During four years the country rang with reports of their desperate deeds, to narrate which in detail would fill a volume. Cases of "sticking up" on the road or in houses were of daily occurrence. Settlers and others were robbed, completely stripped, and left in the bush to make their way home as best they could. Nor did the ladies even escape, for there were several instances in which it was related that the robbers had taken the earrings from their ears, and the rings from their fingers — these outrages being committed close to Sydney. They had frequent fights with the police, with results usually indefinite.

Here is a story told by one who subsequently became mixed up a good deal with crime and criminals, having been appointed a detective under the Government of both New South Wales and a neighbouring colony:—

"At this time I was in the employment of Mr. Wilfred, who had a station near Bringelly, about 30 miles from Sydney. One beautiful summer morning along with Mr. Wilfred I started from Bringelly, in a chaise and pair, driving tandem. I recollect that as we were about to leave, a gentleman connected with the Union Bank remarked, "Now, Mr. Wilfred, mind you do not fall in with those boys in the bush." "Oh, no fear," replied Mr. Wilfred, "I have travelled the road for years, and I have never met with a bushranger." But we know the proverb of how often the pitcher may go to the well before it is broken."

"All went well until we got about a mile and a half beyond Liverpool. This hamlet, which was dignified by being considered a township, and borrowed the name of the shipping metropolis of Britain, consisted then, whatever it may be now, of about a dozen little huts or shanties, inhabited by what were termed "Dungaree", or "Stringybark settlers." These people had a small patch of ground, on which they grew maize, and this grain constituted almost their only article of diet, for they considered it a luxury if they could obtain a few pints of flour in the course of a year to mix with the maize meal. They would indeed sometimes grow wheat, but they could not afford to consume it. They brought it to market, and one of the principal purchases which they made with the proceeds of the sale was a keg of rum, necessary for the annual rejoicing which they had at the end of harvest, when they drank the spirits from the pannikins, and for a few days the equanimity and monotony of their simple mode of life would be disturbed by unusual revelry. Well we had not got two miles past the settlement of this enterprising band of colonists, when in a piece of thick iron-bark scrub, at a sharp turn of the road known as Stamford Hill, we were stopped by three noted bushrangers mounted on horseback. One appeared on either side, and one a short distance in front, and each presented a fowling piece. Of course, resistance was out of the question; we were but two to three, and we were covered by their muskets. They ordered us to "stand", and we had no alternative but to obey. Mr. Wilfred then in obedience to their further commands, stepped out of the chaise, when they not only robbed him of his watch, money and jewellery, but also completely stripped him of his clothes, leaving him with nothing on save his shirt."

" "Now, Mr. Flunkey," said one of the worthy trio to me, "it's your turn." I was subjected to a close search, but as I had only a few shillings in my possession, they allowed me to retain the money, and I was anticipating that I would be permitted to go "scot free", when the attention of one of the men whom I afterwards recognised as Webber, was attracted by a pair of strong kip boots which I wore. They were colonial-made, and rare in those days, and were much prized by bushmen. "Oh," said Webber, just as I thought they were done with me, "but I must have his boots; they will just suit me." Accordingly, I had to denude myself, however unwillingly, of my envied boots, when Webber put them on, and declared them to be a "deuced good fit." "

"The chaise was next made the subject of their delicate attentions. As luck would have it, we had in the vehicle some twelve or fifteen pounds of powder, which we were taking to Mr. Lowe, a magistrate, who lived about two miles from Bringelly, to be used in duck and kangaroo shooting. The free-booters (the name seems specially appropriate when I consider how they treated my pedal coverings) were exceedingly pleased with this prize, which they declared was "just what they wanted"; and, having tied the whole of their plunder on their horses, they bade us good day, and disappeared, in the greatest good humour."

"I had to drive back to Liverpool and obtain some clothing for the denuded Mr. Wilfred, after which we continued our journey, and arrived with no further casualty at Bringelly."

A Mr. Eaton was proceeding from Sydney towards Liverpool on horseback when Donohoe or one of his gang fired at him from the side of the road and severely wounded him. After he had fallen two members of the gang robbed him of his money and valuables and a portion of his clothing and then decamped, leaving him bleeding on the road. Before nightfall, however, some settlers on their way to town picked Mr. Eaton up and carried him home.

