|

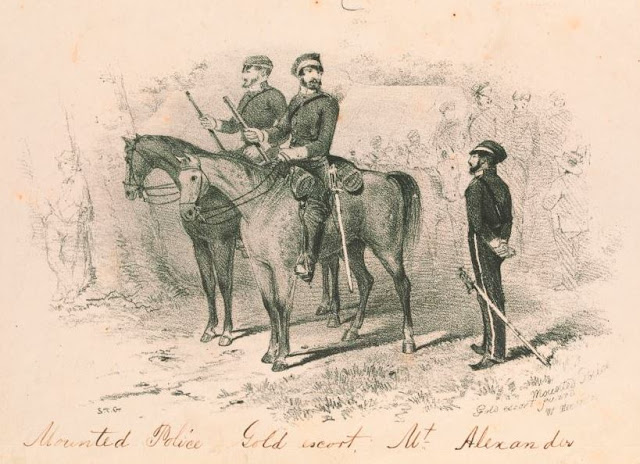

| Victoria Mounted Police 1852 |

OLD TIME MEMORIES

POLICE IN THE FIFTIES.

THE CADETS.

By ONE OF THEM.

Of the many troubles that beset the Government of Victoria at the time of the discovery of gold none was more acute, probably, than the insufficiency of the police. Horse-stealing was of such common occurrence that it came to be regarded as a necessary evil. No traveller, whether he were horseman, or carrier, or paterfamilias, driving his family through the country, could feel sure of finding his cattle again once they were allowed out of his sight. It was the practice, where several persons travelled together, for one to be on guard all night over the horses. But horse-stealing was a mere trifle compared with the scarcely less frequent atrocities by bushrangers and highway robbers. The streets and suburbs of Melbourne and Geelong were no more secure from crimes of violence than were the bush roads or the gold-fields.

It was not until the end of '52 that the first serious effort was made to establish a properly organised police force. Even then it was a very difficult matter to find recruits of the class which form the main body of the police in the old country, but, luckily, there were a good many young men about who, from early training and education, were not quite fitted for the rough and laborious work of the diggings. It happened that amongst the many persons attracted here by the gold discoveries were retired army officers. Several such others were deputed by the Government to raise a corps of cadets, who, after due training and probation, were to be the superior officers of the future police force.

Captain James Fox, late adjutant of the 75th Regiment, was authorised to enrol a detachment. He entered on his work in November, 1852, and a few days later I accompanied a friend, who had met Fox with his regiment, to the Richmond Police Camp. We had but just landed from the SS Great Britain, after a long but not unpleasant voyage. At Cape Town, where we called, my friend had laid in a small cask of Cape sherry, most fiery of wines, and, knowing Captain Fox's tastes, we brought this stuff with us to his camp, slung on a walking-stick with our handkerchiefs. Fox was a robust, dark-visaged man of somewhat stern appearance, but a few pannicans of sherry set him talking about work, and after dilating on the fine set of young fellows he had already secured, and the prospects before them, he wound up by asking me to make one of his detachment.

As the dinner hour approached those cadets that had already been enrolled turned up, and I was introduced to them them in due form. Amongst them were two English barristers, a civil engineer, a bank manager from Belfast — the oldest man of the lot — a medical student — the son of a wealthy Leeds manufacturer — and the rest, like myself, of no particular calling. They seemed to be a nice set of fellows, as Fox was careful to point out. I held out for a few days, but yielded at last to Fox's blandishments.

