"The following admirable resume of the condition of the gold miners has recently reached us from the colony, and forms a fitting pendant to what we have already advanced relative to the locality of the mines. It is from a most trustworthy source, and will render our subject complete on all points which can interest the intending emigrant."

|

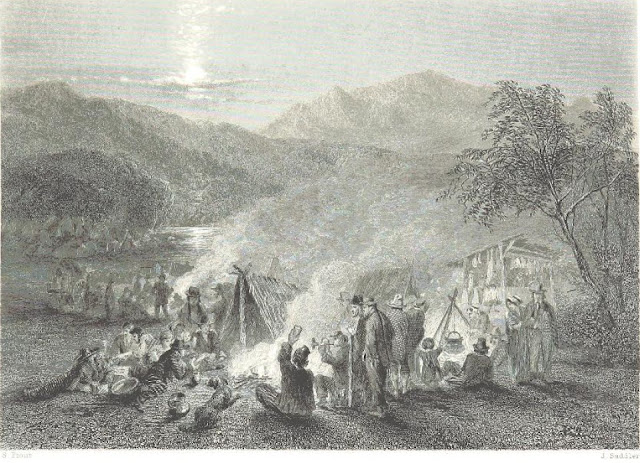

| Night Scene at the Diggings |

Turning from the locale of the diggings to the morale of the diggers, I can, from personal experience and without the least hesitation, affirm, that the tales of robbery and violence are very much distorted and magnified. When it is considered that a mass of some forty thousand souls is here assembled, very many of them coming fresh from an association with professed criminals, amongst whom robbery is a boast, and a deed of violence a recommendation, it is not at all surprising that some unlawful acts should be committed; but in a town population of like amount, guarded by a well-disciplined protective force, and avenged by a cunning detective, similar acts would be committed. At the diggings, moreover, I contend that, taking the amount of population, there is not a fourth part of the crime committed that there is in any town on the Australian continent; and yet there is, in the one case, the almost total absence of police protection and of household security; whilst, on the other, bricks and mortar, and solid doors, interpose between the thief and his plunder, and daily and nightly patrols are on the watch. In fact, I have often been astonished, in passing some of the stores, that the temptations to robbery which they offer have not more frequently been taken advantage of. I have remarked the sides of some stores composed of nothing more than a few gunny bags sewn so loosely together that between the interstices might be seen shirts of calico, woollen, and serge; trousers, belts, and all the other paraphernalia so dear to the digger's heart. These would require only one thrust of a knife to change ownership, whilst the thief need be under no dread of detection. As to the Lynch law, that exists only in name, no one instance having, in fact, occurred. Some few designing men have endeavoured, for their own purposes, to introduce this odious system under the more genial name of self-protection; but, thanks to the good sense, manly feeling, and true British spirit of the diggers, the proposition was scouted with all the contempt and loathing it deserved. Even the publicly-made assertion of one of the self-named leaders of the diggers, that 'the Government were prepared to wink at a certain amount of Lynch law,' did not in any way turn them from their honest purpose of appealing only to the law of the land, though the agents of that law were few amongst them, and though its proverbially strong arm was weakened by distance.

After much consideration and inquiry I have come to the conclusion that nearly the whole of this outcry of the insecurity of life and property at the diggings has originated with a few only — men of a low mental calibre, who, in ordinary and peaceable times, struggle in vain against insignificance, to which their want of sterling talent dooms them ; and whose only chance of rising into notoriety is, consequently, in the turmoil and disturbance of troublous times. To such as these it thus becomes an object to cause discontent, and to foment anarchy and discord, as, like the bubbles of noxious gas that rise to the surface of some pestilential pool only after strong agitation, these men, by their aptness at stringing together a few clap-trap phrases, manage thus to raise themselves to a position which they dignify by the name of a leader of the people. Some of these are acted on simply by a love of notoriety, but some few have a still deeper object. Penniless in purse, and almost without a standing in society, by thrusting themselves forward as the mouthpiece of the people, in delegations to the Government, to the officers of which they are as obsequious in the bureau as they are insolent in the face of a public meeting, a desperate game for place is played, in the hope their influence may be deemed valuable to meet the storm which they themselves have raised.

