The year was 1867, the year that the greatest floods of record hit New South Wales. From April reports started to filter in of devastating floods throughout the state. The worst were to occur in June 1867 in the Hunter (Maitland and Newcastle), the Hawkesbury (Penrith, Windsor, Richmond, North Richmond, St Marys, Riverstone, Pitt Town, Cattai, and Sackville), the Blue Mountains (Bathurst), and in the Mudgee Region (Burrandong), which accompanied great loss of property and life.

Following are some of the accounts given at the time, including first-hand accounts of bravery and loss.

FLOODS IN NEW SOUTH WALES.

THE HUNTER

The following is from the Maitland Mercury, 25th June:—

Hitherto it has been the custom of our residents in all discussions about floods to refer to the flood of August, 1857, as a standard — as a sort of maximum not likely to be exceeded. The rule has been good during the many visitations of the last ten years. This time, unhappily, we have to record an exception. The water in the river has in this instance reached a height certainly above that attained in August, 1857, though the amount of excess is and will be in dispute.

This flood will be remembered, not merely for its great height, but an account of the peculiarly distressing circumstances attending it. One of these was the rapidity of its rise; another, the fact that many of the residents in the Horseshoe Bend, that thickly populated part of the town, depending to some extent upon the protection of the embankment, delayed preparations for removal until too late; another, the prevalence of sickness in the town, especially amongst children; another the continuance of a bitter wind and driving rain, during the time that sick and healthy alike had to make their hurried escape from the habitations in which many of them left their all to the mercy of the rising waters.

Gloomy indeed did the prospect appear on Saturday morning. The river continued rising with great rapidity; the telegrams from up the river were most unfavourable; and, to crown our miseries, showers of the heaviest description fell at short intervals during the whole day. Added to this the wind blew in occasional squalls with all the force of a hurricane. In one of these tremendous squalls, about ten a.m., the new pile-driving machine, lately constructed for the purpose of driving the land piles of the new bridge, was blown completely over. This accident occurred just in front of Messrs. Solomon, Vindin and Co.'s sugar store, near the river bank, in which at the time several men were employed in stacking some goods in a higher place. Fortunately, the mass of timber (some fifty feet in height) fell clear of the store, but one of the men, who was just about to cross the street, had a very narrow escape.

At this time the water was breaking over the Oakhampton-road, from the pound, as far as the house at the commencement of the Falls embankment, and a culvert across the road near Burn's old mill had given way. Further along the embankment itself stood nobly, having been continually watched by the corporation labourers, under the direction of the aldermen and some more energetic residents of that locality. To their care and watchfulness may be attributed the fact that Risby's hotel, together with a number of houses in that direction, remained free from flood.

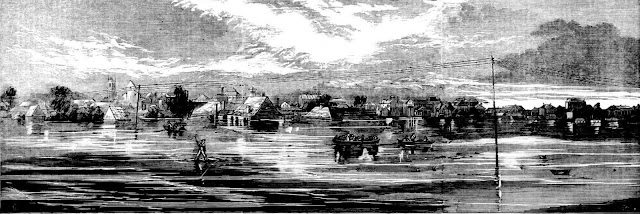

|

| West Maitland from Elgin-Street June 1867 |

Near Hall's Creek, the scene there was a very deplorable one; the dame across the creek appeared to remain firm, but the torrent was rushing across in such a manner that it could be seen that a new channel was being gradually worn away just above the dam, and the impeding fate of the house occupied by Mr Mears, which was ultimately swept away, could be plainly foretold. During the whole of Saturday the most energetic efforts were made by the municipal council to warn the people in those parts that were yet liable to inundation, as well as to remove those who had been too confident in remaining in their houses. Besides there was the necessity of providing food for the many who had already been drivers from their homes by the flood, most of whom had saved nothing but the clothes they wore.

Sad indeed it was to see these unfortunate families, many of them with sick children to whom the removal into the keen damp air must have been little better than a respite from a certain drowning to an equally sure death by the aggravation of their disease. But there were many charitable and liberal hands stretched forth in relief, and numbers of those who had escaped the flood, were unceasing in their efforts to provide for the sufferers. The boats, too, during Saturday, did excellent service, and were successfully occupied the whole of the day in removing people from Louth Park, Dagworth, Bolwarra, and other flooded localities, often bringing as many as twenty people in a load. Some of these unfortunates were taken from the roofs of their houses, after having been clinging there perhaps for hours. In several instances it was found necessary to break through the roofs in order to release the inmates, the doors and windows being all submerged.

