THE BUSHRANGERS

THE RISE OF BUSHRANGING IN CONVICT DAYS.

CHAPTER 1.

HISTORICAL SKETCH.

The early history of bushranging in Australia will never be written, for the facts have never been recorded. Moreover, the first men that "took to the bush" were neither important nor interesting enough to obtain more than a passing mention in those Governors' despatches that are our chief authorities for early colonial history. Owing to the stringency of the military rule during the first years of convict settlement, the lack of knowledge of the country, and the absence of prey in the shape of men with money or other possessions (the aborigines being the only occupants of the country outside the properly formed settlements), those that were then called bushrangers were simply men that had broken away from their gangs in the hope of escaping from the torture of labor under Government.

The name bushranger has been made to carry a very different meaning since then, having been applied to men who, some from choice and some from necessity, ranged the bush as freebooters, "sticking-up" settlers and travellers and demanding in the style of the period "your money or your life."

In the year 1796 Governor Hunter mentioned in despatches "a gang or two of banditti who have armed themselves, and infest the country all round, committing robberies upon defenceless people, and frequently joining the natives for that purpose." On August 24, 1806, the "Sydney Gazette" mentions one "Murphy the bushranger" as having been caught, and then, through carelessness, let go again. But scarcely anything is known of the hundreds of unfortunate men that slipped away into the inhospitable wilds that then surrounded the penal settlement on every hand, kept themselves alive for some time by raids upon the outlying farms or by companying with the blacks, and in the end died off in such numbers that an early explorer declared he had counted on one trip fifty skeletons.

In Van Diemen's Land — for many years a "Concentration Camp" for the worst class of convicts, who had added to their original offence a record of new crimes in Australia — the escaped convict was a more virulent evil, and his doings smacked of a brutal thirst for vengeance, not only on his former gaolers, but on all, white and black alike, who were less fiendish than himself. The early necessities of the settlement, which compelled the authorities to relax their rule and allow many of the convicts to hunt for sustenance, favored the growth of small bands of "looters," who made raids upon the settlers in the bush, and even upon the inhabitants of the principal townships. These banditti had so increased in numbers by 1814 that Colonel Davey, the second Lieutenant-Governor of Van Diemen's Land, declared the whole colony under martial law, in the hope of checking their ravages, and he punished by flogging all persons, free as well as bond, that left their houses by night.

A desire for freedom no doubt excited the convicts in the first instance to break from control and take to the bush, and the pangs of hunger led them to plunder; but they soon assumed a boldness of lawlessness that fairly intimidated the Government. Toward the close of 1813 the colony of Van Diemen's Land was reduced to the greatest distress by their raids; and Governor Macquarie, in despair, offered to pardon all that surrendered within six months, provided that they had not committed murder — an offer that was taken advantage of by many, who nevertheless resumed their evil occupation shortly afterwards.

Among the worst of these was Michael Howe, whose story — as a typical one — is told at greater length later in these pages. Lemon, another of them, who particularly affected the neighborhood of Oatlands, has been described for us (with a comrade) in words that may picture his class: "Two savage-looking fellows emerged one from each side of the path. They were dressed in kangaroo-skins, with sandals of the same on their feet, and knapsacks on their backs; each carried a musket, and one had a brace of pistols stuck in his girdle." The author from whom I quote — Mr. Parker, a barrister of those days — goes on a little later to describe the bushrangers' hut, in a dense forest only thirty-six miles from Hobart. "The hut was constructed of turf, low and uncomfortable in the extreme, covered with sheets of bark stripped from the forest trees. The fireplace, also of turf, lined with stones at the bottom, was at one end of the hut, and within it a huge fire soon burned."

Among the worst of these was Michael Howe, whose story — as a typical one — is told at greater length later in these pages. Lemon, another of them, who particularly affected the neighborhood of Oatlands, has been described for us (with a comrade) in words that may picture his class: "Two savage-looking fellows emerged one from each side of the path. They were dressed in kangaroo-skins, with sandals of the same on their feet, and knapsacks on their backs; each carried a musket, and one had a brace of pistols stuck in his girdle." The author from whom I quote — Mr. Parker, a barrister of those days — goes on a little later to describe the bushrangers' hut, in a dense forest only thirty-six miles from Hobart. "The hut was constructed of turf, low and uncomfortable in the extreme, covered with sheets of bark stripped from the forest trees. The fireplace, also of turf, lined with stones at the bottom, was at one end of the hut, and within it a huge fire soon burned."

