Adelaide Almanack Town and Country Directory 1864

The subjoined paragraphs of Mr. Edward Wilson's graphic sketch of a portion of the settled districts of South Australia originally appeared in the Melbourne Argus, of which Mr. Wilson was then editor, having been written whilst that gentleman was on a visit to Adelaide. Coming from the pen of an unprejudiced writer, intimately acquainted with Australian subjects, it most faithfully portrays the characteristics of this Colony as "the home of industrious yeomen":—

In visiting the Colony of South Australia I had made up my mind to expect a combination of intelligent industry and sound practical development, with a little of that insignificance almost inseparable from a limited community. For years past I have been thrown into constant contact with very intelligent gentlemen from South Australia who had struck me as being singularly enthusiastic in their appreciation of the manifold virtues of that Colony. I like enthusiasm, but I also distrust it. A sort of unbelief comes across me when I find assurances obtruded upon me that the Garden of Eden was situated on the banks of the Torrens; that the tree of knowledge grew at the corner of Hindley Street; and that the original cause of coolness between Cain and Abel was a difference of opinion on the eighty-acre system.

But even the casual inspection of a very small portion of the surface of South Australia soon convinces me that there really was much connected with that Colony to enlist the sympathies and justify the encomium of every real well-wisher of Australia. I have already mentioned, that at the very first step across the boundary we were met by a remarkable development of patient and painstaking industry. The same spirit is perceptible over the whole Colony. Its resources may not bear comparison with those of some of its still richer neighbours; but, whatever those resources may be, they are certainly in course of development in a very intelligent and industrious manner. As soon as you reach Lake Alexandrina, patches of cultivation, comfortable homesteads, steam flour-mills, thriving townships, appear on all sides; and you feel that you are in a country which is being rapidly awakened to the eager wants of a civilized people.

I scarcely ever experienced so delightful a sensation as was produced by a view suddenly bursting on the sight, upon reaching the brow of a hill above the township of Willunga — a pretty little hamlet, about half-way between Goolwa and Adelaide. All day we had toiled on through a miserably barren country, with jaded horses and a wrecked vehicle, till both patience and temper had well nigh given way. The dreary gum scrub, the endless alternation of hill after hill, had been but feebly relieved by occasional fine prospects and the profusion of beautiful wild flowers, which in Australia usually appear to select the most uninviting soils for their homes. But just as the sun sank, the gloomy scrub seemed suddenly to melt away behind us, and a scene broke upon the view unlike anything I have ever seen since I left England. From the hill I speak of, a tract of country is visible for several miles in every direction — north, west, and south; and till it meets the sea, which fills up the background, it seems one continuous piece of cultivation. At a distance of thirty miles the haze of a large city indicates the site of Adelaide; and everywhere else the dappled sides of the gentle hills, the enclosures over miles upon miles of plain, the hedged gardens, the well-grown orchards, and well-appointed homesteads, proclaimed the possession of the land by an industrious and thrifty yeomanry.

The patches of green crop in luxuriant growth contrasted with the earlier cereals here and there yellowing for harvest: the dark soil — in one place fresh ploughed for a summer fallow, in another prettily dotted with the haycock — brought back in an instant all one's recollections of a great agricultural country. For nearly a score of years my eyes had never rested upon such a scene of continuous cultivation; it was the realization of a long-cherished dream. A good land system has thrown open the country freely to the people, and they have creditably, industriously, and intelligently availed themselves of it. It is England in miniature — England without its poverty, without its monstrous anomalies of individual wealth-extravagances. It is England — with a finer climate; with a virgin soil; with freedom from antiquated abuses; with more liberal institutions; with a happier people. And this is what I have always thought and hoped that Australia would become. It was in view of scenes like this that I first felt fully the pleasure of a realized day-dream.