Thus Saturday wore on, and by night the water was rushing in a torrent down Hunter street, and along Victoria-street, past the School of Arts, and it is said that at this time it was one unbroken sheet of water from there to East Maitland, along the road. From the Commercial Hotel to the Bank of New South Wales, the street was covered to a depth of more than two feet. The embankment behind

Patterson's, however, stood well, by dint of unremitting attention, and saved the houses near Mr Sawyer's. In Mr G. Smyth's the water was only a few inches deep at the worst, whereas in other floods in '63 and '64 there was a depth of four or five feet.

In the course of the evening the clouds cleared off, and the stars shining brightly gave a cheering promise of improvement, although the waters still continued to rise. Sunday morning dawned fine. Before daylight shots were heard from across the river, and being repeated from Free Church-street, a boat was immediately got in readiness. The signal of danger, however, having been first heard from the direction of Mr Doyle's farm opposite the end of the Government-road, the boat proceeded thither, and succeeded in rescuing two men who were almost exhausted from holding on to a fence. Other boats were shortly at work, and numbers of families were placed in safety in the course of the morning.

About 7 o'clock a very unexpected accident occurred. The river bank at the end of Hunter-street would appear to have given way bodily for the cottages on the river side of the street were first carried away and shortly, afterwards the neat weatherboard cottage occupied by Mr Hodson was seen to roll completely over, and was carried away by the torrent. Mr Hodson and his family had left early on Friday, but all his furniture was left in the house, and will be totally lost. The row of houses known as Ranfurly-terrace, then began to crumble away; the first went soon after Mr. Hodson's, the second broke up in the course of the afternoon, and during the night the whole terrace disappeared. A farm house was also washed away.

The river came to a stand-still on Sunday, shown by a mark at the rear of Messrs Wolfe and Garrick's stores being 6 in. above the level of 1857. No perceptible difference could be discerned until late on Sunday evening, when even those most disposed to take a gloomy view of affairs could not help admitting that the water was rather lower. It was fortunate that the weather remained fine overhead, and also that the wind, by shifting to a westerly direction, was assisting somewhat to carry the waters off to sea.

The View From The Tower Of St. John's.

The view from the top of the tower of the Catholic Church of St. John, West Maitland, would at any

time repay a person for the trouble of climbing up, and on Sunday afternoon we were kindly permitted to ascend for the purpose, of witnessing thence the extent to which the town and its vicinity was inundated. The scene was indeed a sad one; water in every direction, dotted with houses more or less submerged, some up to the windows, others up to the eaves, while many showed little beyond the chimney stack above the flood. So confusing was the effect of this expanse of water, that it was not until after a lengthened scrutiny that various localities could be clearly recognised.

Looking from the western side, the watery waste extended from the river on the right hand through Charles-street, and Mr G. Smyth's yards and workshops, across beyond the railway to the left as far as the high land known as Peach Tree-hill. In front, that part of the town along High-street from the Bank of New South Wales and the Post Office, as far as the Northumberland Hotel, appeared the driest of any, being insulated beyond, however; by the water then covering the further part of the Long Bridge. Towards the south-west, Bourke Land again, and towards St. Mary's Church, appeared

tolerably dry; while beyond Burns and Anderson's new mill the water extended in an unbroken sheet. The railway station and goods shed had the water up to the windows. The line itself was, of course, totally invisible, while some of the trucks and vans scarcely showed themselves above water. Dagworth and Farley presented the appearance of a lake, the whole being so completely covered that the course of Fishery Creek could not be discerned in the least.

Turning towards the south, the racecourse appeared to be quite under water, the trees in the centre having the appearance of growing from a little island. The old slaughter-house across the racecourse only showed its blackened roof above the flood. St. Paul's Church was surrounded, the water appeared nearly as high as the arch of the doors; the parsonage, St. Ethel's and Mr. Colyer's cottage, together with a cluster of houses near Polka Castle, were evidently more or less submerged. Boats were plying in the direction of Louth Park, there being scarcely even a fence visible looking towards Yarrabong Tannery. The buildings from J. Lee and Co.'s, Callaghan's, and the High School, as far as Cohen's Stores, presented a more solid aspect, but any break in the line of buildings showed that the streets were covered with water.