So far as I have seen of the diggings, the days are spent in toil and the night in rest, except only in the neighbourhood of some of the sly grog shops, in which scenes of drunkenness and debauchery may be sometimes witnessed. As the sun sets, the diggers retire from work, and the savoury smell from a thousand frying-pans indicate the kind of employment to which they next devote themselves. No sooner is the evening meal finished than some bugler strikes up some lively or well-known air, at the conclusion of which some rival performer advances his claims to superiority. At the conclusion of his essay, during which there has been the most profound silence, loud shouts of applause greet him from the tents around him, whilst those in the neighbourhood of his antagonist answer by mocking, by good-humoured cheers; joined by recommendations to 'lie down,' and 'shut up.' Anon the first bugler again commences, and instantly there is silence, and when he concludes his friends cheer, whilst the neighbours of his rival pass some playful commentary on his performance. In this way the rivalry is kept up for some time, till the buglers get tired and bid each other good-night, leaving the silence to be disturbed only by the barking of dogs, the neighing of horses, and the firing of guns.

One night we were amused by three players on the cornopean at different parts of the creek, who replied to each other, one selecting English, another Irish, and the third Scotch airs; I need not tell you what a beautiful effect this had, especially as after each air a volley was fired, almost with military precision, in the quarter whence the musician gave forth his sweet notes. Hore's brass band has latterly been playing for an hour or so every evening, and the shout that greeted, each time as it was concluded, must have rather astonished the knowing-looking old opossums in the gum trees on the ranges overhead. Did you ever see an opossum on a moonlight night sitting in the fork of an apple tree looking at you as you rode by? The gaze of amazement and curiosity which they give, is perfectly inimitable; and I often fancy what a rich treat it would be, if one could only catch a glance at three or four of the old men 'possums, squatting in solemn conclave on the gums above the creek, and mark the knowing, but inquiring look of the queer old customers, at the unusual scene below them.

Picture to yourself some forty thousand souls, for so many there must be, all resting under tents, the ends of which are triced up in hot weather to catch any passing breeze, many of them unguarded by a dog, and sleeping as sound as men who labour hard through the day always sleep, and then wonder, not that there are the few trifling depredations that we hear of, but that these are not far, very far, more. But, in truth, any person who keeps himself quiet and orderly, has little fear of being molested or disturbed; it is only those who, hankering after drink, resort to the sly grog shops, that are in danger of being robbed; and these, thrusting themselves into bad company, cannot expect aught else than to pay the penalty of it. To such as these, but small compassion can be extended; they know the danger they brave, as all are well acquainted with the fact that the lazy, the criminal, and the scheming make these tents their resort. This fact is well known to the authorities on the diggings, and too much credit cannot be given to the commissioners for the exertions they make to put down these sinks of iniquity. Hardly a day passes without at least one of these tents being burnt by the police, whilst some days witness two or three conflagrations.

When you come to consider the large number of men that the gold commissioner is called upon to overlook, and the very small constabulary force that is placed at his disposal, you will naturally think, with many others, that if he be active in his exertions, his whole time will be consumed in hunting up sly grog shops. As it is from these that springs the crime we have upon the diggings, it is naturally a first duty to keep a sharp eye upon them; and nothing but the most continuous activity could be of any avail to check an evil which, with the slightest negligence, would speedily swell itself to an extent that would destroy the last ruins that remain of the social fabric. But, in addition to his duty, the commissioner has the task of collecting the license fees; and to him the numerous disputes which arise amongst the diggers are referred for arbitration. Putting down the grog shops, and settling disputes, leave but small time for the collection of licenses, especially as a very large demand is made upon the commissioner's time by the returns he has to furnish to Government, and which he has to draw out himself.