Lemon and his mate were at last tracked to this hut. Lemon was shot, and the companion was forced to cut off his head, place it in a bag, and march with it to Hobart between his two captors. But punishment of this kind, brutal as it may seem, was courtesy compared with the deeds of the bushrangers themselves. Dunne, one of Brady's gang (whose depredations are narrated in another chapter) was loathed even by some of his mates. One case will serve to show the villain's cruelty. When out in the bush he sought to get hold of a rather good looking black gin, who was living with her husband. The blackfellow naturally objected, and with scant ceremony Dunne put a rifle bullet through his breast. The poor gin, heart-broken at the death of her husband, refused to leave the mutilated body; so with devilish brutality Dunne cut off the blackfellows head, drilled a hole through it, and suspended it by a string round the neck of the outraged wife. Drawing his knife he drove her onward at its point to his bush retreat — the den, indeed, of a tiger.

A similar story is told of Jeffries, known as "The Monster," with the difference, that his victim was a white woman, whose baby was but newly born. In rage, because his captive did not walk fast enough, he dashed the child's brains out against a tree.

Yet even men of this stamp found sympathisers. When Dunne was hanged his admirers presented him with an elegant cedar coffin, and a hundred of them followed it to the grave. For the bushranger, as says James Bonwick, "was, in general, looked upon as a sort of martyr to convictism. He had experienced the shame, the lash, the brutal taunt, from which they too had suffered. It was he that had risen against the tyranny of their prison despot, and the dread consequences of their criminal law. He was the bold Robin Hood of their morning songs, and he was now the unfortunate victim of legal oppression, the captured of the chase. Without denying the atrocities of his career, they would discover many extenuations for his crimes. His reckless daring would be the noblest chivalry; and the jovial freedom of his manners, the frankest generosity. His immoral jests would be cherished for posterity, and the eclat of his life and death would stimulate the ambition of sympathising souls. The very gallows had a charm."

There was, of course, another side to the question. Convict life was hard at best, and was often made almost unbearable by the petty cruelties of the prison official or the station overseer. It is worth while, by way of representing this other side, to reprint here a narrative that appeared in one of the leading London journals of 1845, and which was then vouched for by the writer as correct in every detail.

In crossing the country one day, and at a distance from any habitation, Mr. Thornley, a settler, to his surprise and fear, beheld at a short distance approaching him a noted bushranger, known by the name of "The Gipsy," who had latterly, with a band of associates, become the dread of the colony. He was a tall, well-made man, one apparently above the ordinary character of convicts, and whom it was distressing to see in such a situation. The parties approached each other with mutual distrust. Thornley knew he had a desperate character to deal with, and pointed his gun at him, but the bushranger seemed desirous of a parley, and after a few words, says the writer, he laid his gun quietly on the grass, and then passed round me, and sat down at a few yards distance, so that I was between him and his weapon. "Well, Mr. Thornley," said he, "will that do? You see I am now unarmed. I don't ask you to do the same, because I cannot expect you to trust to me, but the truth is, I want to have a little talk with you. I have something on my mind that weighs heavy on me, and whom to speak to I do not know. I know your character, and that you have never been hard on your Government men, as some are. At any rate, speak to someone I must. Are you inclined to listen to me ?"

I was exceedingly moved at this unexpected appeal to me at such a time and in such a place. There was no sound, and no object save ourselves, to disturb the vast solitude of the wilderness. Below us flowed the Clyde, beneath an abrupt precipice; around were undulating hills, almost bare of trees; in the distance towered the snowy mountain which formed the boundary to the landscape. I looked at my companion doubtfully, for I had heard so many stories of the treachery of the bushrangers that I feared for a moment that this acting might only be a trick to throw me off my guard. Besides, this was the very man whom I knew to have been at the head of the party of bushrangers that had been captured at the Great Lake.

He observed the doubt and hesitation which were expressed in my looks, and pointed to his gun, which was on the other side of me.

"What more can I do," said he, "to convince you that I meditate neither violence nor treachery against you? Indeed, when you know my purpose, you will see that they would defeat my own object."

"What is your purpose, then? Tell me at once — are you one of the late party of bushrangers who have done such mischief in the island ?"