Our number was soon completed, and steady and regular drill commenced. Our hours of drill were from 5 to 7 a.m., and from 4 to 6 p.m., besides sentry-go and other duties. Drill under a man like Fox was by no means holiday work. The mounted cadets had to clean their horses, arms, saddlery, &c. Fox was our sole instructor, and, although exceedingly strict on the parade-ground, at all other times he treated us with much courtesy and consideration. When off duty we were free to go where we pleased, and so long as we were sober when required for actual work, and our dress and accouterments as they should be, he did not care what our condition was at other times. He allowed himself large liberty in the same respect when his day's work was done, and one of the sell-imposed duties of the cadet who happened to be on guard when the commandant returned to his tent at night was to see that his necktie was loosened and that his head was not hanging over the side of his bed. Fox must have had an iron constitution. He was always first to turn out in the morning, and alter plunging his head into a bucket of cold water (some of us thought we could hear the water fizz at times) he appeared as fresh as if he had been supping on water-gruel the night before. Several of the cadets tried to follow his example, but they were a long way behind him in carrying capacity. I was not in the running at all, for if I exceeded ever so little I dared not taste liquor for perhaps a week after, while my companions were always ready for a hair of the dog that bit them! I was temperate, therefore, from necessity as well as from inclination. From this, and from a certain proficiency in drill, my first advancement followed.

It so happened that one morning the commandant, who had had too much liquor the night before, or liquor of a bad sort, found himself unable to carry on the drill with his usual vigour. He called on the older men of the detachment, one by one, to fall out and conduct the exercises, but they very soon had matters in a knot, to the keen disappointment of their commandant. The detachment had so improved under his teaching that there was the less reason to expect such a breakdown. I remember well the confusion of the unfortunate fellows as they heard the scornful remarks of the commandant, in which were mixed many a swear word. He was so displeased he threatened to have the corps disbanded. The failure on the part of some was due no doubt to the novelty of the situation, and on the part of the rest to the fact that, like the commandant himself, they had not quite got over their excesses the night before.

As a last resource Fox called on me to put the detachment through their movements. I was then but a youth of nine teen, and did not expect to have such greatness thrust on me; but having been taught drill when a lad by the regimental colour-sergeant, quartered near my home, and having gone to bed quite sober the preceding night, I found no difficulty in carrying out all the exercises we had been trained in. The spirits of the commandant rose as he saw the cadets forming fours, wheeling, marching at the double, halting, forming on their proper front, &c., with the precision of well-trained soldiers. He shook me by the hand, and made me a complimentary speech, winding up by nominating me, in the presence of the whole detachment, as second in command. My fellow-cadets behaved like real good fellows. They did not show the least ill-feeling, but were rather pleased that one of their number had come through the trial so well.

Our accommodation in camp was pretty rough. We were packed eight in a tent, and lay on straw mattresses placed on the bare surface. At the time of which I write the grounds on which are now the beautiful Fitzroy and Treasury gardens were then a bleak waste, the scene of many a robbery, even in broad daylight. Several persons were shot and wounded there, and one man killed.

On my first evening in camp a friend and I had gone to the Muster Arms in Flinders lane — the house is still carried on under the same sign — for some beer as a treat for the fellows in our tent. It was late, and, being new chums, we did not take into account how short the twilight is here. It was pitch dark as we started on our return to camp. The lightning flashed out occasionally, and then we could see that we were followed closely by three men. We had no weapons except the bottles, with which we meant to defend ourselves if necessary. To make matters worse, my friend and I both tumbled into the gully that still intersects the Fitzroy-gardens, breaking or dropping all the bottles. We had scarcely scrambled out when we heard the men that were in pursuit of us crash into the same spot. This gave us a good start, and shortly after seeing the glare of our camp fire we made for it with all speed, where we joined our companions. We had hardly begun to narrate our adventure when we all heard cries of "Murder!" "Help, help!" a short distance off. There was a general rush of the cadets to the spot, but owing to the darkness two of the men — the same that had been following us, no doubt — escaped, while the third was caught kneeling on his victim and rifling his pockets.

About the same time a young cadet named Stapylton had a similar experience. He had been supplied with a sword from the armoury, which was then attached to the old police court buildings in Swanston-street. He did not quite know how to wear the sword, so he carried it in his hand He had loitered in town until dark, and when he was turning Dr. Howitt's corner in Spring-street, on his way to the police camp, a man sprang forward and ordered him to stand. Stapylton was so surprised that he dropped his sword and prepared for a run, but, to his infinite delight, the thief, alarmed at the clatter of the falling sword, turned and fled. The young fellow picked up his weapon, glad to have got so well out of the difficulty.