Looking thence towards East Maitland, the watery expanse again appeared; not a sign of the road was visible, and even the Victoria Bridge showed only the top-arched rails. East Maitland looked to be, except upon the hills, as badly under water as the West. Perhaps the most deplorable part of the whole picture was the Horseshoe Bend, the whole of which excepting a small portion near Dr. Parnell's, was entirely covered. The number of poor families who have been driven from their homes in this quarter must have been very great. A thin black line, curving from near Cohen's back stores, past Mr Tucker's residence, and along by Mr Proctor's cottage, showed that a part of the Horseshoe Bend embankment at least, had withstood the flood. Hunter-street and the Government-road looked like canals, and the illusion was completed by the boats rowing along them. The river in its curves and turns from the Falls to East Maitland could only be distinguished from the waters all around by the greater strength of the current, which became arched by its velocity; and as far as the eye could reach in the direction of Morpeth the water was spreading out on all sides. Phœnix-park, Narrowgut, and the flats in these vicinities, might have been taken for an inland sea. It was the same across Bolwarra; the house of Mr M'Dougall was just above the stream, but on either side and beyond, through the trees as far as one could see, the flood had covered all the land, leaving here and there a roof top or a hay stack to show that it had once been dry. The whole scene was one of desolation and misery; and without having witnessed it few would understand the extent over which it is spread.

Rough Notes at Various Points.

On Monday morning, at the north end of the town, the Northumberland-bridge was free from water, and about one-third of the long bridge was dry, on which part numbers of people were congregated to gather the driftwood, pumpkins and any other things of any value, which were arrested in their onward course by the side of the bridge. Amongst the timber were numerous snakes and other reptiles, several of which were killed by those engaged in securing it. The wooden parts, of a house or houses were also piled on the bridge. Carts were employed taking persons across the flooded part of the bridge, the drivers of which seemed to reap a good harvest, the charge for one person going across either way being a shilling. The bridge is now full of large holes, and several of the rails at the side are gone, the former caused by the great traffic across, and the latter by the action of the flood-water and drift-wood.

On Campbell's-hill numbers of persons were staying all day, and a great many had their abode taken up in the hospital, in which institution a woman, who had been removed, on Friday, from Polka Castle to that place, died. In Semphill-street, from the Northumberland yards to the Falls Hotel, the road was completely torn up from the action of the water. The sides of the culvert that had fallen in on Saturday were gradually crumbling away, until a large space was made, through which the river water rushed towards the Northumberland-bridge. The fence of one of the pound yards was completely carried away; and parts of the fence of the yards adjoining. The ground in front of the court-house was all cut up, the steps having fallen in, and the earth being carried away from round two sides of the building nearly to its foundation.

At the north end the water swept away the ground to the depth of four or five feet, which, on Sunday, had to be strengthened by a framework of wood, backed up by earth carried from the back. The falling of a fence on the opposite side relieved the pressure of water on this end, and thereby helped the slight embankment made. The south end was protected by sand bags, the water rushing furiously through between the court-house and two cottages, which are divided by a narrow lane. The chimney of the cottage next the court-house fell in, and part of the kitchen to which it belonged. The inmates and furniture thereof were removed to the court-house where they remained till Monday morning. Had the flood continued for another ten hours, the court-house and cottages might have been swept into the water hole at their rear; the court-house being rapidly undermined, and the cottage commencing to be filled.

The water at the embankment over Hall's Creek-bridge had subsided by about three feet on Monday morning, the Maitland side being dry to where the bank had fallen in, which took place on Sunday. In consequence of the strengthening of the Falls embankment, Mrs Risby's hotel escaped injury. The work done by the boats crews cannot be too highly spoken of, and we much regret we cannot record all the acts of gallant daring in saving human life that we have heard, of, as well as the names of all who were conspicuous in performing, these brave deeds.

Two boats came up from Newcastle Friday evening, one the police boat, and the other a volunteer crew consisting of Hickey (the champion puller), Jackson and Cook, who, on hearing of the flood at Maitland, nobly offered their services, and on arriving placed their boat under the charge of Mr J. E. Wolfe, who acted as coxswain, Mr H. Conseus pulling the fourth oar. On Friday night the volunteer boat proceeded along the Horseshoe Bend, and brought off several persons from this locality. On Saturday morning they took the direction of Louth-park, whence they removed a number of people, among whom were about twenty-five individuals of various families, who had taken refuge at the Yarrabong tannery. Near this place they also rescued a person named Mrs Smith, by taking her through the roof of the house. On Sunday morning this crew went in the direction of Bolwarra, where, near Mr Doyle's farm, a number of people had taken refuge in a shed on Friday night.

By Saturday night the river, had risen so high in the shed as to render the position of these people very precarious. There were seventeen in number of them altogether, including two infants in arms. Several boats attempted to relieve, them on Saturday, but, owing to the fearful current, were unable to approach. Early on Sunday morning, the shed showed signs of giving way, and these unfortunates were compelled, as a last resource, to cling on to a fence outside. This refuge would soon have failed them, when the volunteer boat drew near, and, in spite of the danger of the attempt, contrived to get a line to the unfortunate people. It was then a work both of danger, and difficulty to get the people on board, and Hickey and Jackson had narrow escapes for their lives, but happily they succeeded at last, and conveyed the whole of them safely on shore.

