"BANJO" PATERSON TELLS HIS OWN STORY. — PART 4

AN EXECUTION AND A

ROYAL PARDON.

Dramas of Yesterday.

HOW MORANT SHOT A PADRE.

BY A. B. ("BANJO") PATERSON.

Written in 1839.

WE ALL KNOW how Dreyfus was sentenced to life imprisonment on Devil's Island and how he was subsequently restored to citizenship; among other memories of mine is that of the convict Edmund Galley, who was sentenced to death for murder and afterwards pardoned and compensated. As it so happens, I knew Galley fairly well—as well as a young boy could be said to know an old "lifer," and so it may be worth while to relate his story from the Australian end.

I first met him when I was sent out in a spring cart to take his weekly rations. As the old song says:—

"Ten pounds of flour, ten pounds of meat,

some sugar, and some tea

Are all they give to a hungry man to last

till the seventh day."

Out I would go past the Bullock Hill and up Kuryong Creek, through unfenced country till I saw the bark roof and slab walls of Galley's hut. He was always on the lookout for the cart—all the shepherds except the mad ones were on the watch for the cart on ration day—and as soon as I hove in sight he would leave his sheep and come trotting down to the hut.

He was a little, hard, wiry Englishman, perhaps a provincial of some sort, though I have no recollection of his using any dialect. On my first visit he looked hard at me to see whether I could by any possibility be the man who committed the murder for which he had been sentenced to death. This was his obsession.

"Will you come in and have some tea? You're not afraid of me, are ye?" he asked.

I knew nothing about Galley except that he was a sent-out man—one of the "Old Hands"—so I said that I was not a bit afraid of him.

This seemed to indicate a lack of appreciation of his importance, so he came out with his story, all of a rush.

"I'm sent out for life," he said, "sent out for a murder I never done. There's lots would be afraid of me, I know the man that done it, though I never knew his right name, 'Twas a man they called the Kentish Hero. He got lagged for something else afterwards and he's out here somewhere now, and some day I'll find him."

Later on, I used to take Galley's rations to a new hut which he shared with a man named Howard, who had a wife and some half-dozen children. This mixed menage seemed to get along well and Galley must have welcomed the change from solitude; but, one day, there arrived at the homestead a rider on a sweating horse to say that Howard had been found dead at the foot of a tree with his skull crushed in and nothing to show how it happened.

Rumour ran rife round the scattered huts and homesteads that Galley and Howard had had a quarrel and that this was the result. By the time that the story had got a good start people had already invented the cause of the quarrel and added all sorts of picturesque details. The Yass police were called in; and, with Galley's record at his back, things might have gone hard with him, only that the police puzzled out the explanation.

Howard had been ringbarking a tree when he was killed. A large branch of dead timber was found lying alongside his body. Marks on the tree-trunk showed that this branch had been leaning against the tree and that the vibration caused by the ringbarking had made it slip off the tree-trunk, killing Howard with a glancing blow as it fell. Some of Howard's hair was found on the butt of the branch.

To try to upset a conviction in those days was like trying to take Gibraltar with a rowing boat, but there must have been a strong doubt as to the justice of Galley's original conviction. The "Exeter Times" (England) took up the case; members of Parliament brought up the matter in the House of Commons; and years after the conviction a request was made for testimonials as to his character in Australia. These were signed by my father, by Henry Brown, and by Walter Friend, a brother-in-law of Henry Brown. All were magistrates of the colony, and Walter Friend and Henry Brown were wealthy and influential men.

Walter Friend was a hard-headed business man. His name carried weight, and after the testimonials arrived the Law in England admitted that it had made a mistake, and issued a Royal pardon to Galley in 1879. The authorities also awarded Galley the sum of a thousand pounds as compensation for the wrong done him and of this compensation money my father was made trustee, to administer it at his discretion for Galley's benefit.

Handsome Adventurer.

My bush upbringing had made me tolerant of the battlers of this world, for, but for the grace of God, I might have been one myself. Here is a story of a celebrity with whose career I managed to get mixed up.

In my mail one morning I found a letter from an uncle of mine, a hard-headed grazier who had been through the mill; who had been broke and had made a fortune; and who had accumulated a great knowledge of the ways of the world.

He wrote: "There is a man going down from here to Sydney, and he says he is going to call on you. His name is Morant. He says he is the son of an English Admiral, and he has good manners, and education. He can do anything better than most people; can write verses; break in horses; trap dingoes, yard scrub cattle; dance, run, fight, drink, and borrow money; anything except work. I don't know what is the matter with the chap. He seems to be brimming over with flashness, for he will do any dare-devil thing so long as there is a crowd to watch him. He jumped a horse over a stiff three-rail fence one dark night by the light of two matches which he had placed on the posts!"

That same afternoon a bronzed, clean-shaven man of about thirty, well set up, with the quick walk of a man used to getting on young horses, clear, confident eyes, radiating health and vitality, walked into the office and introduced himself as Morant.