About the same time a young cadet named Stapylton had a similar experience. He had been supplied with a sword from the armoury, which was then attached to the old police court buildings in Swanston-street. He did not quite know how to wear the sword, so he carried it in his hand He had loitered in town until dark, and when he was turning Dr. Howitt's corner in Spring-street, on his way to the police camp, a man sprang forward and ordered him to stand. Stapylton was so surprised that he dropped his sword and prepared for a run, but, to his infinite delight, the thief, alarmed at the clatter of the falling sword, turned and fled. The young fellow picked up his weapon, glad to have got so well out of the difficulty.

Drill completed, our detachment received orders to march for Ballarat on New Year's Day 1853. We reached Keilor Plains on the second day, where we met large numbers of disappointed dippers returning from Ballarat. They all told the same story the place was a failure, and would shortly be deserted. Our civil engineer made up his mind to go with us no farther, stripping off his uniform, laying down his arms, and departing. We saw him no more. We expected the commandant to interfere, but the cadets not having been sworn in he had no legal right to prevent any of us from leaving. One of the returning diggers, a Dublin attorney named Macnamara, was looking on, and he offered to take the place of our departed friend. Fitting on the discarded uniform, he went with us to Ballarat. Mac's further history" was short. Not having been drilled, he was appointed watchhouse-keeper at Ballarat. The perquisites attached to the office were considerable. No records were then kept of bail money, nor of the property taken from prisoners, and anything not claimed prisoners seldom took the trouble to hunt up Mac after discharge — was regarded as the rightful property of the watchhouse-keeper. Mac held this position for a year or so, when some new regulations coming into force, he got homesick, and retired on his savings — several hundreds of pounds, I believe. He sailed for home in the Madagascar, but nothing has ever been heard since of the ship, or of Mac, or of any of his fellow voyagers.

We did not find Ballarat, in the depressed condition we were led to expect, for there happened to be some rich finds just about the time we reached there. Following these there were rich discoveries at Winter's Flat, Canadian Gully, the Gravel Pits, Red Hill, &c. There was certainly plenty of work cut out for the cadets, for reports were continually coming in of highway robberies, robberies from stores and tents. Horses were stolen every night almost, and altogether the place was in a very bad state. One of my fellow passengers, a young fellow named Maunsell, was an early victim. I was stationed at Canadian Gully, when a man who had been searching for his horse reported that he found a man lying in a dry water-course, still alive, but evidently badly wounded, and covered with blood. On reaching the spot we found the poor fellow rolling about in the dust. At first sight he seemed to be a coloured man, the blood and dust having formed a thick coating on his face. On examining him we found his skull fractured almost into a pulp. He had a bullet wound and various stabs in the chest; but, in reply to my question, he gave his name as Maunsell, but he was so disfigured that, although he and I had been eighty-four days together on board the Great Britain, I failed to recognise him. He was taken to Ballarat, where the Government surgeon, Dr. Hise, and Superintendent Foster, who was half a surgeon and a most humane fellow, showed him all possible care. Maunsell lived for one or two days. It was only when the blood was washed from his face that I recognised him. He-appeared quite unconscious, but when the attendant attempted to pull off his trousers Maunsell held firmly to them with both hands, and would not allow them to be removed. He was buried in the clothing in which he was found.