Another gallant feat was performed by this crew on Sunday night. It appears that, on Sunday evening, a boat was going along the river, in which were four persons — Messrs. C. Bowden, J. Vickery and another, besides, a young man named Thomas Clark. It happened that the boat nearly ran against a tree, and Clark, in trying to fend her off, lost his balance and fell into the water. Being a good swimmer, he made for the boat, but according to his own statement, his companions pulled straight on, and made no attempt to rescue him. Clark then swam to a tree which happened to be near, and made good a lodgment among the branches. There he was seen by Messrs J. Fulford, jun., and Medlam,who at once rode off into town to give the information.

On hearing the news, the volunteer crew instantly set off to the spot, nearly opposite Bolwarra House, but on arriving there they found it would be too risky to attempt reaching the poor fellow in the darkness which had then set in. They, managed, however, by signals, to let him know that help was near, and that they would not desert him; the people on the river banks also made up large fires, with the same object. As soon as the first beams of day appeared on Monday morning, the, boat again drew near, and, fastening a rope above the spot, the gallant crew were able to swing round to the tree and rescue the man, who, as it may be supposed, was by that time tolerably exhausted.

FROM BATHURST TO PENRITH.

Here is another gloomy picture by a special reporter of the Herald:—

At Bathurst and in its vicinity the floods have done considerable damage. Never was there such a flood known in the district. Before the fall of the bridge the water had surrounded and filled many dwellings on the low grounds, forcing the occupants to flee for their lives. The greatest amount of mischief was done on the flats below the town, which were all overwhelmed. One brick-maker lost several kilns of bricks, in addition to all his household goods. Goods of every description were to be seen floating down superjecto æquore.

On Thursday night most of the people had been forced to quit the flat and seek higher ground. During the night the approaches to the Vale Bridge were swept away, and the flood was then rising at the rate of six feet per hour. It continued to rise until the afternoon of Friday. The main bridge was carried away about noon, when the water had almost reached its greatest height. There were large numbers of people upon the bridge at the moment that it began to yield to the might pressure of the water. Most of these imprudent people made their escape to the Kelso side, and were obliged to stay there. Mr Rutherford (of Cobb and Co.) built a punt for conveying the mails across the river. In that they were enabled to return into Bathurst.

The destruction of property around Bathurst has been very great, but as yet it would be impossible to state its extent. One life was lost. A shepherd in the employ of Mr Walter Rotten was drowned below Kelso, while endeavouring to save some of his master's sheep, 800 of which were destroyed. The Fish River overflowed a large extent of country, but did little damage. Hartley, also, being built on high ground, escaped almost scatheless. The skillion of one place — Stewart's public house — was carried away entirely. All the hotels between Hartley and Bathurst were filled with weather-bound travellers. In some cases, people who were separated from their homes by a gully or ravine were unable to get back, and were forced to wait until the flood subsided.

Penrith, as seen from Lapstone-hill presents a singular appearance. The flood has subsided, leaving behind it vast accumulations of debris, heaps of mud, and pools of water in every direction. The flats and low lands wear a sombre tinge, as if the verdant fields had put on a mourning dress. The desolated huts cropping up hero and there in the dreary waste are inconceivably dismal looking. I have never seen so miserable a spectacle. The grief that is lying at so many hearts seems to have saddened even the face of Nature. The very animals, what few there are, seem to be infected by it, and have a woebegone dissipated aspect. The river — broad, muddy, swift — glides on as if it had never been the instrument of desolating homes or blighting the hopes of mortals.

The losses caused by this flood are fearful. It is impossible to estimate them. Hundreds are rendered penniless and homeless. Many, from being, well-to-do, are reduced to abject destitution. It is pitiable to witness so much misery. I hear that upwards of a thousand valuable horses have been drowned in the neighbourhood of Windsor alone. Penrith has not suffered so-much, but its woes are bad enough. I will not now relate the tales of wretchedness that have been told to me to-day. They are such as one seldom reads of— such as one could not relate with calmness.