"I am; and more than that, I am — or rather was — their leader. I planned the escape from Macquarie Harbor, and it was I who kept them together, and made them understand strength, and how to use it. But that's nothing now. I do not want to talk to you about that. But I tell you who and what I am, that you may see I have no disguise with you, because I have a great favor — a very great favor — to ask of you, and if I can obtain it from you on no other terms, I am almost inclined to say, take me to camp as your prisoner, and let the capture of the Gipsy — ah ! I see you know that name, and the terror it has given to the merciless wretches who pursue me — I say, let the capture of the Gipsy, and his death if you will (for it must come to that at last), be the price of the favor that I have to beg of you!"

"Speak on, my man," I said; "you have done some ill deeds, but this is not the time to taunt you with them. What do you want of me? If it is anything that an honest man can do, I promise you beforehand that I will do it."

"You will! Now listen to me. Perhaps you do not know that I have been in the colony ten years. I was a lifer. It's bad that; better hang a man at once than punish him for life. There ought to be a prospect and an end to suffering; then a man can look forward to something; he would have hope left. But never mind that. I only speak of it because I believe it was the feeling of despair that first led me wrong, and drove me from bad to worse. Shortly after my landing I was assigned to a very good master. There were not many settlers then, and we did not know so much of the country as we do now. As I was handy in many things, and able to earn money, I soon got my liberty on the old condition; that is by paying so much a week to my master. That trick is not played now, but it was then, and by some of the big ones too. However, all I cared for was my liberty, and was glad enough to get that for seven shillings a week. But still I was a Government prisoner, and that galled me; for I knew I was liable to lose my license at the caprice of my master, and to be called into Government employ. Besides, I got acquainted with a young woman, and married her, and then I felt the bitterness of slavery worse than ever; for I was attached to her sincerely, and I could not contemplate the chance of parting from her without pain. So about three years after I had been in this way, I made an attempt to escape with her in a vessel that was sailing for England. It was a mad scheme, I know, but what will not a man risk for his liberty ?"

"What led you to think of going back to England? What were you sent out here for?"

"I have no reason to care for hiding the truth. I was one of a gang of poachers in Herefordshire, and on a certain night we were surprised by the keepers, and somehow, I don't know how, we came to blows, and the long and the short of it is, one of the keepers was killed; and there's the truth of it."

"And you were tried for the murder "

"I and two others were; and one was hanged, and I and my mate were transported for life."

"Well, the less that's said about that the better; now go on with your story, but let me know what it is you would have me do for you."

"Well, the less that's said about that the better; now go on with your story, but let me know what it is you would have me do for you."

"I'll come to that presently, but I must tell you something about my story, or you will not understand me. I was discovered in the vessel, concealed among the casks, by the searching party, and brought on shore with my wife; and you know, I suppose, that the punishment is death. But Colonel Davey—he was Governor then—let me off, but I was condemned to work in chains in Government employ. This was a horrid life, and I determined not to stand it. There were one or two others in the chain gang all ready for a start into the bush, if they had any one to plan for them. I was always a good one at head work, and it was not long before I contrived one night to get rid of our fetters. There were three others besides myself. We got on top of the wall very cleverly, and first one dropped down (it was as dark as pitch, and we could not see what became of him), then another dropped, and then the third. Not a word was spoken. I was the last, and glad enough was I when I felt myself sliding down the rope outside the yard. But I had to grin on the other side of my mouth when I came to the bottom. One of the sneaks whom I had trusted had betrayed us, and I found myself in the arms of two constables, who grasped me tightly. I gave one of them a sickener, and could have easily managed the other, but he gave the alarm, and then lots of others sprang up, and lights and soldiers appeared. I was overpowered by so many. They bound my arms, and then I was tried for the attempt to escape and the assault on the constable, and condemned to Macquarie Harbour for life.