The South Australian land system runs greatly upon eighty-acre sections. Surveys maybe claimed summarily all over the Colony, and the market is constantly kept supplied with eligible land at the upset price. Sections of eighty acres being the rule — a sort of established institution — you find the whole surface of the country divided into plots of this size. And a very good size, too! A labouring man knows that with the industrious application of a year or two he can save £80 and he concentrates his attention upon acquiring that suns.

|

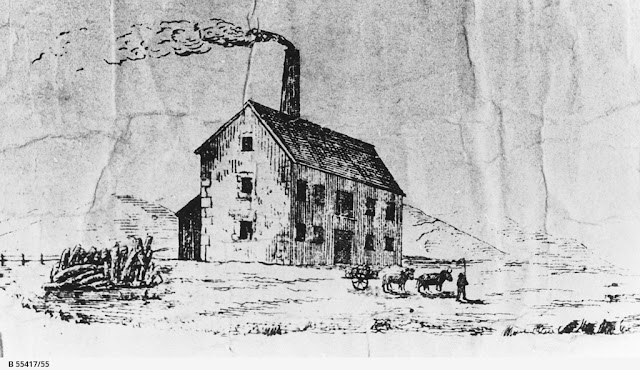

| Sketch from an early plan of the Willunga Flour Mill |

Meantime he is learning every day something to fit him for becoming a farmer in a new climate, and he is looking carefully for an eligible site for his future operations. After he has purchased his land, he perhaps has still to work on till he has procured the means of fencing it and purchasing a team of bullocks or a pair of horses. At last he is the proud possessor of a home of his own, and sturdily he buckles to his task of becoming an independent farmer. His first crop probably leaves him a comparatively rich man; his second enables him to buy another section or two adjoining his first; and thus, little by little, he becomes a thriving landowner and agriculturist; not so fast as to lead to intoxication at his position, and consequent mistakes — not so slowly as to dishearten him from effort, or to deaden his energies in any way. And it is by the multiplication of such men that South Australia is what she is, and that she is raising rapidly a race of industrious yeomen that I believe firmly will compare favourably with anything in the whole world.

Impelled by such influences, everything seems cheap and plentiful. The condition of the people is most gratifying, quite irrespective of money considerations.

Men may get rich less rapidly; but they are better, healthier, happier men. Life is better worth having, and the current of existence runs on in a more equable, natural, and wholesome stream. A great grain-producing people are not only well supplied with the most essential staff of life, but with all its kindred comforts and blessings. Plenty of wheat means plenty of hay, oats, and garden-stuff; plenty of fruit and vegetables; plenty of fowls, eggs, pork, butter, cheese, and milk.

Two things struck me forcibly in my progress through the country — the number of the flour-mills and the number of enclosures surrounded by well-grown hedges.

In one thing the people of Adelaide are setting a very good example, they are taking active steps in planting the city. Private persons are allowed, with proper restrictions, to plant along the kerb in front of their premises; and along all the terraces which surround the town, and in all the squares, which occur at frequent intervals, quick-growing and ornamental trees have been placed by the Corporation.

Upon one side Adelaide is sheltered by a range of hills, of which, considering their extreme beauty, I am surprised that I have heard so little. These hills are distant about five miles at the nearest point. The highest, Mount Lofty, appears 1,400 or 1,500 feet high, but is reported to be above 2,000. The tiers slope down into the plains, the entire way from the coast to the Burra Burra, a hundred miles up the country, presenting everywhere a beautiful appearance. Gently undulating — sometimes well covered with timber — sometimes open down broken up into all sorts of pretty forms, the eye never tires of resting on these delightful ranges. Here and there, in the richer and more sheltered situations, patches are broken up for cultivation, and little corners of intense green add variety to the landscape and show the all pervading industry of man.

The gardens in the neighbourhood of Adelaide exceed any that I have ever seen in the Colonies. They are very extensive, highly cultivated, and most productive. In due season, fruit abounds to such an extent that much of the more perishable kinds are lost altogether. The kinds range from the gooseberry to the loquat and the orange. Extensive olive gardens present themselves here and there, but, to my great surprise, no use whatever is made of the produce. The ground under the trees is actually black with fallen fruit; but the expense of preserving them, or of extracting the oil, is so great that it is found preferable to allow the abundant crops to perish altogether. A very experienced gardener on a large scale told me that he had offered to give anybody the whole crop if they could make use of it, but nobody had accepted the offer.

The vine is being very extensively cultivated, and with satisfactory results. Winemaking is progressing in numerous directions, and I have tasted several kinds quite up to the best average of New South Wales, and would pass muster amongst experienced wine-tasters in any country.

- Willunga: Sketch from an early plan of the Willunga Flour Mill which was later used for flax - Courtesy: State Library of South Australia [B 55417/55]

- Adelaide Almanack Town and Country Directory 1864 - Courtesy: State Library of South Australia

No comments