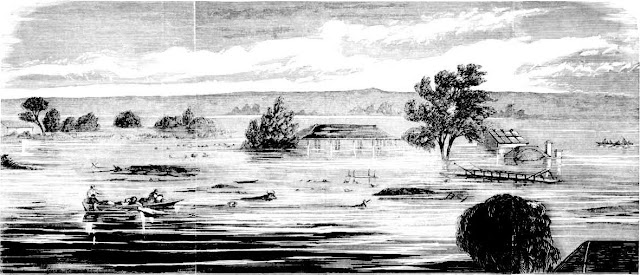

|

| Ryan's Punt, Near Windsor June 1867 |

Large, quantities of land on the banks of the Nepean have been swept away. Farms have by this means been entirely destroyed and their owners left landless as well as penniless. A settler, named Gow, living about three miles above Penrith, lost the whole of a five-acre paddock at one sweep. A person named Stone has also suffered a similar but more extensive loss, about fourteen acres of his land being swept away. It was some of the richest land on the river. There had been a great deal of stock drowned, and below Penrith haystacks and other things may be seen lying on the banks of the river. Houses have been swept bodily away, and others have been torn to pieces. The "hairbreadth 'scapes" are numerous.

One woman was going to put her children to bed when the wall of the hut fell right across the bed in such a way as would inevitably have killed anyone lying in it. She fled from the place, and though she had to wade with her children for a long distance, she at length reached a safe spot.

A Mrs Euston was lying ill in her bed in a very feeble state, when the flood came down and half-filled her dwelling. She had to wade up to her waist in water, with an infant in her arms, for nearly a mile to save her life. She reached dry land and was well cared for, but her life is despaired of.

A settler named Morgan, his wife and two children were flooded out of their home, and took refuge on a hay-stack. The waters rose around them, and the stack was just beginning to float away when a boat came and rescued them from certain death. Scores of such stories are told.

The road to Castlereagh is utterly impassable, and the flood has been very high there. The water stood two feet six inches in tho Wesleyan chapel, which is on high ground. Great numbers of cattle, horses, pigs and other animals have been swept away. The punt approaches on both sides of the river at Penrith have been utterly destroyed.

Many of the unfortunate people who have been flooded out, are wandering about in a miserable objectless way, trying to pick up such remnants of their household goods as they can. Some of the houses are full of mud which is level with the windows, and the former occupants are trying to make them once more habitable."

AN INCIDENT OF THE FLOOD - BURRADONG.

Mr F. B. Sutton, writing from Burrandong, describes one of the saddest incidents of the flood :—

The hut of a shepherd of Mr Blunden, named Baker, who lived near the junction of the Mudgee River, got surrounded before he and his family could move (the water rising six feet in ten minutes), and out of eleven persons all were drowned but three. Those saved are the eldest boy and girl and father. Those drowned are the mother, five boys, a baby (girl), and a married man named Smith, who came to help them about dark, just before the sudden rise of water.

At the first rush of the flood, they all got on to the tables, then on to a loft, and then had to cut a hole in the back and get on to the top of the roof. Here they remained until the water reached their mouths, when the four left alive swam to a tree. Smith not being able to swim sank as soon as he left the hut.

The poor old father (Baker) gave a most distressing account of the scene — how he held his children in his Arms, dropping them as they died (of the cold he says) to take up others that were alive, until none were left. He says the dogs, cats and fowls kept swimming round them and jumping on them all the time they were on the hut. The survivors were rescued about day light by the brave wife of the man Smith, who pulled a boat about a mile to the hut, and then took them to the shore. She heard them cooeying for a long time, and started to try and save them, which she had great trouble to effect, the current was so strong."

The following particulars were elicited during a magisterial inquiry into the matter :—

Isaac Daniel Baker recognised the bodies as those of his wife Mary Ann, aged about 48? years; of his seven children, varying in age from 8 months to 13 years; and of Frederick Smith. He deposed: I am a shepherd in the employ of Messrs Blunden, and live near the junction of the Mudgee and Macquarie Rivers. On the 21st, when the sheep came home, about 5 o'clock p.m., I went to the bank of the Macquarie, to see how the river was. I saw it was rising. There was some high ground at the back of the sheep-yard, where I had made a gateway to let the sheep out in case of a flood, this was between my hut and the river. We put in the sheep, and I went in to supper with all my family. I told my eldest son Moses we would have to remain up all night and watch the flood. After we had supper my two children, who are now alive, went to see the flood, and returned and told me that the water was coming very fast down the gully, and was within two or three hundred yards from the hut. When I went out, the deceased, Frederick Smith, was coming towards the hut to render me assistance, he said the water had risen six feet in the Mudgee River while he was at supper, and asked me what I was going to do. I said we shall get the children out.

