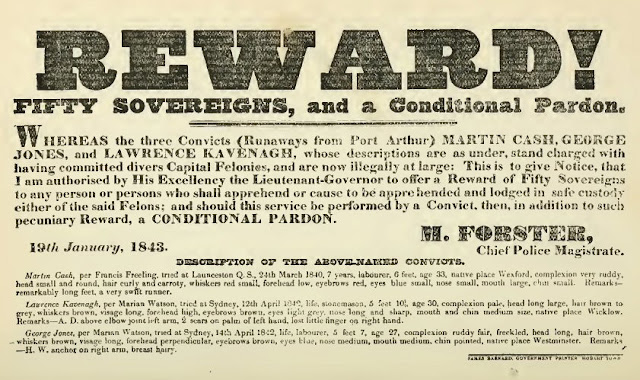

Among the more notorious of the Van Diemen's Land convict bushrangers of later days was Martin Cash, who, first singly, and then in association with Kavanagh and Jones, committed many depredations among the small settlers during 1843, and some time previous.

Cash was born in County Wexford, Ireland, and in 1827, at the age of about 18 years, was transported to Botany Bay for seven years for a deliberate attempt to murder a rival of whom he was jealous. He was well connected, and strenuous efforts were made by his wealthy friends and relatives to obtain a mitigation of the sentence, but without avail. He reached Sydney in February, 1828 (by the "Marquis of Huntley"), and was soon assigned to Mr. Bowman, of Richmond, who presently placed him on a cattle station in the Hunter district between Denman and Merriwa. By steady service in a responsible position he won favour from his master, and in due time obtained a ticket-of-leave, which enabled him to engage with another stock-owner as overseer at £20 per year. Gaining his freedom by similar good conduct, he determined to settle down on his own account; but here, after nine years of quiet, his troubles began. One morning he was innocently branding cattle for an acquaintance when two strangers rode up, watched the operation, and again rode away; after which his friend informed him the cattle were stolen beasts and the men who had ridden away would certainly report what they had seen. This alarmed Cash considerably. "Norfolk Island for life" was the punishment for illegally branding, and he made up his mind to leave the colony as quickly as possible. He took with him a woman whom he had some time before induced to leave her husband (for convenience we will call her Mrs. Cash in future), and, leaving her at Mudgee, set off to collect for sale some cattle of his own from a distant Namoi station. His treacherous friend of the branding episode had, however, sold these behind his back. Cash accordingly recouped himself from his friend's herd, sold the animals on his way back to Mudgee, picked up Mrs. Cash there, and struck southwards to Bathurst. His account of his stay there is an interesting contribution to the social history of the time.

"On our entrance I noticed two gentlemen on the verandah, one of whom proved to be the landlord. We had not been long in the sitting-room before we heard a knock at the door, a policeman making his appearance immediately after, who at once requested to know what I was (meaning if I was free or bond). I answered that I was a free man. He next asked if I had anything to show for it. On this I produced my certificate of freedom, which satisfied him at once. I treated him to a glass of brandy, after which he excused himself by saying that one of the men who was standing in the verandah was no other than the district constable (Mr. Jones) who instructed him to make the before-mentioned inquiries.

"On the following morning I presented one of the £5 cheques which I received from "Gentleman Jones" (who had purchased the cattle on the Namoi) in payment of my bill. The landlord, after examining it for some time, returned me the change, and having remained that day and the next, I changed the other £5 cheque also, and on finding that the landlord kept a general store, I purchased wearing apparel and other necessaries to the extent of £50, presenting a £150 cheque in payment. He examined this with greater minuteness than the others, wishing to be informed how it was that there appeared to be two different handwritings on the face of the cheques, observing that the amount on all the cheques which I had presented was evidently filled in by a lady. I accounted for this by telling him that the lady who filled up the cheques resided with "Gentleman Jones", but in what relation she stood to that gentleman I could not attempt to say. Not appearing to be satisfied with this explanation, he observed that if I wished he would send it to the bank, but I would not agree to this, telling him that I knew where I could get it cashed in a moment. He then suggested that as there happened to be a son-in-law of "Gentleman Jones's" (a Mr.———) keeping a public house at Gorman's Hill, within one mile from Bathurst, he would send for him if I had no objection, and if that gentleman vouched for the correctness of the cheque, he would cash it in a moment. To this I consented, and in the course of an hour Mr.——— arrived, and at once pronounced the cheque genuine. He therefore gave me a written order on the Bank at Maitland, on presenting which the cashier commenced counting the notes. I told him that as I did not believe they were current in all parts of the colony, I preferred gold, but I had to take it in silver, and my companion indulged in a laugh on seeing the bag that contained it."

