The gangs of bushrangers that infested New South Wales in the early days were not so numerous as those in Van Diemen's Land, neither were they as a rule so cruel and bloodthirsty. But some of the outlaws were terrible characters, and during the period they carried on their nefarious operations the country over which they roamed was kept in a continual state of unrest and fear.

Up to 1815 bushranging—and that of the more harmless kind—was confined to the country between Sydney and Emu Plains, for the first difficulty of mountain travelling had not then been overcome. The men who "took the bush" had escaped either from the barracks at Sydney, or from the road and ironed gangs about Windsor, Richmond, Parramatta, and Emu Plains, or had absconded from the service of townsmen or settlers in the localities named, and were well content if they could, even for a short time only, eke out a bare existence among the roving tribes of half-civilized blacks, or by occasional visits to the few cultivated fields or barns not guarded by the military. These men were, however, sooner or later driven by starvation to surrender, glad to seek food although associated with stripes from the "cat" or drudgery in chains, heavier than that from which they had sought relief by flight. Some were shot down by the soldiers in the bush; not a few fell victims to the blackfellow's spear or waddy; others lost themselves in the bush and perished, their bleached bones—or that portion of them which had been left by the native dogs—being afterwards found near some "blind" gully or amidst the scrub.

The opening of the mountain road from Emu Plains to Bathurst not only extended the area of rapine to the new settlements on the western plains, but gave criminals a far better chance of intercepting valuable booty while in transit over the rugged tableland of the Blue Mountains. But while, as we shall see, the Bathurst district had its full share of trouble, it was still nearer Sydney that plunder was sought by the more daring spirits.

The following extract from a Sydney newspaper of 1826 at once illustrates this type of crime, and brings vividly before our eyes the closeness of the bush to Sydney in those early days:–

Two daring bushrangers, named Mustin and Watkins, were captured on Monday last, between four and five o'clock in the morning, near Burwood, six or seven miles distant from Sydney, by Major Lockyer, J.P., and a party of military, together with Constables Sutland and O'Meara (and some others) of the police. The Superintendent of Police, together with a full bench of magistrates, was engaged for a considerable length of time on Monday in receiving depositions connected with some of the atrocities perpetrated by these desperadoes, of which, it is thought, a considerable number remain undeveloped. It appeared that, on Friday last, between eight and nine o'clock at night, three men, armed with guns and pistols, two of whom were the prisoners, entered the house of Mr. James Coles, publican, on the Liverpool-road, after all the family, with the exception of a man servant and a girl, had retired to rest. Immediately on their entrance, having ascertained that the master of the house was in bed, they, with many threats in case of disobedience, directed the servants to remain in the bar, leaving one of their party as a guard over them, whilst the other two proceeded to the bedroom of Mr. Coles; and telling him that they would blow his brains out if he made the least resistance proceeded to search the place, and demanded what money he had in his possession. Mr. Coles denied having any in the house; but the robbers having discovered a box which they suspected to contain what they were in search of, one of them presented his musket, stating that he would immediately blow it open if the keys were not instantly delivered to him. One of the family, apprehensive of personal violence being resorted to, accordingly complied with the demand by giving up the keys, when the robbers possessed themselves of all the money they could find, amounting to upwards of £60, together with a watch and seals and a pistol. They afterwards repaired to a storeroom and took away a leg of pork and a pig's head; and returning to the bar they ordered the female servant to fill them half a gallon of brandy and the same quantity of wine, which having obtained, together with about four pounds weight of sugar and a pair of boots which hung in the bar, they departed.