We went to the hut, and I told my wife to get the children ready, as the water was coming round us fast, but there was still dry ground. In about ten minutes from that time when I went out again, I found that the water had entirely surrounded us, and there was no possibility of escape. We then all went into the hut, I fastened the door, and about twenty minutes afterwards the water began to come in. I then put my wife and children on the loft over the bedroom, and stood on the table. I was not afraid, as I had hopes that the water would not rise much higher. At this time Frederick Smith was sitting on one of the beams of the loft. When the water reached the table I got off and sat on another beam. In about three-quarters of an hour the water rose to the top of the wall-plate, I then got a tomahawk and cut a hole in the bark of the roof. The deceased Frederick Smith got out first. I handed the children out to him, and the rest followed.

When I got out the moon had just risen, and there was no land to be seen. I then cooeyed for the first time, it being then about 9 p.m. We were all cooeying and in about three-quarters of an hour heard a voice in the distance and thought it was from Mrs Smith, wife of the deceased F. Smith; they lived on the Mudgee River, about a third of a mile from my hut; the water at this time was about ten feet above the floor of the hut; a short time after this, I heard Mrs Smith call out, and and ask me if Fred

(her husband) was all right; I called loudly for help, and told her to go to Mr Blunden's for the boat; we thought she understood us, and her husband told us not to shout any more, as it might bother her; some time after, as the water still rose fast, I cooeyed again, and she answered; I then felt sure she had not gone to Blunden's; when the water reached the ridge-pole on which we were sitting, seeing no possibility of escape, I told the children to pray; we all joined in prayer; we were all composed but one little boy who was crying; the water continued to rise, and we had to stand on the ridge-pole; about half-past three in the morning the first of the children died — Frederick, seven years old — the water being then up to my middle; he was not drowned, but died of cold; just after this my boy Daniel, aged 13 years, said, "God Almighty bless you all — I cannot stand it any longer;" I held him

till he was dead.

The next to die were John Isaac, aged 5, and Thomas Edwin, aged three years. They were in the arms of my son Moses, who said, "Father, these two children are dead — what shall I do now ?" I said, "Go to the tree while you have strength so that some one may live to tell the tale." He said, "Father, I believe I shall be the only one saved." He then kissed me, and swam safely to the tree, which was about twenty yards from the hut. I called to him that his mother was still alive, and that I would hold her as long as there was life in her. Some time after this, my wife died, and I let her go. I then went to take the baby from my daughter Cecilia; but she said, "No, father, you cannot hold her better than me, and I cannot hold her much longer." I then kissed her, telling her to hold the baby as long as she could, and then to swim to where her brother was. I swam to the tree, and with the assistance of my son Moses, got on the limbs.

A very short time after I heard a splash, and Cecilia calling for help. I heartened her to strike out, and she came within arm's length of us. My son Moses leaned over, caught her, and pulled her up the tree. The water was up to her chin when she was washed off the hut, and she dropped the baby. Andrew William, aged nine years, died just before I left the hut. About that time, also, the deceased , F. Smith, who was holding Henry Shadrach, aged eleven years, told me the boy was dead. I said, "You have done all you can, you must try to shift for yourself — can you swim?" he said, "No, give me what directions you can — I may have a chance." I did so, and he started for the tree, but sank at a short distance. About sunrise, Mrs Smith, wife of the deceased F. Smith, came by in a boat by herself, and released my son Moses, (17 years), my daughter Cecilia (15), and myself — the only survivors of our family — and brought us to dry land. Mary Anne Smith deposed to the difficulties she met bringing the station boat to the rescue, without assistance, as soon as day light permitted, and the exhausted state of the unfortunate survivors. The bodies of Mrs Baker and her seven children were all found near the hut when the water subsided, and presented a heartrending spectacle.

AT THE earnest request of some respected friends, I have written this account of some of the sufferings and dangers to which myself and family were exposed during, the calamitous flood of June, 1867:—

I was residing in the Lowlands of Richmond at that time, where I have lived in comfort for the last thirty-four years: my home is now a complete ruin, so is my daughter's also.

