of his firelock knocked him down, jumped after him, and battered his brains out, just as he was opening a clasp knife to defend himself."

So closed the last act in Howe's career. His head was cut off and exhibited in Hobart Town, and those who had feared him felt safe at last. Many murders were attributed to him besides those referred to. It was said that among his victims were two of his boon companions, who had committed some trifling offence, and concerning one of these it was said that Howe tied his hands and feet before shooting him.

The remaining members of the original gang all met a deservedly ignominious fate, most of them before Howe's death. M'Guire and Burne were tried and executed for the murder of Carlisle. Geary, who assumed command during the interregnum caused by Howe's temporary surrender, was shot dead in an encounter with the police. Lepton had his throat cut by a recent addition to the ranks named Hillier, who also nearly "did for" Collier at the same time. The latter was subsequently hanged in Hobart, after being tried in Sydney and convicted. Other men who joined the gang at different times also came to a violent end.

Source: The Bushrangers (1915, February 12). The Farmer and Settler (Sydney, NSW : 1906 - 1955), p. 6.

No comments