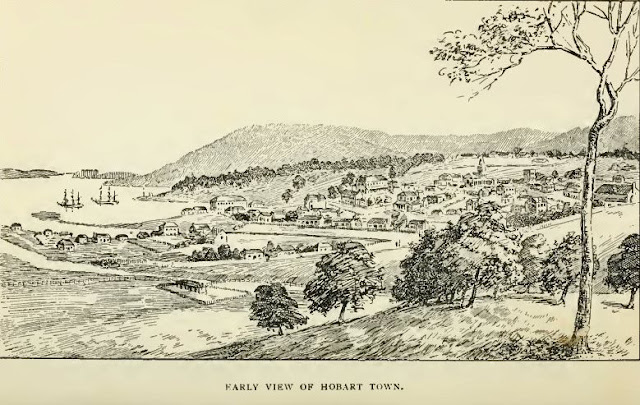

From Bathurst Cash made for Goulburn, and soon got an engagement as dairyman under Captain Sturt, the famous explorer, on his Mittagong station: but quarrels with a new overseer forced him to throw up this job, and he started for Sydney with a view of taking ship to Hobart Town. Near Camden he narrowly escaped arrest by knocking down the constable who stopped him, but reaching Sydney in safety he secured passages to Hobart Town (£20 for himself and Mrs. Cash, £5, exclusive of fodder, for his horse), and arrived in the island early in 1837.

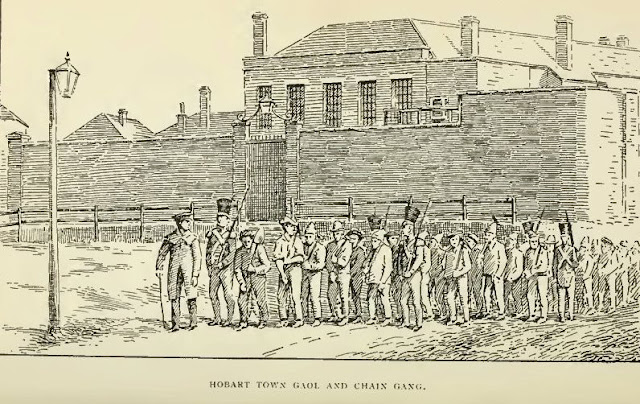

Within twelve months of setting foot in Van Diemen's Land Cash's troubles commenced. On two occasions he was wrongfully charged with theft; and, although the first case against him broke down, lie had beaten the arresting constables so badly that he became a "marked man". When brought up on the second occasion he was convicted and sentenced to seven years' transportation to one of the penal settlements, some distance from Hobart Town. But he had not been there more than a day when he effected his escape, having been sent out with a road-making party to draw stones in a handcart. Choosing a suitable spot and a favourable opportunity, he slipped away from his companions and hid in the bush until darkness had set in, when he started on his way back to Campbell Town, where he had left the disconsolate Mrs. Cash. During the night he stealthily entered the kitchen of a settler, appropriated a quantity of provisions, and pursued his journey until daylight, when, turning off into the bush, he was in the act of cooking some of the victuals at a fire he had kindled, when he was pounced upon by three soldiers and retaken. For thus escaping he was subsequently brought before the Police Magistrate at Oatlands, and received an additional sentence of nine months' hard labour in a chain gang, and nine months in a road party.

While in gaol awaiting transit, Cash formed the acquaintance of a fellow convict, to whom he unfolded a plan of escape; but the expected opportunity did not present itself until some time after he had arrived at his destination, and as his custodians had received a report concerning his previous attempt at flight, he was subjected to stricter surveillance than the other prisoners. For greater security he was leg-ironed with a pair of seven pound cross irons, and placed in a barrack, surrounded by a stockade twelve feet high. But he was equal to the emergency. Although within sight and hearing of a gang of billeted hands, who were working in the yard, he seized his opportunity, procured a goodly sized stone, and resting the centre ring connecting his leg irons upon another stone, struck and broke it, thus disconnecting the irons, although each leg still retained its separate adornment. Fastening the chains about each leg beneath the knee, he was prepared for action. The fitting moment arrived when the billeted gang left the yard for "grub", and seizing two night tubs that were lying near he placed them end on end and mounting managed from this perch to spring and catch the top of the palisade with his hands and drag himself over into the public thoroughfare. It was past 3 o'clock, and midwinter, so nobody observed his descent into the street, and walking quietly away he gained the bush, where he hid until darkness had set in. Late at night he broke into a mill and obtained a supply of provisions, then walking on till dawn, when he camped in the scrub and spent the day getting rid of his irons. Near Springhill he stole a good outfit of clothes, abandoning his prison suit, and so was able to make his way less cautiously to Mrs. Cash, at Campbelltown. They determined to leave Tasmania for Melbourne as soon as might be: and, with a view to raising the necessary cash, betook themselves to the Huon, having many narrow escapes by the way.

In this district Cash and his escapades were unknown, and after a steady year's work the money was saved. But Justice was not to be baulked so easily of its prey. They were detained a day or two in Hobart, Cash was recognised, seized by six constables, and again lodged in prison. Tried on the charge of absconding, his twelve months' honest work was put down to "cleverness". "But," said the presiding magistrate, the well-known John Price, "you will not best me, Martin" and he got two years added to his original sentence, and four years at Port Arthur besides.

What Port Arthur meant will be known to all readers of Marcus Clarke. Cash, however, was comparatively well off; he was strong and able to do all the log-lifting imposed upon him, and so did not come under the displeasure of the brutal overseers and sub-overseers.