On Tuesday the rain commenced, and continued on Wednesday. The river began to rise on Thursday morning, the water beginning to cover the lower end of our farm. We then sent our horses and cows to Richmond (Ham Common), with the exception of one blind horse, belonging to my son-in-law, Mr. Duncomb. With him (the horse) he brought his wife and family, furniture, and in fact, all that was movable to my house. He then went for my William's wife and two children, who at that time lived on a portion of Mr. Single's Farm. He also brought away his furniture, and everything that could be secured, such as harness, machinery and farm implements, together with as much corn and other things as could be carried up into the grainery — the water still rising fast. Next thing we did was to make a plan for getting the pigs up on top of some hay in the large barn. Having lost all our pigs in the Flood of 1864, we did our best to secure them. About seven o'clock the same evening, my daughter Emma went, over to William Bailey's, who is my nephew, and brought away his wife, and four little girls to my house, through all the pouring rain and wind, the mother carrying her youngest, about nine months old, and my daughter (Emma the next youngest:, the other two little ones -had to walk, falling down every few rods — it was so very dark and rainy. It was well they did come or probably they would have shared the same fate as the unfortunate Eathers. Their Father came over also to bring a change of clothing for them: but went to his house again. As for the children, they were soon undressed and washed, and put into a warm bed, in which they remained but a short time, as the room they occupied was on the first floor of the house. About the same time that night, my son William took a lantern over and wanted the Eathers to come to us, but they did not come . Thomas Eather said they would come when the moon arose, if there was need. I am sincerely sorry they did not come, as they were all over at my house in the Flood of 1864. They doubtless would have been saved with us, as it was the Lord's will to spare us all. But it is a subject too painful for me to dwell on, so I will say no more about them.

We then commenced to carry all our furniture upstairs. I. forgot to mention that after having made a secure place for the pigs, it took upwards of three hours to put them up by means of a pair of blocks and a rope. It was a very difficult job, some of the pigs being very large, and numbering about sixty: the rain coming down in torrents the whole time. About twelve o'clock on Thursday night, the water came into the house; but did not rise very fast at that time, the water being only about three feet high in the house on Friday morning; but it rose very fast all day on Friday. About four o'clock on Friday afternoon, it wanted about four feet to put it on the second floor. We did not do much that day, except watching for and expecting and expecting to see a boat every moment. We put some of our clothing up in the roof in the evening, little thinking that ere a few short hours, we should have to seek refuge there ourselves. We baked some bread, but had no heart to eat, but the little children could— and it would not do to be without for them.

Finding the water still rising, we all knelt down and offered a prayer, if it was His will to save and deliver us. We then made a stage by lying two cedar tables beside a bedstead, pulling beds and mattresses on it. We first got up. First there was Mrs. Duncomb (who I shall call my daughter Mary,) and her five children; my son William's; wife and two children; William Bailey's wife and four children; my daughters Emma, Matilda, Elizabeth, Charlotte, and myself. We had not been above an hour there be fore the water was about a foot high on the floor: we then thought of going up into the roof, but had nothing to break a hole in the ceiling with except a pair of tongs — with which, we contrived to make a hole large enough at last. We then had some beds and mattresses put up to sit on, and were then helped up. By the time we were all up, it, was about eight o'clock. At this time the wind dashed the waves up against the house fearfully, the water rising very fast. We were all anxiously watching it through the broken ceiling.

Between ten and eleven o'clock the whole end of the house fell out, and the roof began to give way. That was an awful moment. It struck terror to our hearts. We thought every moment would be our last: crushed to death beneath, that fearful roof. To hear the screams of parents, and their dear children clinging to them crying, will never be forgotten except by the younger children. Yet at that time the Lord gave me great fortitude.. I stood up and tried to get them to listen to me, but the cries of my daughters, of father, mother, brothers and sisters, and all the dear children, seemingly all to go: "We have tempted Providence: we shall all be lost," I said, "Let us pray to the Lord, for we do not know one moment from another, when we may be called into His presence." But it was no use at that time.

I knelt down and prayed to the Lord to save us all from the awfully sudden death that threatened us. I said, "I will put my trust in the Lord: He will not forsake us." I could not think that we should be lost; it seemed as though something told me that we should not. At at once Mr Duncomb said, "I will make one to go and try if we can get into the granary," a new wooden building which stands some distance from the house. So he and my son William slipped and went down into the water, and then my husband: they said it was not safe to stay in the house any longer and they would try to take us to the grainery. They wanted me to go first. I said "No let the mothers and children go first." My daughter Mary, another baby about seven months old, went down first: then my son called to his wife to come, but she did not want to go: it was only thirteen days since her confinement: but she did ultimately go, with her young babe and her little girl Edith — about two years and eight months old: and then came Mrs. Bailey with her baby. The screams and cries of the poor dear children when they first got into the water, were most piteous to hear. The first thing that came to hand was a three-cornered cupboard that was floating past. Mary and little Horace were the first to start from the house to the grainery. They were almost swept away by the current. Her brother sprang and caught hold at the end of it: and saved her from drowning, not before her head and shoulders, and the baby she had with her, went under the water. William's wife and their little girl went next: and then Mrs. Bailey with my son's baby and her own, both in her arms. They landed without any further accident. My daughter Mary said, "Bring my other four children over," but they found it was useless, they being up to their waists. Mr. Duncomb and my son William, were so cramped and perished by the cold water that it was with the greatest difficulty they could be got up into the roof. We were a long time rubbing them, to bring warmth into them again. My daughter, Emma was down in the water, waiting for the mothers and children to come back again into the house. Mary said, "I will not venture back again,. I will stay where I am. I shall lose my baby if I go back." The poor dear child was almost dead then with the wet and cold. But his Grandfather said "I will take your baby back safe." He took him in one arm, and swam across with the other, gave him to his Aunt Emma, she gave him up into the roof to her sister Elizabeth, who stripped him quickly, and. gave him to his father — who was a little better by this time. His mother came next, and William's wife, and her baby, which was given. Up into the roof and undressed. The poor, dear baby was almost dead with the cold. I took off my flannel petticoat, and wrapped him in it and a large shawl. When he was a little warm he began to cry out piteously. I did not know what to do with him, so I put him to my breast and that soothed him to sleep.