It appeared, also, that the same party paid a visit to Burwood, the residence of Dr. Dulhunty, on the following night, Saturday. The noise of dogs barking alarmed the family, and Mr. Dulhunty, jun., immediately proceeded to the hut of the Government servants, at some distance from the house, which he found, on his entrance, to be filled with strange men. Some excuse was set up that they belonged to a neighbouring road party, and Mr. Dulhunty returned to the house, when after some time receiving a second alarm from one of his family, having seen a flash from a gun or pistol in the direction of the hut, he again went out, armed with a pistol and stick, and finding the same party, he ordered them away, when using some imprecations they rushed out, and one of them snapped a pistol at Mr. Dulhunty, which fortunately missed fire. A scuffle ensued, in which Mr. Dulhunty was knocked down, and beaten by one of the ruffians with the butt end of a pistol. He afterwards ran towards the house to procure assistance, and on his way perceived a man getting over a fence, at whom he presented a pistol, and happening to slip at the moment, the pistol went off as he fell, and the fellow escaped, but it is thought received his death wound on that occasion, and was hidden in the bush by his companions, as he has not since been discovered. The robbers succeeded in effecting their escape on Saturday night, and on Sunday morning, previous to coming to town to give information to the police, Mr. Dulhunty discovered part of a steel watch-chain, with a gold seal and keys appended, lying close to the fence, and near as he stated to a pool of blood. The chain and seals, together with a watch subsequently found with the prisoners, were identified by Mr. Coles as those taken from the premises on the preceding night. On Monday morning, the constables, accompanied by Major Lockyer, as a magistrate, and a party of soldiers, apprehended the prisoners in the bush, about a mile and a half from Burwood. They were concealed under two fallen trees, with a tarpaulin and brushwood over them, and, on being searched, the money taken from Mr. Coles was found in their possession when they were secured. Major Lockyer said to Mustin, "You are the man Mr. Dulhunty beat last night," he replied, "I am", and, after finding the money, when Major Lockyer directed a further search to be made about the place, Mustin said, "Oh! there is no occasion, you have got enough to hang fifty men." The boots taken from the house of Mr. Coles were identified at the police station, on the prisoner Watkins, and upon the Superintendent ordering them to be taken off, some of the bystanders overheard Mustin say, "You'll make a liar of your mother now, she always said you'd be hanged in your shoes, but you won't." They were yesterday fully committed.

In addition to the foregoing, we hasten to give the following from our Parramatta correspondent:–

About 11 o'clock on Saturday night last information reached Mr. John Thorn, Chief Constable of Parramatta, that a party of bushrangers were reconnoitering contiguous to the Western Toll-gate, in the Government Domain. Mr. Thorn, in consequence, accompanied by Wardsman Wells and Constable Ratty, aided also by Mr. Piesley, jun., proceeded to the toll-house, where the Chief Constable concerted that Constable Ratty should proceed with a large bundle down the road and counterfeit drunkenness, while the party made a circuitous route on the other side of the road in the bush. Constable Ratty proceeded as directed, and, when at the distance only of about 100 yards from the toll-house, four or five men, as stated by Ratty, jumped over and demanded the bundle: some of the party were armed. Ratty, as pre-directed, said, in a tone of voice to be heard by the party, "Well, if you must take the bundle, you must;" and one of the robbers then took it from him. Ratty immediately fired at and shot the man through the neck, on which two other shots were returned. The party then made up, when the foremost, Mr. John Piesley, found four men contending with Ratty. He fired at one, who fell, exclaiming "I am killed." The night was extremely dark, and the repeated flashes from the firearms rendered it still more impenetrable. Wells then fired, and Mr. Thorn and J. Piesley pursued another of the gang; Piesley fired, but missed him. They continued the pursuit, when the man took the fence. Mr. Thorn jumped also upon the fence, and as the robber was making into the bush, he fired, and the man fell, but before Mr. T. came up he rose, and ran a few yards and fell again, when he was secured. He was slightly wounded in the head by a ball. On coming up to the others of the party, it was discovered that Constable Ratty received a ball which penetrated the middle of his back, and passed through and lodged in his breast, within half and inch of the chin, where the ball was extracted; one of the three robbers that were shot escaped during the engagement, and it is with considerable regret I inform you, that another of them, when within about ten yards of the gaol, escaped from a constable into whose custody he had been given by the chief constable, while he re reported the circumstances to Dr. Harris. Two of the men's names so shot are Cook and Ward; the other, who escaped in the contest, is supposed to be Currey, runaways from the mountain iron gang. Patrols of the constables and military have since been sent out to scour the haunts of those marauders. Constable Ratty continues very ill indeed; considerable danger is apprehended; it is also doubtful whether the shot by which he was wounded was not fired by Wardsman Wells in mistake. Great credit is due to the chief constable and party (in which Mr. Piesley, jun., behaved in a very intrepid manner), for their exertions on this occasion.

When information of the foregoing depredations reached Colonel Dumaresq, the Private Secretary, he directly issued orders for three different detachments of military to proceed and surround the country in the neighbourhood of Liverpool Parramatta, &c., so as to completely cut off all chance for the bushrangers to escape; and it is mainly to this promptitude that the inhabitants of those districts are indebted for the capture of such desperadoes. It is worthy of remark, that so efficient have been the means adopted by the authorities of late, that scarcely a robbery has been committed, the perpetrators of which have not been secured within a few days after.