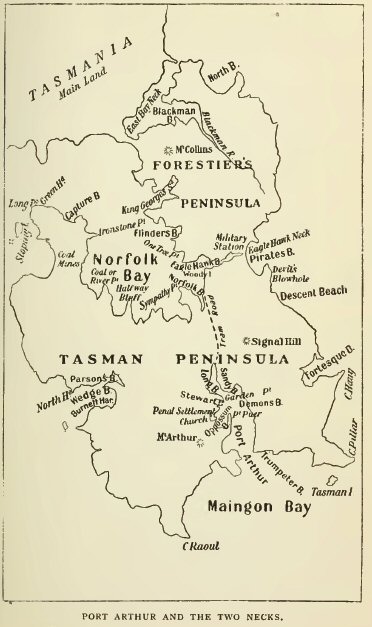

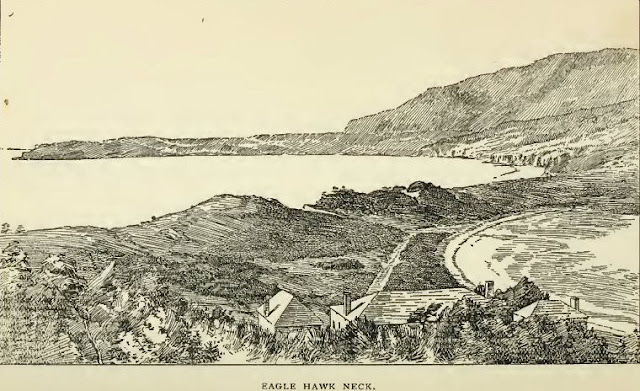

Still, he determined to escape—not immediately, for it was midwinter—and took every opportunity of learning the bearings of the land; particularly he marked Eagle Hawk and East Bay Necks, the two strips which must be crossed in order to reach the main land, and which were guarded by armed sentries and chained bloodhounds posted at equal distances along them. But his movements were accelerated by the harsh treatment of a sub-overseer; he knocked the man down, threw him over a steep bank into Long Bay, and made a start for liberty. After a night and a day in the bush he swam the inlet at Eagle Hawk Neck, but lost his way soon after, and five days after bolting was captured, half starved, within a mile of the second Neck. When brought before the commandant, O'H——a B——h, he escaped the lash by assuming a very penitent attitude, but was sentenced to eighteen months' hard labour in chains, and sent to work in a stone quarry with other ironed prisoners. Here he met with two men, Kavanagh and Jones, who had been transported for robbery under arms, committed near Sydney; and the three plotted a scheme for simultaneous flight. These new comrades of his relied greatly upon the man who had already proved his ability as an absconder, and said they would trust implicitly in his guidance when once they set foot upon the road to liberty.

On the afternoon of Boxing Day Cash, who was one of a gang that drew the stone carts, walked across the quarry and looked steadily at his two mates. At once they dropped their picks and sprang into the scrub, followed by Cash himself. Almost as soon as they started their absence was discovered by the sentries; a hue and cry was at once raised, and the rest of the gang placed under strict guard, while as many soldiers as could be spared set about searching for the runaways; the semaphore signals were also kept in full play, so as to put all the sentries on their guard. Having picked up a bundle containing some provisions, which had been placed conveniently for them by one of the cooks on the settlement who had been let into the secret, the trio made their way through the scrub to the foot of Mount Arthur. Here they hid for three days, hoping that by that time the sentries at the Neck would have relaxed their vigilance. On the third night they left their hiding place, and worked their way northwards through the scrub, often on hands and knees for a mile at a time, till their clothes were torn to shreds. At dusk next day they came in sight of Eagle Hawk Neck, and saw that the line was literally ally swarming with constables and prisoners. They concealed for three hours waiting for the coast to become clear, and then, with some trouble, swam the inlet, as Cash had done before, but when they reached the further side each one was stark naked, the clothes having been washed from their heads by the waves which had buffeted them in crossing.

Travelling without boots over rugged ironstone ridges and forging through prickly scrub without clothing to protect the body, were not pleasant exercises. Cash, therefore, led his mates to a roadside hut which he had noted on his last bolt, and fortunately reached it when the soldiers and prisoners were absent, except one man, who acted as cook. They made a simultaneous rush, Kavanagh arming himself with an axe which was standing at the door; the cook, seeing three naked men enter, completely lost his head, and before he could recover his senses was seized and securely lashed to one of the centre posts of the hut. They then helped themselves to clothes, of which there was an abundance, belonging to the prisoners who were away at work, as well as to a quantity of flour, beef, tea, sugar, and a flint and tinder box, and departed.

Knowing that this last enterprise would give their pursuers a clue to their whereabouts, and that a double watch would therefore be kept at East Bay Neck, they decided to conceal themselves for three or four days. During this time they had a very narrow escape from recapture, as a party of soldiers passed within a few feet of the spot where they lay concealed; and a little later on they nearly walked into the camp of one of the parties in pursuit. Creeping towards the neck, however, on the third day and hiding in the bush until nearly midnight, when only a few sentries remained on duty, they took off their boots, crawled past one of the sentry boxes, and got over the line into a paddock of wheat on the other side, through which they again crawled to the dense bush beyond. At last they breathed freely. "If I had a crown of gold," said Jones to Cash, "I would give it to you." "A little of it in my pocket would be more useful", said Cash, sardonically. Then for three hours they skirted the bay—on the right side of it now—and at the first halt, dropped sound asleep till long after sunrise.