Next day a young man who had gone up to inspect some cattle at Liverpool was deliberately shot in the neck and chest when on the road, and as Donohoe and Underwood were then in the neighbourhood they received credit for the outrage. No attempt was made to rob the victim, who was left lying on the road.

The "Australian", a Sydney newspaper, published the following paragraph about this time:

Donohoe, the notorious bushranger, whose name is a terror in some parts of the country, though we fancy he has more credit given to him for outrages then he is deserving of, is said to have been seen by a party well acquainted with his person, in Sydney, enjoying, not more than a couple of days ago, quite at ease apparently, a cooling beverage, derived from the contents of a ginger-beer bottle.

As a commentary upon this it may be stated that no less than six cases of "sticking-up" occurred on the Parramatta-road during the ensuing week.

So great became the alarm that travellers joined on the road for mutual protection, and a newspaper of the day offered the following comments:–

For the past few days there have been fewer instances of robbery than there were during the last week or two; yet travelling is far from safe — even between Sydney and Parramatta many persons rather than venture alone still jog along in sixes and sevens, or keep up, for protection, with the coaches. Some half dozen constables or so, we believe, have been packed off along the Parramatta and Liverpool Roads, but have returned to town, as usual safe and sound, but empty handed. Not so in Van Diemen's Land — when the bushrangers were playing their worst pranks, the Lieutenant-Governor himself set forth in search of them, and even now Colonel Arthur threatens to pursue the refractory aborigines in person through the island. But here, with a mounted police and a police establishment, which if not effective is not for want of expense, and a strong garrison of armed soldiery, the bushranging gentry seem to carry on their pranks almost without molestation. If the constables cannot be depended upon or spared in sufficient numbers, there is the horse-police; and surely out of 800 soldiers, 40 or 50 picked men might be dubbed constables, pro tempore, and despatched to scour the roads of those marauders who, though comparatively few and weak in number, by the comparative impunity they are allowed to enjoy, carry terror and devastation into the huts of the lonely settlers. Some effective measures should be taken, and that speedily, to suppress this alarming evil.

One evening in September, 1829, Donohoe and Underwood entered the hut on Sir J. Jamieson's estate, and having tied up the inmates proceeded to cook supper for themselves. Donohoe actually made preparation to burn the hut with its inmates, but was prevented by his companion from carrying out his cruel design. Going to the other extreme, he then forced the unfortunate victims in the hut to drink a large quantity of rum, and having further secured their hands and feet, the robbers walked off with everything they could carry.

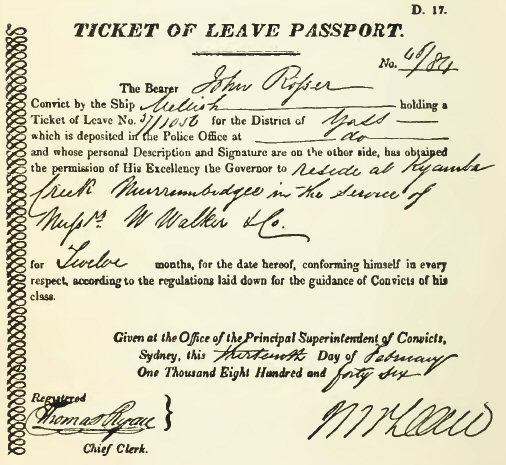

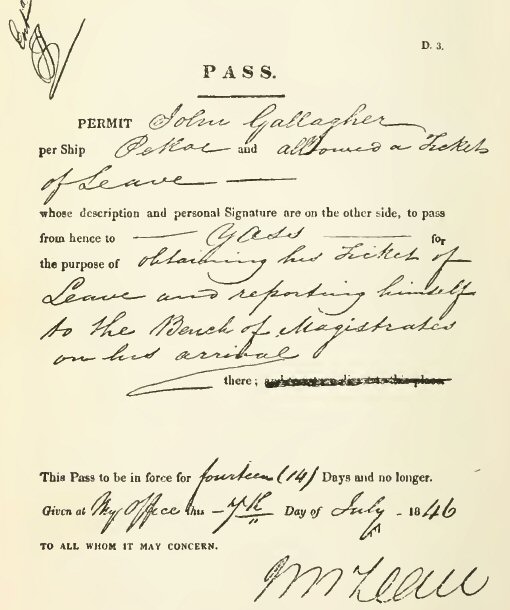

At this time a reward of £100 was offered by the Government for the capture of the two men. If the captor was a convict he would receive a ticket-of-leave as well as the money.