|

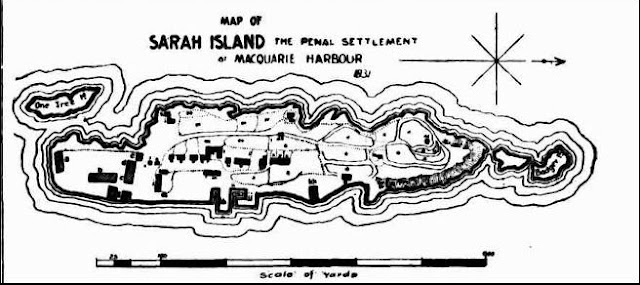

| Map of Sarah Island - The Penal Settlement of Macquarie Harbour 1831 |

"I have not told you that my wife brought me a child. It is now seven years old. I loved that child, Mr. Thornley, more than a person usually loves his child. It was all in all to me. It was the only bright thing I had to look upon. When I was sentenced to Macquarie Harbor for life, it would have been a mercy to put me to death. I should have put myself to death, if it had not been for the thought of that little girl. Well, sir, I will not say more about that. When a man takes to the bush, and has done what I have done, he is thought to be a monster without feeling or affection. But people don't understand us. There is no man, sir, depend upon it, so bad that he has not some good in him, and I have some experience; for I have seen the worst of us — the very worst — in the most horrible of all conditions — for that Macquarie Harbor is a real hell upon earth! There is no time to tell you about the hardships which the prisoners suffer in that horrible place — it soon kills them. But my greatest misery was being deprived of my little girl — my plaything my darling — my life! I had not been at Macquarie Harbor a month before news came that my wife was dead. I'll tell you the truth, sir; attached to her as I was, I was rather glad than sorry for it. I could not bear the thought of her falling into anybody else's hands, and as our separation was now absolutely and hopelessly for ever — it is the truth — I was rather glad than sorry when I heard of her death. But my poor little child! I thought of her night and day, wondering and thinking what would become of her! I could think of nothing else! At last my thoughts began to turn to the possibility of escaping from Macquarie Harbor, desperate as the attempt appeared; for, to cross the bush without arms, and without provisions, exposed to the attacks of the natives, seemed all but an impossibility. But almost anything may be done by resolution and patience, and watching your opportunity."

[The escape having been effected, fifteen prisoners in all having taken to the bush.] "We scrambled away as well as we could, till we got a little distance off, and out of hearing, and then we set to with a will, and rid ourselves of our fetters, all except three, and these were too tightly fitted to be got off on a sudden without better tools. We got the three chained men along with us, however, as well as we could for we would not leave them, so we helped them on by turns, and the next day, when we were more easy, we contrived to rid them of their encumbrances. We hastened on all night. I ought to tell you that we heard the bell rung and the alarm given, but we had gained an hour good, and the ungagging of the sentinels and the overseers, and hearing their story, took up some time no doubt. Besides, it is not easy to hit on a track in the dusk, and as there were fourteen of us, armed with two muskets, our pursuers would not proceed as briskly as they otherwise might, and would not scatter themselves to look after us. We were without provisions, but we did not care about that, and not being used to long walks, we were soon knocked up. But the desire of liberty kept us up, and we struck right across the country in as straight a line as we could guess. The second day we were all very sick and faint, and the night before was very cold, and we were cramped and unfit to travel. The second night we all crept into a cave, which was sandy inside, where we lay pretty warm, but we were ravenously hungry. We might have shot more than one kangaroo that day, but it was agreed that we should not fire, lest the report of our gun should betray our resting place to our pursuers. As we lay huddled together, we heard the opossums squealing in the tress about, and two of us, who were least tired, tried to get some of them. When we climbed up the trees, they sprang away like squirrels, and we had no chance with them that way; besides, it was dark, and we could distinguish them only faintly and obscurely. We did contrive, however, to kill five by pelting them on a long overhanging bough, but they remained suspended by their tails, and did not drop, although dead. To hungry men a dead opossum is something! so one of us contrived to climb to them and get them down; and then we lighted a fire in the cave, quite at the extremity inside, to prevent the flame from being seen, and roasted them as the natives do. They were horrid rank things to eat, and almost made us sick, hungry as we were; but I don't think a hair of them was left among us. The next day we shot a kangaroo, but we feared to light a fire because of the smoke, so we ate it raw.

"We first stuck on the outskirts of New Norfolk, and we debated what we should do. Some were for attacking the settlement, and getting arms, but I persuaded them that it would be better for us to endeavor to seize some small vessel, and escape altogether from the colony, and in the meantime to keep ourselves close, and not to give any alarm. My companions agreed to this, and we struck across the country to Brighton Plains, and so to Pitt Water, where we expected to find some large boats, or perhaps some small vessel, by means of which we might get away."

"And how is it that you did not follow that plan ?"

"We did follow it. We got to Pitt Water, and lay snug there for a while, but we were obliged to rob a settler's house of provisions for food, and that first gave the alarm. We made a dash at a boat, but it was too late; precautions had been taken, and the soldiers were out after us. We were then obliged to retreat from Pitt Water, intending to get into the neighborhood of the lakes, and go further westward if necessary, and retreat to the coast, where we judged we should be too far off to be molested."

"You did a great deal of mischief before you left it, if all the stories are true?"

"We did, Mr. Thornley, I own it, but my men were determined to have arms, and the settlers of course resisted, and some of my men got wounded, and that made them savage."