Next day when Kavanagh put the question what was to be done, Jones answered, "Take up arms and stand no repairs", and to this they all agreed, though the decision meant certain death if they were ever caught. Their next move, therefore, was towards the more settled districts in the valley of the Derwent. At Pittwater they obtained provender from a hut, and proceeded towards Jerusalem, securing on their way a couple of guns, with ammunition, and some decent clothes. At Jerusalem a third gun and more provisions were obtained, and a complete outfit of clothes for each of them at the Bagdad public-house. Still making westward, they stuck up a farmer's house at Broadmarsh, and then camped for a few days to prepare for more serious business. They now decided to attack the Woolpack Inn, about ten miles from New Norfolk; but before reaching the place they fell in with a convict shepherd who told them that they would encounter an armed party at the inn, as a party of constables were stationed there. To this Cash replied that an encounter would suit them very well, as it would give them an opportunity of proving their arms.

Having planted their swag about a quarter of a mile away, they took the nearest road to the inn, and immediately "bailed up" the landlady, her two sons, and three men who were drinking there. While dealing with them people were seen moving outside; these proved to be the advancing party of constables, who had been made aware of the presence of the three desperadoes. The latter at once marched outside the house, Cash taking the lead. The leader of the party challenged Cash to stand. He stood, but only to take surer aim, and the challenger fell. There was an exchange of shots, but the darkness prevented any proper aim, and no damage was done on either side. Kavanagh and Jones now retired without acquainting their leader of the fact, and when he turned to speak to them he found that he was alone. He then retreated to the house, the constables apparently not caring to follow, and having secured a keg of brandy got out into the darkness and started for the spot where the swag had been left. Here he found his two companions; and after holding a "council of war", and testing the quality of the brandy, the gang retraced their steps to the Dromedary. Three days later, after pillaging a farmhouse for provisions, they reached the house of an old acquaintance of Cash's, who entertained them on the best and promised to take a message to the town for Mrs. Cash, who was residing there. On the way they learned that two of the constables had been seriously wounded by their fire, but not fatally.

Next morning the promise was fulfilled and Mrs. Cash joined the party, who had in the meantime made a kind of fortress of logs for themselves on the top of the Dromedary. For three days they remained quiet, and then set out to make a raid upon a large establishment owned by a Mr. Shone. On the way they fell in with a friend of the family, whom they compelled to go with them, and having obtained entrance to the house (the door having been opened to the voice of their prisoner) they immediately ordered the occupants, among whom were some ladies, to sit upon the floor. Six or seven working hands belonging to the establishment were also brought up from an outhouse to keep the owner and his family company, and two young ladies and three gentlemen who drove up in a vehicle on a visit were also, much to their surprise, placed "under cover" with the other prisoners. Kavanagh kept guard over the imprisoned company while Jones ransacked the house—"it being understood," says Cash, "that the professional process exclusively belonged to him"—and Cash watched outside. Before the bushrangers left the ladies and gentlemen in the room were relieved of their watches, jewellery, and purses; but the young ladies were not at all alarmed, having heard that Cash and his mates were very considerate in their treatment of the "weaker vessels" who chanced to fall into their hands, and being now in a position to personally test the accuracy of the report. Taking a respectful leave of their victims the bushrangers marched off, carrying their booty to what they termed their fortress. They literally loaded Mrs. Cash with silk dresses and jewellery from the store which they had so readily acquired.

For three days the party remained at the fortress, and then learned that a detachment of H.M. 51st King's Own Light Infantry under Major Ainsworth were scouring the bush in search of them. They then decided to remain in hiding for a few days longer; and in order that Mrs. Cash might not be exposed to danger in case of an attack they escorted her part of the way into the town and then left her. But the police were on the watch, and she had not been long in town before she was arrested on a charge of receiving stolen property, some of the articles belonging to Mrs. Shone being found in her possession.

Meanwhile the outlaws were not idle. They found shelter for a time at the house they had visited before, and from here they made two or three sorties upon residents in the district. One of the places "stuck up" by them was Mr. Hodgkinson's, that gentleman being at home with his wife and daughter (described by Cash as "a very pretty young woman about eighteen years of age") at the time. Before searching the premises they tied the old gentleman, although they admitted afterwards that there was more need really to tie the old lady, who persistently endeavoured to get out of the house, the while giving the robbers "the length of her tongue". At the request of Miss Hodgkinson they set her father at liberty, but this did not satisfy the mother, who made attacks upon Cash, and when the three were leaving she followed them and kept screaming after them until they were clear out of sight of the farm.

A few days afterwards they attacked the residence of Mr. Charles Kerr, in the Hamilton district. On the morning of their arrival they secured two of Mr. Kerr's shepherds, who gave them the necessary information concerning their master's premises, number of hands in his employ, together with similar information concerning other neighbouring settlers. Going up to the house with these two men about dusk they were met by a young lady, who immediately ran back crying "Here are the bushrangers", and then fainted. Leaving Kavanagh in charge of the men in the kitchen. Cash repaired to the drawing-room where he found Mrs. Kerr and the young lady, whom he urged not to be alarmed, as they should not be subjected to any insult. At Cash's request Mrs. Kerr pointed out the men's hut, and Cash and Kavanagh went there to find Mr. Kerr and three working hands. Kavanagh ordered one of the men to tie the others, but not liking the manner in which he performed his work he did the tying business over again himself, having to threaten Mr. Kerr before he would submit to the indignity. When the whole of the occupants had been placed in one room, the robbers released Mr. Kerr and permitted him to sit down in the room, and Jones, having produced writing materials, wrote the following letter to his Excellency the Governor:–

"Messrs. Cash and Co. beg to notify his Excellency Sir John Franklin and his satellites that a very respectable person named Mrs. Cash is now falsely imprisoned in Hobart Town, and if the said Mrs. Cash is not released forthwith, and properly remunerated, we will, in the first instance, visit Government House, and beginning with Sir John, administer a wholesome lesson in the shape of a sound flogging; after which we will pay the same currency to all his followers.