Here is a proclamation issued by Governor Darling a few years later. The Governor's attitude as lecturer on morals is not less interesting than the rewards which he deals out to the supporters of law and order:–

Colonial Secretary's Office:– The Governor having had under consideration the circumstances attending the death of MacNamara and the execution of Dalton, would fain encourage a hope that these awful events will awaken their abettors and associates in crime to a sense of their own situation, and will prove a useful lesson to others, less depraved and vicious, by deterring them from pursuing the like criminal and unlawful courses.

Let these but for a moment consider the short and dreadful career of these wretched men, and they will require no further warning. They would find that the utmost success would be no recompense for the anxiety of mind which they must have constantly experienced. Driven by their lawless pursuits to the foulest means—robbery and murder—of obtaining a precarious and guilty subsistence, they wandered in fear and dread of being overtaken, as they were at last; when, as if by the dispensation of a just and unerring Providence, MacNamara, the most atrocious offender of the two, was, in an instant, deprived of life, to be made answerable elsewhere for the crimes he has committed here; while Dalton was reserved to expiate his offences, which he did, in a few days, by an ignominious death on the gallows.

The fate of those who commit crimes, such as these men have been guilty of, is certain. They may escape for a moment: it will be for a moment only. The violated laws of God and man seek retribution, and will not suffer him to live who has taken away the life of another.

The Governor has been induced to offer these observations, that the inconsiderate (if there be men who commit crimes from want of consideration) may reflect and be made aware of the fate which inevitably awaits the commission of the more serious offences. On the hardened and more confirmed criminals he has but little hope of making any impression; but he trusts the effort to restrain those less devoted to vicious pursuits will not be entirely fruitless.

Robberies would be less frequent if receivers were not so numerous. These people may be assured that the utmost rigour of the law will be exercised in their case. Let the fate of Adlan and wife be a warning to them. The former is now under sentence of transportation to Norfolk Island for 14 years, and the latter to Moreton Bay for the same period. These people were the depositories of the plunder of Bowen and Jackson's houses: plunder acquired by acts of atrocity and outrage. The facility of disposing of stolen property leads to the commission of robberies and other serious crimes. Every bushman should feel that it is his duty to bring to conviction the receiver as he would an assassin, with whom the former is generally identified, and not unfrequently the abettor and instigator of his crimes.

It now becomes the more pleasing duty of the Governor, which he discharges with the sincerest satisfaction, to notice the meritorious conduct of Mr. John Thorn, the chief constable of Parramatta, who evinced the utmost intrepidity in pursuing and capturing Dalton.

Samuel Horn, wardsman of Parramatta, had not only the good fortune to escape the shot of MacNamara, which passed through his hat, but to kill him at the instant, his ball having lodged in MacNamara's breast.

Anthony Finn, ordinary constable, though not immediately concerned in the capture of either of the prisoners, has a fair claim to praise for his zeal on the occasion.

The Governor has been pleased to order, in consideration of the services of Mr. Thorn, that he shall receive a grant of land of one square mile, free of quit rent for ever; and that the deed shall specify the services for which the grant has been made.

Also, that Samuel Horn, holding a conditional pardon, shall receive a full pardon, with a grant of half a square mile of land, free of quit rent; and that Anthony Finn shall receive half a square mile of land, free of quit rent.

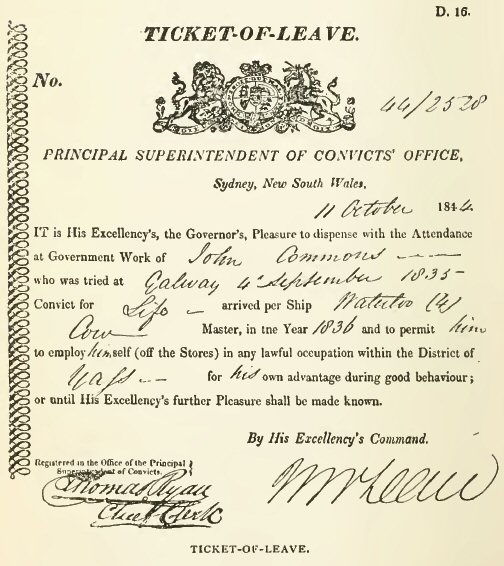

Having thus noticed the proceedings of the police of Parramatta, the Governor has equal satisfaction in expressing his approbation of the conduct of Mr. Frederick Meredith, junior, chief constable of Liverpool, in the attempt made on Jackson's house, in the month of March last. The assailants, five in number, men of desperate character (MacNamara and Dalton being of the party) were not beat off until after a sharp contest, in which Mr. Meredith was severely wounded. It is very satisfactory to the Governor to advert to the highly commendable conduct of Mr. Jackson, in defending his house: and he has been pleased to order that William Johnson, his assigned servant, who so courageously assisted in protecting his master's properly, shall receive a ticket-of-leave for his services on the occasion.