Thus it is by no means extraordinary that only a very small proportion of diggers have paid the license fee; the only chance of calling the men to account being when settling a dispute at a water-hole, when those employed at the different cradles are called on for their licenses. With these they are of course provided, for the nonce. I have been at some considerable pains to learn the proportion which those who have taken out licenses bear to those who are working without them; and I really think, although you may perhaps deem my estimation out of all proportion, that not more than one-tenth of the diggers have paid the fee. Many have been up to the commissioner's tent to take out their license, and, after dancing attendance for two or three days, have been unable to get it, and have at length given up in despair all hope of obtaining it, and set to work without it. Finding themselves unmolested by commissioner or police, they have considered that the thirty shillings per month was as well in their pockets as in the coffers of the Government, especially as they got nothing in return, and thus they have continued to the present time. Others, more wide awake to the system, have saved themselves the waste of time of going to the commissioners, and have continued to work since their arrival without paying, but with an intention to pay whenever applied to. As to the commissioners visiting the holes, the thing is out of the question, as they are so scattered that a week would find but a very small portion of their charge visited; neither is it to be expected that the diggers should waste three or four days in every month in their endeavour to pay the tax. I hear that it is the intention of Government to remedy this part of the evil, by appointing an officer to be attached to each commissioner for the sole purpose of granting licenses. If this were the case, I feel convinced that the large majority of the diggers would readily pay the license fee, and would not even object to going for it, provided that no more than one day was to be lost to obtain it. When such an arrangement shall have been made, the man who refuses to pay will be set down as a schemer and an interloper, and to save his own reputation with those surrounding him, will be compelled to do as they have done before him.

With an increase in the amount received, we may naturally anticipate an increase in the police force of the diggings, and thus will be provided an additional means of discovering those who shirk the payment of the fee.

To give anything like an accurate guess at the daily amount of gold raised, would be absolutely impossible, for it is so variable that the return of one day is no guide whatever to that of another. Besides this, fully two-thirds of the diggers are unable to wash as they would do if there were plenty of water in the creek. Many of these are now employed at dry digging, or nuggetting as it is called here, in holes already sunk, saving, perhaps, a little of the choicest earth, which they bring home with them to wash in a tin dish, and setting aside the likely-looking stuff for the time when the cradle can be brought into operation. These are just making enough to clear themselves, with perhaps a trifle to spare, looking forward to the rainy season to pay them. Others, again, are prospecting, or sinking holes in the various gullies which give promise of gold; many of them have been eminently successful, and many localities have been discovered which will turn out a very large amount of gold when water shall be more plentiful. Thus all are in good heart, knowing well that, with the first fall of rain, a rich harvest awaits them. Even as it is now, every man may obtain a good day's wages if he chooses to stick hard to work, with of course the chance of falling upon a pocket if he should be in luck. Thus it is that the amount of gold procured still continues so large.