"Given under our hands, this day, at the residence of Mr. Kerr, of Dunrobin.

"CASH

"KAVANAGH

"JONES.

"His Excellency the Governor."

It thus appeared that the gang had become aware of the fact of Mrs. Cash's arrest. At the same time they wrote and signed the following note to Mr. Shone:– "Understanding through the public press that Mrs. Cash is in custody for some things you have sworn to, we hereby give you notice that if you prosecute Mrs. Cash we will come and burn you and all you have to the ground." These letters Jones read to the imprisoned company, and then the gang gathered up the valuables in the house and took their departure, Mr. Kerr urging them to give up their evil ways, and offering to intercede on their behalf with the Governor; but they replied that they thought their letter would be a powerful appeal on their behalf, and Mr. Kerr's kindly offer in this direction was politely declined. They left the letters with him, however, to be forwarded to their destination.

Two more attacks on stations in the Hamilton district brought them in so much spoil that they determined to rest awhile at their friend's house under the Dromedary, where they had an old Irish fiddle: to play to them.

Meanwhile the police were actively searching for them, but without success. In addition to a pecuniary reward offered for the apprehension of the outlaws, the Governor offered a free pardon and a free passage from the colony to any convict who might be instrumental in their capture. The state of alarm into which the community had been thrown was great. Even the officials not actively engaged in the hunt were in fear, as may be gathered from the following paragraph which appeared in the Hobart Town "Advertiser":– "So universal has been the panic among the police that the acting police magistrate, living in one of the most populous towns in the country and at a distance of several miles from the scene of their depredations, has actually applied for a military force for his own particular protection, fancying, as he alleges, that he may be carried off and obliged to pay ransom." The same paper, of a later date, contained the following:– "The perfect insufficiency of the police to apprehend Cash and his troupe is at length acknowledged, after some months' unavailing efforts. The military have been in consequence ordered to their assistance. Thirty-nine men, under the command of Lieutenant Doreton and Mr. Stephenson, have been ordered to occupy several posts in the district which has been the scene of their daring exploits. Here, stationed at different points, they may intercept them in their progress when necessity compels them to leave their haunts, which the knowledge of the locality renders secure while they choose to remain in seclusion. We have no doubt that these measures will prove successful."

While this arrangement was being made the gang were contemplating an attack upon Mr. Edols' establishment, at the Bluff. They had heard that a party of soldiers and police were stationed at the place and appeared desirous of putting the prowess and bravery of the detachment to the proof. Accordingly they watched the place for some time and having (after the plan usually adopted by them) intercepted one of the men servants and obtained from his not unwilling lips a full account of the strength of the inmates, they made arrangements for the descent, taking the man with them as a guide, and threatening him that if they did not find his story true in every particular they would "send him to sleep with a bullet in his brain." The man told them that the first obstruction they would meet with on the premises would be a very savage dog; and sure enough, as soon as they entered the gate a large mastiff flew at them. Cash met the savage animal, and as it sprang open-mouthed at him, he drew a pistol from his belt and rammed the muzzle down its throat, at the same time pulling the trigger. The dog fell dead at his feet. The members of the gang were in momentary expectation of being fired upon from the house, and they made a rush at once for the verandah. Knocking at the door of a room in which they observed a light and receiving no answer, they together burst the door open and entered the room to find Mr. Edols and his two nephews (young men) sitting there with the ladies of the household, in a great state of alarm. On looking behind the door Kavanagh found three stand of arms all loaded with ball, and subsequently Mr. Edols was found to have about his person a pair of duelling pistols. After twitting their victims with their want of pluck, the gang broke the firearms, being afraid to discharge them on account of the noise they would make, and proceeded to help themselves; then bidding the ladies good night they left the place, and retired to their "fortress".

They now struck northwards across Constitution Hill, but in a few days grew tired of idleness—though Cash seemed to have enlivened things with a discourse on the vanity of human wishes, which made Jones declare that mouths were made for eating, not for jabber. Presently they came into open collision with a magistrate in the bush. Just before this Cash had coolly walked into a public house bar in Greenponds, at which several persons were drinking and purchased two bottles of rum; but although the inmates eyed him suspiciously, and a constable looked in at the door, he was not recognised, and an hour afterwards he had rejoined his companions and was rehearsing the scene to them. The magistrate, whose name was Clark, was riding towards his residence, having as a follower one of his assigned servants, armed, but on foot; and as soon as they came near the party Kavanagh ordered the man to drop his gun, which command was promptly obeyed, and master and man were then detained by the gang and compelled to accompany them to an adjoining farm, which they were about to "stick up"; Cash observing to the magistrate that he would give him a lesson in the art of robbing and then set him at liberty. On the road they met two other men, who were also compelled to go with them. They found the premises (Allardyce's) in charge of an overseer, whom they at once secured, together with the workmen, and having driven them all into a room with the other inmates of the house, they proceeded to ransack the place. Before they left Clark requested Cash to allow him to go to the Governor and sue for terms, but the outlaw declined, saying that when Sir John had them in custody he might dispose of them as he thought fit, but that while they lived they would not ask any favour at his hands.