The Governor has further been pleased to order, as an acknowledgment of Mr. Meredith's services generally, and more especially on the occasion of the attack on Jackson, that he shall receive a grant of one square mile of land, the same as Mr. Thorn, the chief constable of Parramatta.

His Excellency cannot dismiss this subject without expressing the satisfaction he has derived from learning that Mr. Thorn and Mr. Meredith are both natives of the colony. They have availed themselves in the most spirited manner of the opportunity which their situation afforded them, of serving their country. Let their brethren generally imitate their example as the Government will foster them as its children.

A fuller account of Donohoe and Webber, the most notorious of the Cumberland bushrangers, and of the disturbed conditions which prevailed in the west during the twenties, and culminated in the Bathurst outbreak of 1830, will be found in the body of this work. After that date bushranging ceased to be the serious and all prevailing evil which it had become in the later twenties; though the exploits of Martin Cash in Van Diemen's Land, of the "Jew Boy" in the Hunter Valley, and of "Scotchey" and Witton in the Lachlan district, are important enough to receive separate treatment.

Mail coach robberies were not frequent in these earlier days, for the simple reason that there were then very few mail coaches to be "stuck up". Yet here is one case that occurred some years before the first sod of the first railway was turned at Redfern. A four-horse coach was proceeding with the "Royal mail" from Windsor to Sydney, there being several passengers, one of whom was on the box-seat with the driver, being well armed. At the foot of a hill the body of a man, lying upon his face, was seen in the middle of the road. The driver and his companion at once jumped to the conclusion that the man had fallen a victim to the bushrangers, and as they neared him, the coachman pulled up his team, handed the reins to his companion, and was in the act of descending to see if the man were really dead, when the whole party were startled by hearing the command, "Bail up, or you're dead men!" proceeding from the roadside, while the driver found himself looking fair into the barrel of a gun which was being pointed at him from the spot. At the same time the couchant bandit—for such he proved to be—sprang from the ground, turned the leading horses across the pole of the coach, and then covered the box-seat passenger with his blunderbus before he could get rid of the reins which the coachman had placed in his hands. The driver was then commanded to unhitch the horses, and the passengers were compelled to stand in a row on the roadside while one of the bushrangers "went through" their pockets and appropriated all their money and watches. The mailbags were then ripped open and the letters containing money extracted. The armed passenger had on a pair of trousers which took the fancy of the tallest of the robbers, and much to his chagrin he was compelled to disrobe, being left to shiver in the cold while the footpad drew the trousers over his own. Then taking the two leaders as "mounts", the bushrangers bid their victims "good-day" and departed, leaving the impoverished and frightened passengers to pursue the rest of the journey with two horses instead of four.

The gold discoveries gave bushranging a new lease of life. When the first gold fever set in, the crowds that left Sydney and other centres of population for the distant fields at Summerhill and the Turon, and later still, Adelong and the Ovens, contained not a small sprinkling of those who, if they were not then bushrangers, afterwards became such. It suited them better to waylay and rob those who were going to or retiring from the goldfields than to themselves handle pick and shovel and cradle, and they scrupled not to murder as well as rob if the hapless victims made even a show of resistance. As might be expected, it was the old convict element that first came to the front in this way, and I give in a subsequent chapter two typical sketches of their mode of procedure—the story of Day, the blacksmith bushranger, and that of Williams and Flanagan, the highway robbers of the St. Kilda-road.

But a new era was opening—that of the gangs, made up for the most part of freeborn men, the sons of small farmers settled on the Western mountain slopes, whose begetter and prime exemplar was Frank Gardiner. With them we approach times within the knowledge of most middle aged Australians; many of my readers will have very vivid recollections of the tumultuous years that followed 1860, when Gardiner and Ben Hall, in the west, and the Clarkes in the south, filled the newspapers with their audacity, and men's hearts with the fear of them. In this volume I have space to deal only with Gardiner and his mates: the full development of the gang-system, its wane towards the end of the sixties, and its unexpected revival in 1878 by the notorious Kellys, will require a volume of their own.

Source: The Bushrangers (1915, February 9). The Farmer and Settler (Sydney, NSW : 1906 - 1955), p. 6.

Source: The Bushrangers (1915, February 9). The Farmer and Settler (Sydney, NSW : 1906 - 1955), p. 6.

No comments