|

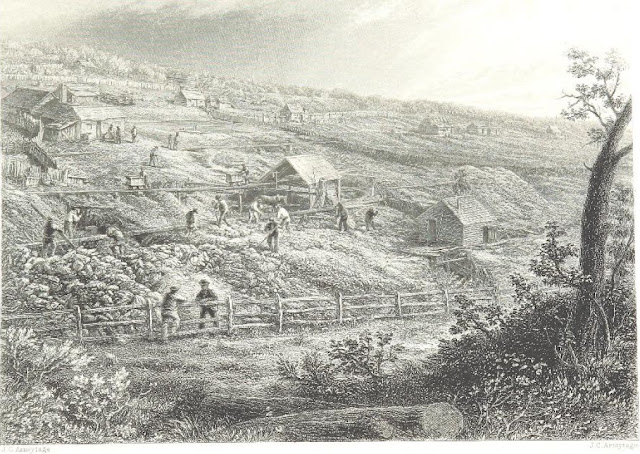

| Concordia Gold Mines Daylesford |

To give anything like an accurate guess at the daily amount of gold raised, would be absolutely impossible, for it is so variable that the return of one day is no guide whatever to that of another. Besides this, fully two-thirds of the diggers are unable to wash as they would do if there were plenty of water in the creek. Many of these are now employed at dry digging, or nuggetting as it is called here, in holes already sunk, saving, perhaps, a little of the choicest earth, which they bring home with them to wash in a tin dish, and setting aside the likely-looking stuff for the time when the cradle can be brought into operation. These are just making enough to clear themselves, with perhaps a trifle to spare, looking forward to the rainy season to pay them. Others, again, are prospecting, or sinking holes in the various gullies which give promise of gold; many of them have been eminently successful, and many localities have been discovered which will turn out a very large amount of gold when water shall be more plentiful. Thus all are in good heart, knowing well that, with the first fall of rain, a rich harvest awaits them. Even as it is now, every man may obtain a good day's wages if he chooses to stick hard to work, with of course the chance of falling upon a pocket if he should be in luck. Thus it is that the amount of gold procured still continues so large.

That large amounts still remain up at the mines, in the hands of individuals, is also certain, for many persons have a habit of planting their gold in some secure spot, gradually adding to their store, until it accumulates to such an amount as will enable them to follow the bent of their respective aspirations.

On these last two points I shall be able to give you some further information hereafter, after more extended inquiry, as I purpose returning to the diggings in a few days for a longer stay and a more comprehensive inquiry than I have yet made.

Coming now to the prices asked for provisions at the diggings, I find that a writer in the Argus has anticipated what I was myself about to remark. The charges are, on an average, about one hundred per cent, on Melbourne prices; the more necessary the article the greater the cost. This is owing almost entirely to the high rate of carriage; for, with roads in such a fearful state as our paternal Government leave them, the journey becomes a tedious and also a dangerous one and many of the carriers who have once been the road cannot be prevailed upon at any price to face it again. The bridges on the route are all insecure and dangerous to the last degree, that over the Coliban threatening to sink with every loaded team that passes over it; whilst many of the water-courses in heavy boggy soil will become impassable in winter. The diggers are now almost at a stand-still for want of rain but when it comes, I much fear that the road will in many places be impassable, and that the mines will have to be deserted from the impossibility of procuring supplies. All this has been known for some time — has been canvassed by the press, and talked over by the people— and yet our Government do nothing. Like Mr. James Macarthur, they adopt the motto, 'stare super antiquas vias;' and as long as an additional use of the whip can bring down the escort, and put 300/. or 400/. into the Government money-box, the executive will remain perfectly quiescent. I certainly do not like to join in the cry of a mob, and should feel rather inclined to take a lenient view of the acts of the Government, when I found that a general yell was set up against them, for this invariably looks like factious opposition. In the present instance, however, the mismanagement of what has been done, and the total neglect of what should have been done by the executive, is so glaring, so manifestly opposed to all that we have a right to expect from a good Government, that I should be acting the part of a traitor to the best interests of the colony did I attempt to lay the blame on the shoulders of any but those who deserved it. Hitherto the Government have incurred the responsibility only of having given the diggers dear food; in a few months the ghosts of famished hundreds will call for judgement upon them, whilst the execrations of ruined thousands will ring in their ears, and bid them to a fearful reckoning.

That the present amount of population at the diggings will be able to find food during the winter is admitted on all hands to be impossible, unless some improvement be made in the mode of transit; and even then it is doubtful if a sufficiency of carriage can be found. It will be then that we shall have to fear the social disorganisation that is now spoken of; it will be then that robbery and crime, goaded on by hunger, will stalk abroad; it will be then that the bowie-knifed and rifled Lynch will make his appearance; whilst our dozy executive will lie snugly ensconced behind the red- coated regiments of the mother-country, and look calmly on the anarchy that their torpid policy has educed.

Source: The Gold Colonies of Australia, and Gold Seeker's Manual, 1853, Publisher: Routledge, Contributor: Oxford University

No comments