Having replenished their store of provisions the gang made for the Shannon, and for about a fortnight their chief pastime was firing at targets marked on the trees; Cash declared that he "seldom failed to place a bullet in the circle at a distance of 180 yards and further." Soon the party were ready for fresh exploits; and so we find them creating a sensation near Lake Echo, "sticking up" the settlers, and even making a successful raid upon the establishment of Captain McKay, who was renowned as a very determined soldier, and a vigilant hunter of escaped criminals. As usual they first visited one of the huts and obtained from a shepherd full particulars of the place and the habits of "the master", and then took the man with them to prevent him raising an alarm. On the way to the house, they fell in with a settler named Gellibrand, whom they also took along, making him go forward and gain entrance for them. Captain McKay and his servants were speedily placed under guard, and the gang set to work to "entertain" them, liberally handing round spirits and tobacco among the assigned servants, who were strangers to such luxuries; when McKay protested he was reminded that he was not now in command—"We're in charge now," said Kavanagh, "and I'll shoot the first man who leaves off smoking." Having "looted" the house they loaded two of Mr. McKay's horses with the booty and marched their prisoners to Mr. Gellibrand's, where, after a short delay, Cash gently upbraided his captive host with lack of hospitality, and so secured an invitation to tea for the whole band. McKay was placed at the foot of the table between two of his own men, much to that gentleman's discomfiture. Only Cash's firmness, however, saved him from a worse fate: for Jones was very anxious to flog him as cruelly as he was wont to flog his servants—a retaliation, said Jones, which he had found to work well in New South Wales. Before leaving the place with their "takings" the gang stripped the whole party of their boots, in order to prevent them from following them or giving the alarm to others. They then speedily made their way back to their old camp under the Dromedary, and sent in all haste to Hobart for their fiddler. While here Cash learned from the papers that Mrs. Cash had been released by the Governor, and he flattered himself that this was the result of the threatening letter he had sent to his Excellency shortly after the arrest of that lady; but the truth of the matter was that she had been liberated in the hope that some clue to Cash's movements might be obtained through her, and that he might be even induced to visit Hobart Town if he learned that she was living there in freedom. As will be seen farther on, this ruse proved successful.

The next exploit of the bushrangers calling for notice was an attack upon the residence of a well-to-do settler named Kimberley, near Broadmarsh. On reaching the house they found the door barred and the inmates in bed, and as their demand for admittance was not promptly answered, Kavanagh shot the lock off the door and the three men entered. The first thing Cash saw was a man trying to escape through the window: he tried to drag him back, but the man's belt came loose in his hands, and in it Cash found fourteen rounds of ball cartridges. Mr. Kimberley was found in bed in another room, with a loaded gun standing near at hand; he meekly rose when ordered, and was led into another room, where four others had already been placed. Kavanagh stood guard over these while Jones proceeded to further search. Coming to a door that was locked he applied the muzzle of his piece to the lock and was about to fire when Cash made him desist, saying he heard female voices in the room. Mr. Kimberley then called out that his three daughters were in the room, and then Cash told them not to be alarmed, but to dress quickly and come out. This they did, and having been transferred to Kavanagh's keeping, they had to look on with the others while Cash and Jones ransacked the place.

Leaving Mr. Kimberley's they went off to the hut of a friendly convict, left their knapsacks outside, and sat down to supper. Suddenly they heard a voice outside saying "Surround the hut; we have them; here's their swag." A party of soldiers and constables—ten in all—had at last come within reach of the outlaws. On hearing the exclamation Jones at once blew out the light, while Cash seized his gun, opened the door and fired both barrels right and left, at the same time shouting "Come on, my hearties; you have got us!" There was no response, and Cash returned to the door and reloaded his piece, Jones asking what should be done. "We'll have to shoot two or three of them", said Cash, and stepping outside again he loudly inquired if they were all dead, at the same time reminding them of the large reward they would get for capturing them, if they were only brave enough to try. At this time there was a reward of £150 on the head of each of the bushrangers, with 100 acres of land and a free pardon, if the capturer happened to be a convict. The three now advanced together about fifty yards from the hut, but could not see their assailants. At last they heard the soldiers at the hut calling upon them to surrender; they fired, and the soldiers returned their fire; one ball grazed Cash's ear, but did not wound him; but it was too dark to aim straight, and the soldiers sought shelter in the hut. The bushrangers challenged them several times to "come out and fight like men", but they contented themselves with firing from their shelter, promptly answered from the darkness outside. At last Cash and his mates began to think about retiring, but did not care to go without their rugs and knapsacks; Cash accordingly crept up to the hut, but could find only one rug, which he at once carried back to his mates; and all three then made for the Western Tiers, where they camped.