They then went up the mountains, well mounted and armed, Fish River and Mount York being reported as their camping grounds. Just at this time the Governor was making an official visit to Bathurst, attended by a strong body guard, and a hope was expressed that they would fall in with the bushrangers, but that hope was not realised.

The following is the full text of a letter written from Windsor shortly after the occurrence therein narrated took place:—

On Thursday, 14th instant, as two carts laden with divers property belonging to Mr. McQuade, shopkeeper, Windsor, were returning from Sydney, and when within two miles of Windsor three armed men rushed out from the bush and ordered the carters to stand. They pulled up, and then found the three men to be Donohoe, Walmsley, and Webber, the bushrangers. The bandits commanded them to drive into the bush about 40 rods, and arrived at the spot Donohoe questioned them as to the owners of the stores in the cart, and also sought information as to the movements of the chief constable and police magistrate of Windsor. Walmsley was then placed to keep the carters under cover while the other two proceeded to ransack the carts, making one of the carters assist. In one cart was a crate of earthenware, a large quantity of print and calico pieces, and two bags of sugar. The bushrangers removed all the print pieces, etc., but left the earthenware, and cursed the drivers for not having some tobacco on board. Donohoe said he would give all the rest of the stuff for half a basket of tobacco, and one of the carters innocently said "If you let me know where I shall leave you some I will in less than two hours deposit two pounds for you anywhere." Donohoe answered rather angrily "What a flat I am." Just then another vehicle was heard passing along the road, and Donohoe said if they were not busy they would bail up the occupants, but they could not do it just then. It subsequently transpired that the travellers were the Police Magistrate and Mr. Richardson, the surveyor. There was a crate of rum in one cart among the other things, and this Webber broached, the men expressing regret that there was not a small crock or keg to put the liquor in. Donohoe and Walmsley drank very little but Webber drank so much as to call forth a reproof from his leader, when he replied "I wish I could get some of this when under the gallows"; then Donohoe replied "I would rather meet my death by a ball than the gallows." Donohoe is represented as being lame in the left arm about the shoulder, but remarkably active nevertheless. On one occasion, rather than go round the cart he put one hand on the horse's rump and sprang to the other side with remarkable ease and agility. One of the three proposed to take a bag of sugar amongst the other articles, but Donohoe objected, saying that he would not be burdened: but he made one of the carters hold the bag while he cut it open and emptied some of the contents into a small corn bag.

They conversed rather freely with one of the carters, acknowledging that they had been harassed of late, and that they were very short of bread. In rejoinder to something the other carter said Donohoe assured him angrily that they were not afraid of the chief constable and all his bloodhounds, and dared him to send them all out after them as soon as he got into Windsor. "Tell him," said he, "to send us half a dozen flannel shirts, as the nights are cold; tell him somebody else knows the bush as well as him, and that we know he has been after us three weeks at a time; if you have any mind to keep any part of these things in the cart do so and lay it all on us and welcome, we've got enough." Boyle (the carter) turned all his pockets inside out to convince the bushrangers that he had no tobacco, and Donohoe, looking at the spirits, said, "D—— the rum; I'd sooner have a loaf or some tobacco than all the —— stuff." Quin, the carter, said that the affair would go hard with him, as he was only just free and would be made answerable for the goods. "Ah," said Webber, "What would I give if I were free!" Donohoe then made two packages of the fifty pieces of print and fine pieces of calico, and a third package of the sugar, and tied them with a strand of the cart rope so that they would fit over each man's shoulders and leave the arms free. They were all well armed, having each a brace or more of pistols slung before them, by leather belts around the body and holsters to hold them. In addition to the pistols Donohoe and Webber each had an excellent fowling piece. They all presented a remarkably clean appearance, and were dressed as follows:– Donohoe—black hat, superfine blue cloth coat lined with silk, surtout fashion, plaited shirt (good quality), laced boots rather worn at the toes and snuff coloured trousers; Walmsley—black hat, shooting jacket with double pockets, blue cloth trousers, plaited shirt and laced boots; Webber—black hat, blue jacket, plaited shirt, with very handsome silk handkerchief round the neck, blue trousers and laced boots.