"And afterwards you attacked poor Moss's cottage?"

"My men had been told that he had a large sum in dollars at his hut — I am surprised that settlers can be so foolish as to take valuables into the bush — that was all they wanted."

"But why did you take poor Moss along with you?"

"I was obliged to do it to save his life. Some of my men would have knocked him on the head, if I had not prevented them. It is true, Mr. Thornley, it is indeed — I saved his life."

"Well, that's something in your favor. And now, as the sun is sinking fast, and as the dusk will come on us presently, tell me at once what you would have me do for you."

"Mr. Thornley," said the bushranger, "I have told you of my little girl. I have seen her since the dispersion of my party at the Great Lake. You know that I and another escaped. Since then I have ventured in disguise into Hobart Town itself. The sight of her, and her embraces, have produced in me a strange feeling. I would willingly sacrifice my life to do her good, and I cannot conceal from myself that the chances are that I must be taken at last, and that if I do not perish miserably in the bush I shall be betrayed, and shot or hanged."

"'And what can I do to prevent it?"

"You can do nothing to prevent that end, for I know that I am too deep in for it to be pardoned. If I were to give myself up the Government would be obliged to hang me for example's sake. No, no; I know my own condition, and I foresee my own fate. It is not of myself that I am thinking, but of my child. Mr. Thornley, will you do this for me — will you do an act of kindness and charity to a wretched man, who has only one thing to care for in this world? I know it is much to ask, and that I ought not to be disappointed if you refuse it. Will you keep an eye on my poor child, and so far as you can, protect her? I cannot ask you to provide for her, but be her protector, and let her little innocent heart know that there is some one in the wide world to whom she may look up for advice — for assistance, perhaps, in difficulty; at all events, for kindness and sympathy; this is my request. Will you have so much compassion on the poor, blasted and hunted bushranger, as to promise to do for me this act of kindness?"

I gazed with astonishment, and I must add, not without visible concern, on the passionate appeal of this desperate man in behalf of his child. I saw he was in earnest — there is no mistaking a man under such circumstances. I rapidly contemplated all the inconvenience of such an awkward charge as a hanged bushranger's orphan. As these thoughts passed through my mind, I caught the eye of the father. There was an expression in it of such utter abandonment of everything but the fate of his little daughter, which seemed to depend on my answer, that I was fairly overcome, and could not refuse him. "I will look after her," I said, "but there must be no more blood on your hands; you must promise me that. She shall be cared for, and now that I have said it, that's enough — I never break my word."

"Enough," said he, "and more than I expected. I thank you for this, Mr. Thornley. I could thank you on my knees. But what is that? Look there! A man on horseback, and more on foot. I must be on my guard."

As he spoke, the horseman galloped swiftly towards us. The men on foot came on in a body, and I perceived that they were a party of soldiers. The Gipsy regarded them earnestly for a moment, and then ran to his gun, but in his eagerness he tripped and fell. The horseman, who was one of the constables from Hobart Town, was too quick for him. Before he could recover himself, and seize his gun, the horseman was upon him. "Surrender, you villain, or I'll shoot you."

The Gipsy clutched the horse's bridle, which reared and plunged, throwing the constable from his seat. He was a powerful and active man, and catching hold of the Gipsy in his descent, he grappled with him and tried to pinion his arms. He failed in this, and a fearful struggle took place between them. "Come on." cried the constable to the soldiers, "let us take him alive."

The soldiers came on at a run. In the meantime, the constable had got the Gipsy down, and the soldiers were close at hand, when suddenly, and with a convulsive effort, the Gipsy got his arms round the body of his captor, and with desperate efforts, rolled himself round and round, with the constable interlaced in his arms, to the edge of the precipice. "For God's sake," cried the constable, with a shriek of agony, "help, help ! We shall be over!" But it was too late. The soldiers were in the act of grasping the wretched man's clothes when the bushranger, with a last convulsive struggle, whirled the body of his antagonist over the precipice, himself accompanying him in his fall. We gazed over the ridge, and beheld the bodies of the two clasped fast together, turning over and over in the air, till they came with a terrible shock to the ground, smashed and lifeless. As the precipice overhung the river, the bodies had not far to roll before they splashed into the water, and we saw them no more.

The reader may be interested to know that Mr. Thornley was better than his word. He sought the daughter of the unfortunate man, took her home to his house, and afterwards sent her to England.

Sources: The Bushrangers (1915, February 5). The Farmer and Settler (Sydney, NSW : 1906 - 1955), p. 3.

No comments