A few days afterwards the gang took a new departure, and bailed up the passenger coach at Epping Forest. There were a number of passengers in the coach at the time, including several ladies, but one of the first things the bushrangers did, after stopping the coach and telling the passengers to alight, was to assure the ladies that they were "not the men to hurt women." They emptied their purses, nevertheless, in common with those of the male passengers, and then allowed the coach to proceed, themselves making across country in the direction of Ross, where they varied the entertainment by attacking the residence of Captain Horton, which was near the troopers' quarters. Mrs. Horton escaped through a window and ran into Ross to give information to the authorities, but the soldiers arrived only to find that the birds had flown.

During the next week Cash and his mates kept quiet in the fastnesses of the Western Tiers, and it was when starting from his hiding place bent on another raid that an event happened which led to the break-up of the gang. When travelling over some very rocky ground Kavanagh fell, and his gun exploded, the ball entering his arm at the elbow and coming out at the wrist. It was decided to return towards Bothwell, in the hope of obtaining surgical assistance from the township, as Kavanagh's wound was a very serious one. Cash's plan was to find out where the doctor lived, and march him off in custody to attend to his wounded mate; but the letting of blood appears to have deprived Kavanagh of some of his bravery, and before this plan could be carried out he determined to surrender himself to Mr. Clark, at Cluny, an old acquaintance. Nothing that his companions could do or say was effective in shaking Kavanagh's determination, and finding that he was not to be moved from his purpose, they accompanied him within a short distance of Cluny and then left him.

Speaking of this affair. Cash subsequently wrote: "I am sorry truth obliges me to say that Jones, while on the road to Mr. Clark's, privately hinted the necessity of shooting Kavanagh, being under the impression that he might reveal our haunts. I rebuked him for making such a heartless proposition, observing that had I been in Kavanagh's situation he would treat me in like manner, and regretting very much to hear him suggest anything so unmanly, I kept my eye upon him until Kavanagh was far away on the road, being of opinion that Jones would do almost anything rather than forego his visit to Mrs. B——n's at the Dromedary. We returned in very bad spirits, as neither of us liked the idea of Kavanagh giving himself up to the authorities, although I never for a moment thought that he would make disclosures to injure us. For the first time I now became disgusted with my calling, being of opinion, after what had lately transpired, that there could be no confidence or friendship between men placed in our position. But the die was cast, and I was obliged to follow it up to the end."

After leaving Kavanagh, Cash and Jones made their way back to Mrs. B——n's house at Cobb's Hill, half fearful that their former retreat would become a trap, as it would undoubtedly have done if Kavanagh had "split" upon them. But they found everything as it was before, only their friends being in the house. Cash, however, became suspicious, and could not make up his mind to stay long. It was while waiting here that they planned one of their most successful robberies. Hearing that a Mr. Clark, of the Tea Tree, had about £200 in the house they determined to make a raid and possess themselves of that treasure; and under the guidance of one of their friends they made their way to the place. Entering the house suddenly they gave the inmates no time to make resistance; and almost before the astonishment created by their visit had subsided they had disappeared again. On the same night they bailed up the mail coach at Spring Hill, relieving the driver and the passengers of all their money, watches and jewellery, and the mailbags of all the letters having the appearance of containing money. They also helped themselves to the latest newspapers, intending to learn all contained therein concerning the movements of the military and constables, who were now accompanied in their researches by black trackers.

At last Cash determined to visit Hobart and look after Mrs. Cash, about whose conduct malicious rumours had been spread. He arrived safely in town, looked up his friend the old fiddler, and started with him to find Mrs. Cash's house: but unfortunately he was compelled to ask directions of a man in the street. The man at once pointed out the house, but at the same time called out to another man standing near, "This is the party we are looking for", at which Cash made off, the two men following him, firing at him as he ran. The remainder is thus told by the Hobart Town "Review":– "By this time a number of persons had joined in the pursuit, and the alarm increasing, a man named Cunliffe, a carpenter, came from his house as he passed, and lifting his hand Cash discharged his pistol, which wounded Cunliffe in the fingers. Cash then crossed Elizabeth-street and ran along Brisbane-street, making for the paddock, and as he passed the public-house called the Commodore, opposite Trinity Church, one of the Penitentiary constables, named Winstanley, seized him. A struggle ensued, when Cash drew a pistol and shot him through the body: he died the next day. A person named Oldfield coming up, Cash fired at him, wounding him in the face. At this moment another man tripped him up, and a number of persons arriving he was handcuffed, but not until he had made much resistance, in the course of which he was much beaten. He was then taken to the Penitentiary to be identified, but he was so disfigured in the struggle to capture him that Mr. Gunn could not then recognise him. He was, however, conveyed to the gaol, no doubt existing of his identity."

A week later the same paper contained the following:– "Cash and Kavanagh.—We have already furnished our readers with full particulars of the capture of these unfortunate men. They were both tried separately yesterday—Cash, for the murder of the constable (Winstanley); Kavanagh, for the robbing of the Launceston coach. Cash was defended by the late Attorney-General, Mr. Edward Macdowell, who, although evidently labouring (we sincerely regret to say) under severe indisposition, yet defended the unhappy man with his usual zealous judgment. The jury found both prisoners guilty, but a point of law, as to whether Winstanley knew Cash to be a proscribed absentee when he met his death—whether the melancholy event, deplorable as it was, could be wilful murder, a chief element of which is malice prepense, and on some other subjects, is reserved for the decision of both judges."