After bringing over the two mothers and three children, the last of which was William's little girl, her Grandfather sat her on the mattress and brought her over by herself. By this time my Husband was quite exhausted and could not go back for Mrs. Bailey and her child. All at once I heard my daughters cry out "Save ,Father, save Father, he will be drowned." They held out a piece of a bedstead-top and begged him to try and hold on to it, while they drew him in with a great deal of trouble. And now another difficulty presented itself to us how to get him into the roof again. But with the assistance of his three daughters and William's wife, we got him up at last. He is a very heavy man.

And now a new trial awaited: as Mrs. Bailey and her baby were left in the grainery, and she kept saying, "My baby will be drowned." My husband said, "Tell her not to be frightened: I will go for her as soon as I get better." Which he did. All were then back in the house again.

My daughters, Mary and Emma, said "Let us stay down now, till we put all the furniture out: and everything we can out of the house." Which they did. My daughters, Mary, Emma, Matilda and John's wife were in the water for more than two hours. They were almost perished, and bruised all over with the water washing the furniture up against them. Had they not persevered, the walls must have been broken down be fore the morning. We were all settled down once more, to wait the Lord's will. John thought of the windows under the end of the house where we were sitting not being open. We then set to work to break the ceiling over each window. Then my daughters reached down and with a gun broke the glass, which seemed to ease the surging of the water— it having free course through the house. This being done, we could do no more. All the excitement over, we sat down once more to wait the Lord's pleasure, watching most anxiously for daylight. When having nothing else but a gun, my son William, with the assistance of my son in-law, knocked the shingles and battens off the end of the roof, put up a white flag, and commenced calling as loud as they could. About seven o'clock on Saturday morning, they saw a boat coming straight for the house. It is impossible to describe our feelings. We could scarcely believe it. Mr. G. Cupitt, jnr., seeing the flag got a boat, and with the assistance of Mr. Wester, the school-master at Freeman's Reach — came to rescue us from our most perilous situation.

I had forgotten to mention that there were two old men in the grainery in great danger but they were saved too. There were sixty-two persons saved in the same, grainery in the year 1864 but the water was sixteen feet higher in our house, this time.

I really do think it was a mercy the Lord stirred us up to such a state of excitement. For if we had to have sat still, all that long night, I fear some of us would have sank-under it. But blessed be His Holy Name, He stood by us all that fearful night and sent us deliverance at last. I forgot to mention that my son commenced firing on Friday afternoon; and continued to do so at intervals. Just before we got up on the roof he fired his last charge of powder, but all in vain — no assistance came to us. In the midst of all the terror and excitement, and during the time they were going, over to the grainery one of my little Grandsons begged most piteously to bring his Mamma back to them again. "Do bring my ma back; don't let her stay there." He then caught his Aunt Emma by the hand and said, "Pray, Aunt Emmie, pray." He then commenced, the Lord's Prayer, "Our Father which art in Heaven . . ." in a voice so calm, it seemed as if the voice came from Heaven — so calm and solemn to the end of the prayer — in the midst of terror, confusion and danger of every kind.

I have written this as near as I could, but cannot tell half.

Signed — .

E. SMITH

Sources:

- Floods in New South Wales (1867, July 20). Illustrated Australian News for Home Readers (Melbourne, Vic. : 1867 - 1875), p. 12.

- From Bathurst to Penrith (1867, July 20). Illustrated Australian News for Home Readers (Melbourne, Vic. : 1867 - 1875), p. 14.

- An Incident of the Flood (1867, July 20). Illustrated Australian News for Home Readers (Melbourne, Vic. : 1867 - 1875), p. 14.

- Graphic Story (1927, November 11). Windsor and Richmond Gazette (NSW : 1888 - 1954), p. 1.

No comments