After shaking hands with the carters the bushrangers rode away, Donohoe saying that if it were not for the large reward offered for him, he would go to Sydney, "fence the swag" and leave the country.

Quinn and Boyle immediately reloaded what was left into the carts and went into Windsor and reported the matter to the chief constable, who proceeded himself with the horse police in search of the desperadoes. Black Jemmy also went out and tracked the footsteps of three men until darkness came on. The constabulary then watched for fires during the night, but Donohoe was no novice, and doubtless travelled during the darkness and rested in the day. From the fact of the bushrangers being able to find a market for so much calico and print, there can be no doubt that they have some receivers, and consequently friends who supply them with comforts and information concerning the movements of the police.

So the game went on. Mr. Lawrence Dulhunty, who had helped to capture Mustin, was caught, and stripped naked in revenge, and narrowly escaped having his ears cut off. Mr. Blaxland, of Newington, was stopped in his own drive, and only saved from their brutal treatment by the bravery of his daughters. One day the gang would be heard of as robbing a traveller within a few miles of Sydney, and the next as having stuck up a store or station a hundred miles from the quarter where they had been last seen. Donohoe was, indeed, once arrested, but while being brought from the prison to the court, he succeeded in effecting his escape. A hero before in the estimation of the ignorant and tainted portion of the population, he was now regarded as possessing a charmed life. At one time he was said to be at the head of at least a score of bushrangers, and all the efforts of the constabulary to break up the gang proved unavailing.

At last the residents rose in their own protection. A number of gentlemen formed themselves into a corps to clear the country of the band of desperadoes, and they arranged and carried out their plans effectively. Wisely determining that it would be futile to chase the marauders through the country, the volunteers took post near Bringelly, which was one of Donohoe's favourite resorts. It was not long before the banditti paid a visit to this locality, and made their head quarters in a peculiar recess in the bush, which was known to their pursuers. Thither the volunteer corps, to the number of about a dozen, repaired, in the hope of being able to surprise the bandit camp. The feet of one of the horses, however, dislodged a stone, which, rattling down a precipice, alarmed the bushrangers, and they prepared to give their assailants a warm reception. Being about equally matched a sharp action took place, in which several men and horses on both sides were wounded, but none fatally. At length, the assailants, finding they could secure no decided superiority, feigned an attack, when the bushrangers fell back and the volunteers, taking advantage of the opportunity, turned and retreated, in order to obtain a reinforcement of mounted police who were in the neighbourhood.

Joined by the troopers, the volunteers renewed the fight. Both parties fought best under cover, concealing themselves behind trees and firing on any opponent who exposed himself. There was among them an old soldier, a good marksman, who selected the bandit chief for his victim. He watched for his opportunity when Donohoe was looking from behind the tree at which he had taken his stand, and fired on the instant; both the bullets with which the musket was loaded took effect in the bushranger's head. Their leader slain, the bushrangers took to flight, and most of them succeeded in effecting their escape. On the person of Donohoe there was found a small pistol, loaded, with which it was said he intended to commit suicide if at any time he should find escape impossible.

Walmsley and Webber, the other two leaders, held out a little longer, until the former, it is believed, betrayed his comrade. While they were in the act of sticking-up a gentleman and his carriage on the Western Road, they found themselves in an instant surrounded by a body of police who conveyed them to Sydney. Walmsley turned King's evidence against Webber, and caused great consternation among his old friends in the bush by giving full information as to how they disposed of the whole proceeds of the robberies. The houses of some thirty different people were searched and a large amount of valuable property was recovered. Webber was convicted and hanged, while Walmsley was transhipped to Van Diemen's Land. The receivers of the stolen property, against whom Walmsley gave information, were sentenced to various terms of imprisonment, and the reign of terror in the New South Wales bush was brought to a close.

Source: The Bushrangers (1915, March 5). The Farmer and Settler (Sydney, NSW : 1906 - 1955), p. 7.

No comments