Cash had walked into the dock in the most unconcerned manner, and stood during the trial with his arms folded. He was dressed in blue jacket and trousers, and blue striped shirt, a black handkerchief round his neck, and a green one round his head to cover up the wounds he had received at the time of his capture. The indictment against him was drawn up in the usual elaborate manner, charging him "for that he did, on the 29th August, with a certain pistol of the value of five shillings, being then and there loaded with gunpowder, which gunpowder exploded and discharged a leaden bullet, which did strike, prostrate and wound the left breast of the said Peter Winstanley, of which wound he died on the 31st August." Neither Cash nor Kavanagh made any defence for themselves, except to say that they had never shed blood where it was not absolutely essential to their own safety—a statement which the judge admitted to be true. On conviction they were removed to the cells to await execution, but two days before the time arrived they were informed that the sentence of death had been commuted to transportation to Norfolk Island for life. The intelligence of their respite was conveyed to them by Rev. Father Therry, to whom Cash had taken a great liking, and a few days afterwards the two men, with twenty-two other convicts, were placed on board the brig "Governor Phillip", and conveyed to their new destination. Here Kavanagh was hung within a year for joining in a mutiny; Cash, however, after many ups and downs, and (if we can believe his own story at all) a great deal of petty persecution from Commandant Price*, managed to escape the utmost penalty. Through the instrumentality of the commandant who succeeded Mr. Price, a petition for a remission of his sentence was favourably received. He served for a time as constable at the Cascade, and having married a convict servant of the resident surgeon on the island, he went back to Van Diemen's Land when the establishment at the island was broken up. Here for a time he served as caretaker at the Government Gardens, and subsequently went to New Zealand, where he managed to accumulate a little property. After residing in the land of the Maori four years he returned to Tasmania, and purchased a farm at Glenorchy, near Hobart, where he passed the remainder of his days "in the calm and tranquil enjoyment of rural retirement."

[* With reference to the alleged petty persecution of Cash by Commandant Price at Norfolk Island, the following statement on the other side is of interest, I took it down from the lips of the late Mr. Frank Belstead, Secretary for Mines, Tasmania, who was a young officer under Price at Norfolk Island when Cash was there:–

"When Martin Cash was reprieved he was sent to Norfolk Island. Major Childs was the Commandant, but he was shortly afterwards superseded by Mr. Price. Soon after Price's arrival he sent for Cash. Cash came to the office. I was present and heard all that passed. Price, after his manner, called Cash by his Christian name and chaffed him. He said: 'Well, Martin, so you're here, and I hear that you're going to make a long stay?' 'Yes, Sir' said Martin. 'Well,' said Price, 'I know all about you, and if you'll act on the square I'll lay up to you.' He went on: 'It's a bargain, is it?' 'Yes, Sir,' said Cash. 'Well,' said Price, 'remember that if you make a mistake I'll come down on you just as I would on anybody else; but, if you conduct yourself, I'll give you every chance.' 'Thank you, Sir', said Cash.

"In a very short time Cash was made a sub-overseer. This gave him the privilege of sleeping in a hut, instead of being locked up in barracks with the ordinary prisoners at night. He had tea and sugar and could smoke if he chose—a great privilege on Norfolk Island, though I think Cash was not a smoker."

Mr. Belstead then narrated the various steps of promotion which Cash got at short intervals, and concluded by saying:–

"Cash conducted himself well, and Price kept his word to him, granting him every indulgence that the regulations allowed, (ash had not the least reason to complain of his treatment, and the statements he has made in his "Life", respecting Price's harshness and cruelty to him a re entirely without foundation in fact."

Jones, who had evaded capture for about seven months after his leader had been captured, met his death on the scaffold—a fate apparently due to his own ferocity, which Cash had so often restrained. After Cash had left the "Retreat" for Hobart Town, Jones took up a fresh position on the Dromedary, and formed a new gang with two runaway convicts. During one raid a woman refused to tell where money was secreted, and in order to make her confess Jones tied her up, gagged her, heated a spade in the fire, and applied the red-hot iron to her legs, causing terrible injuries. On another occasion he deliberately shot a constable who was in pursuit of him, and subsequently boasted of the murder. Shortly after this, however, the woman at the "Retreat", Mrs. B———, fearful for her own safety, gave secret information to the authorities, who set a watch and trapped the whole party of bushrangers in the hut of a man who had been harbouring them on the Dromedary. Moore, one of the gang, crept outside the hut on his hands and knees, and was immediately shot by one of the constables. Jones came out next, and received a heavy charge of shot in the face, which blinded him, rendering his capture an easy matter. The other bushranger, Platt, was taken without being injured. Then followed trial, conviction, and execution; and for some time thereafter the peace of the residents in town and country in that land of notorious bushrangers was undisturbed.

Sources:

Sources:

- The Bushrangers (1915, February 23). The Farmer and Settler (Sydney, NSW : 1906 - 1955), p. 7.

- The Bushrangers (1915, February 26). The Farmer and Settler (Sydney, NSW : 1906 - 1955), p. 7.

- The Bushrangers (1915, March 2). The Farmer and Settler (Sydney, NSW : 1906 - 1955), p. 7.

No comments