"I've been stopping with your uncle, Arthur Harton," he said, "and when he heard I was coming to Sydney he told me to be sure and call on you. Fine man isn't he? He knows me well. He said if anybody could show me round Sydney you could."

This set things going, so to speak, and the talk drifted from stag-hunting on Exmoor to galloping up alongside wild cattle and ripping them with a knife, in the scrubs at the back of Dubbo, which, in those days, was quite far-out country. We had a hunt club in Sydney in those days, and he said that he must get a horse and come out with us. He talked like a man without a care in the world. I found myself comparing him with the picturesque heroes of the past who fought for their own hand. Nowadays we would call him a case for a psychologist. Yet, he was no Micawber; he did not wait for something to turn up; he tried to turn it up for himself.

|

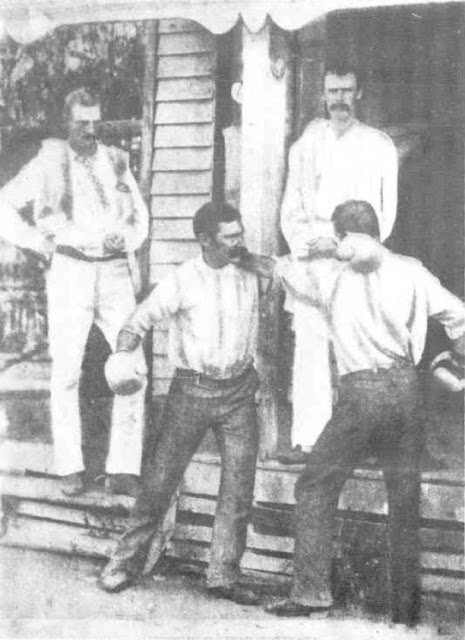

| "Breaker" Morant and a Friend Boxing Somewhere Back of Bourke - date unknown |

This set things going, so to speak, and the talk drifted from stag-hunting on Exmoor to galloping up alongside wild cattle and ripping them with a knife, in the scrubs at the back of Dubbo, which, in those days, was quite far-out country. We had a hunt club in Sydney in those days, and he said that he must get a horse and come out with us. He talked like a man without a care in the world. I found myself comparing him with the picturesque heroes of the past who fought for their own hand. Nowadays we would call him a case for a psychologist. Yet, he was no Micawber; he did not wait for something to turn up; he tried to turn it up for himself.

Time passed on golden wings while we were chatting about the bush, and it was just on three o'clock when he hurriedly looked at his watch. "By Jove," he said, "I've enjoyed myself so much talking to you that I forgot I had to cash a cheque. And now the banks will be shut. Perhaps you could cash a cheque for me for a fiver. I've got to pay some bills and I've run myself clean out of money."

Almost unwillingly I said that I did not have it about me, and suggested that he should let his creditors wait till the banks opened in the morning. He dismissed the matter with a wave of his hand, and neither then nor at any other time did he bear any malice for the refusal.

His reputation as a daring rider, and his relationship to an admiral, made him a social lion. Asked to stay with some of our best people, he turned up riding a pony, with his luggage on the saddle in front of him. This was a great act, and went over big. He got them to take in the pony for him and borrowed some clothes from the son of the house who happened to be about his own size. Then a charity gymkhana was organised, and a buckjumper was wanted to give tone to the proceedings. Who could provide a buckjumper so well as Mr. Morant? He fairly lived on buckjumpers away back in his own wilds. He borrowed ten pounds from the gymkhana committee to pay the expenses of the buckjumper, a celebrated grey animal which he meant to bring down from Dubbo by rail. This also went over big, and people flocked to the gymkhana to see the celebrated Morant's celebrated buckjumper.

Unfortunately the man who owned the buckjumper knew Morant quite well; and while he was unwilling to lend his animal to anybody, his unwillingness to lend it to Morant amounted to an obsession. Did this disconcert our hero? Not a bit of it. He went out to the saleyards and agreed with a dealer who bought horses by the carload to break in for him a grey horse, one of a truckload; and this horse (as it turned out) knew no more about buckjumping than it knew about the Einstein theory. The animal's performance at the gymkhana was such a "flop" that the committee squealed like anything about their ten pounds, and said that they were going to stick to the grey horse until they got their money back. A fair enough proposition, until the owner of the so-called buckjumper turned up and offered to give the secretary of the gymkhana a lift under the ear if he did not give the animal back.

Unfortunately the man who owned the buckjumper knew Morant quite well; and while he was unwilling to lend his animal to anybody, his unwillingness to lend it to Morant amounted to an obsession. Did this disconcert our hero? Not a bit of it. He went out to the saleyards and agreed with a dealer who bought horses by the carload to break in for him a grey horse, one of a truckload; and this horse (as it turned out) knew no more about buckjumping than it knew about the Einstein theory. The animal's performance at the gymkhana was such a "flop" that the committee squealed like anything about their ten pounds, and said that they were going to stick to the grey horse until they got their money back. A fair enough proposition, until the owner of the so-called buckjumper turned up and offered to give the secretary of the gymkhana a lift under the ear if he did not give the animal back.