|

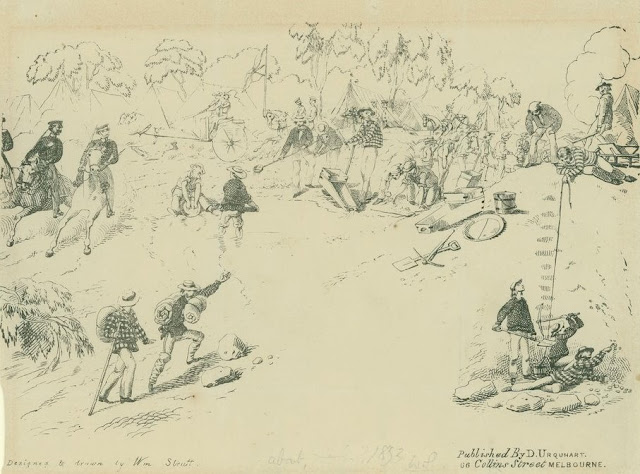

| Mount Police Gold Escort 1852 |

We did not find Ballarat, in the depressed condition we were led to expect, for there happened to be some rich finds just about the time we reached there. Following these there were rich discoveries at Winter's Flat, Canadian Gully, the Gravel Pits, Red Hill, &c. There was certainly plenty of work cut out for the cadets, for reports were continually coming in of highway robberies, robberies from stores and tents. Horses were stolen every night almost, and altogether the place was in a very bad state. One of my fellow passengers, a young fellow named Maunsell, was an early victim. I was stationed at Canadian Gully, when a man who had been searching for his horse reported that he found a man lying in a dry water-course, still alive, but evidently badly wounded, and covered with blood. On reaching the spot we found the poor fellow rolling about in the dust. At first sight he seemed to be a coloured man, the blood and dust having formed a thick coating on his face. On examining him we found his skull fractured almost into a pulp. He had a bullet wound and various stabs in the chest; but, in reply to my question, he gave his name as Maunsell, but he was so disfigured that, although he and I had been eighty-four days together on board the Great Britain, I failed to recognise him. He was taken to Ballarat, where the Government surgeon, Dr. Hise, and Superintendent Foster, who was half a surgeon and a most humane fellow, showed him all possible care. Maunsell lived for one or two days. It was only when the blood was washed from his face that I recognised him. He-appeared quite unconscious, but when the attendant attempted to pull off his trousers Maunsell held firmly to them with both hands, and would not allow them to be removed. He was buried in the clothing in which he was found.

About a week after an officer of the same name, quartered with his regiment at Geelong, wrote to Superintendent Foster, mentioning that his cousin had lately left Ballarat with a companion to buy gold, and that before leaving he had sewn up a large sum of money in bank notes in the lining of his trousers. On the body being disinterred, sure enough, there was the money as described. This furnished an explanation why the unfortunate fellow, although apparently unconscious of all that was going on, would not allow his clothing to be removed.

The cadets kept up regular patrols day and night, and very soon brought about on improved state of things. They nearly all took very kindly to their work, and some showed considerable aptitude for police duty, although one or two officers holding high positions were notoriously taking tips from sly grog-sellers, and endeavoured to draw some of the cadets into similar practices. I never heard a whisper of dishonourable conduct on the part of the cadets themselves. It was quite different with the ordinary run of police enrolled at that time; the cadets objected therefore to undertake any duty with them. I was induced to take charge of a small body of plain-clothes police, but, although they were supposed to be picked men, I found their conduct so bad that after a short trial I refused to have anything further to do with them. Naturally the cadets were in great request for all positions of trust, and the good horsemen among them were always the first chosen for the pursuit of the bush rangers, horse-stealers, &c.

Of my own company, the only survivors, so far as I know, are G. G. Morton, of Labona, near Ballarat, and myself. Of the other companies there are living, H. M. Chomley, the present chief commissioner of police; C. H. Nicolson, now one of the police magistrates of the city; Reginald Green, and George Walstab.

Sources:

- Old Time Memories (1897, August 28). The Australasian (Melbourne, Vic. : 1864 - 1946), p. 25.

- Victoria Mounted Police 1852; by S. T. Gill (1818-1880) Lithograph by Macartney & Galbraith; Courtesy: State Library Victoria (Australia)

- Mounted Police Gold Escort 1852; by William Strutt (1825-1915); Courtesy: State Library Victoria (Australia)

No comments