After this, our hero's reception at his temporary home was anything but enthusiastic, but, with his queer flair for theatricalism, he managed to make an exit with a certain amount of glory. He said that he was called away suddenly to Queensland, to inspect a station, and as they had treated him so well he wished to present the son of the house with the pony which would be of no further use to him. He would take no denial, and he handed over the pony with a sort of Arab's farewell to his steed—a touching scene which lingered in their memories till the owner of the pony cast up and took it away, saying that he had paid Morant a couple of pounds to quieten it for a little girl!

Such was the man who was shot by the British Army after a court-martial for defying Army orders and shooting a prisoner in revenge for the death of one of his best friends. I happened to know all that was to be known about Morant's trial and execution, for the lawyer who defended him, one J. F. Thomas, of Tenterfield, asked me to publish all the papers—evidence, cablegrams, decision, appeal, etc.,—a bulky bundle which he carried about with him, grieving over the matter till it seriously affected his mind. He blamed himself, in a measure, for the death of Morant, but I could not see that he had failed to do the best he could with a very unpleasant business.

Execution of Morant.

This was the story of the Morant affair, told me by Thomas, and confirmed by reference to his bundle of papers:—

"Morant," he said, "was detached from his own command in South Africa, and was acting under the orders of a civilian official named Taylor, who knew the country and had been appointed by the Army to go round the out-lying farms requisitioning cattle. They knew that Morant was a good hand with cattle, so that was how he was put on the job. He had a few men under him, and pretty well a free hand in anything he did. They had to keep their eyes open, for wandering bands of the enemy used sometimes to have a shot at them, and in one of these skirmishes a mate of Morant was killed.

"Morant told me," said Thomas, "that he had orders not to let all and sundry wander about the country without proper permits. He questioned a man who was driving across country in a Cape cart on some business or other. According to Morant, he thought that this man was acting as a spy. It so happened that Morant had just seen the body of his mate and claimed that it had been disfigured; that somebody had trodden on the face. Of course, everybody was excited, not knowing when there might be another skirmish. Morant told his men that he had orders to shoot anybody in reprisal for a murder or for disfiguring the dead for for spying. So he took this man out of his Cape cart and shot him! Unfortunately, the victim turned out to be a Dutch padre."

Somehow, I seemed to see the whole thing — the little group of anxious-faced men, the half-comprehending Dutchman standing by, and Morant, drunk with his one day of power. For years he had shifted and battled and contrived; had been always the under-dog, and now he was up in the stirrups. It went to his head like wine.

"Morant was sentenced to death," Thomas said, "but I never believed the execution would be carried out. When I found that the thing was serious I pulled every string I could; got permission to wire to Australia, and asked for the case to be reopened so that I might put in a proper defence. It was of no use. Morant had to go. He died game. But I wake up in the night now, feeling that Morant must have believed that he had some authority for what he did and that I ought to have been able to convince the Court of it."

Poor Thomas! He died years ago, and has taken his troubles to a Higher Tribunal.

[Note.—Mr. F. M. Cutlack writes: One takes a man as he finds him in this life, especially in the bush, but as one who know Harry Harbord Morant well and affectionately—adventurer as he was—I deplore that "Banjo" Paterson does not even remember his universally known nickname of "The Breaker," the name with which for years he signed his verses in "The Bulletin." Perhaps he deceived some people, and left them angry, but he was known in all the back country from Queensland to the Lower Murray, and great numbers of other people of careless habits—or even of some scrupulous rectitude—loved him despite his faults. A great cry of protest went up when he was shot—reprieved too late we heard, by Kitchener—and when I last saw it, in 1913, his grave was the greenest in Pretoria Cemetery, and so kept by an Australian committee. His Boer War story is told in "Scapegoats of Empire," by Lieutenant Witton, one of those court-martialled with him, and also in a smaller volume, "Bush-veldt and Buccaneer," written under a pen-name by Frank Fox, then of the "Bulletin" staff.]

[This series of articles will conclude, in Part 5, when Mr. Paterson writes of some of the political "giants"of pre-Federation days and of a romantic attempt to colonise the New Hebrides.]

Sources:

- "BANJO" PATERSON TELLS HIS OWN STORY.—IV. AN EXECUTION AND A ROYAL PARDON. (1939, February 25). The Sydney Morning Herald (NSW : 1842 - 1954), p. 21.

- Andrew Barton (Banjo) Paterson c. 1890; Courtesy: Mitchell Library, State Library of New South Wales

- Pictures of Breaker Morant: The Murder of Boers. (1902, April 12). The Sydney Mail and New South Wales Advertiser (NSW : 1871 - 1912), p. 929.

No comments